Ban Bara Ban: Inside the Sound Experiments of Chumei Watanabe

Exploring the sound behind Japan’s robots, heroes, villains—and the man who made them unforgettable.

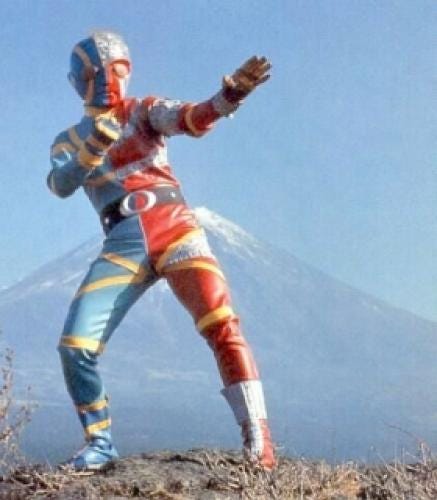

By the early 1970s, television in Japan had become a daily ritual. Kids raced home from school, turned on the set, and entered parallel worlds of masked heroes, transforming robots, and intergalactic battles. The visuals were vivid—but it was the music that gave the stories gravity. Behind many of these themes, from Mazinger Z to Gorenger to Space Sheriff Gavan, was Chumei Watanabe, whose work became etched into the collective memory of a generation.

Watanabe had already been working in music for two decades by then. He got his start in 1953 writing for radio dramas, often working with limited instrumentation but unlimited curiosity. As the postwar media landscape evolved, he moved from radio to film and then to television, gradually developing a distinct musical identity—one rooted in experimentation, immediacy, and an instinctive understanding of what makes a moment stick.

If you grew up in Japan in the ’70s or ’80s, you grew up with his sound. His themes didn’t just underscore the action—they were part of the action.

The Self-Taught Prodigy

In sixth grade, a classmate’s harmonica playing piqued Watanabe’s curiosity, and he began a journey of self-education. His father, skeptical of music as a career, insisted: “A composer needs more than a harmonica—you need to learn the piano.” Luckily, his sister’s unused piano was at home, and Watanabe took to it instinctively, teaching himself to read music without formal lessons.

His real education, however, came from NHK’s 6pm radio program Meikyoku Kanshō (Masterpiece Appreciation). While his peers listened to pop tunes, Watanabe absorbed Beethoven’s Eroica and Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique Symphony, laying a foundation he would twist and subvert later in life.

At Tokyo University, he studied psychology with a focus on psychoacoustics—the science of how humans perceive sound. His thesis was highly regarded, and he was encouraged to pursue graduate studies. But when his father fell terminally ill, Watanabe left academia to care for him. After his passing, something shifted. Watanabe did something no guidance counsellor would have suggested: he walked into the local broadcasting station and said, “I want to be a composer.” Somehow, that worked and eventually they handed him manuscripts. It was 1953.

The Jazz Awakening & A Leap to Tokyo

Postwar Japan was flooded with American culture, and jazz arrived in full force. Watanabe first encountered it in local movie theatres and on Armed Forces Radio—Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, big band swing. He listened with classical ears and absorbed it like code.

In Tokyo, he studied under Ikuma Dan (composer of the 1964 Olympics ceremony music) and Saburō Moroi. His most transformative influence came from saxophonist Sadao Watanabe, who had returned from Berklee College of Music with a new language of harmony and form. Under his guidance, Chumei absorbed the Berklee system and Schillinger theories, developing a fluidity between jazz improvisation and cinematic structure.

Settling in Asagaya, he lived in a one-room apartment with no running water, relying on a shared well. He began composing for radio dramas before breaking into film. Then came the opportunity that changed everything: Jinzō Ningen Kikaider and Mazinger Z, both in 1972.

A Sound That Defined an Era

Watanabe had no interest in writing polite music. The early ’70s demanded something sharper, stranger—sounds that could carry exploding robots and masked crusaders into the living rooms of millions.

His classmate and ethnomusicologist Fumio Koizumi (who later mentored Shoji Yamashiro of Geinoh Yamashirogumi) introduced Watanabe to the Rokuchō scale, a minor pentatonic found in Japanese folk and African-American blues. This became a core part of his sound, paired with electric guitar, tight brass, and punchy rhythms.

His signature techniques included:

Scat Vocals: Percussive nonsense syllables like “Ban Bara Ban Ban Ban!” and “Dan Da Da Da Dan” that mimicked the physicality of battle and transformation sequences.

Experimental Sound Design: Bowed vibraphones, timpani with rubber balls, suspended nails used as chimes—anything to push the sonic frame.

Funk & Big Band Horns: Drawing inspiration from Jerry Hey and jazz-fusion charts, his arrangements brought syncopated grooves to action scores.

The Mystery Song: Shigi Shigi

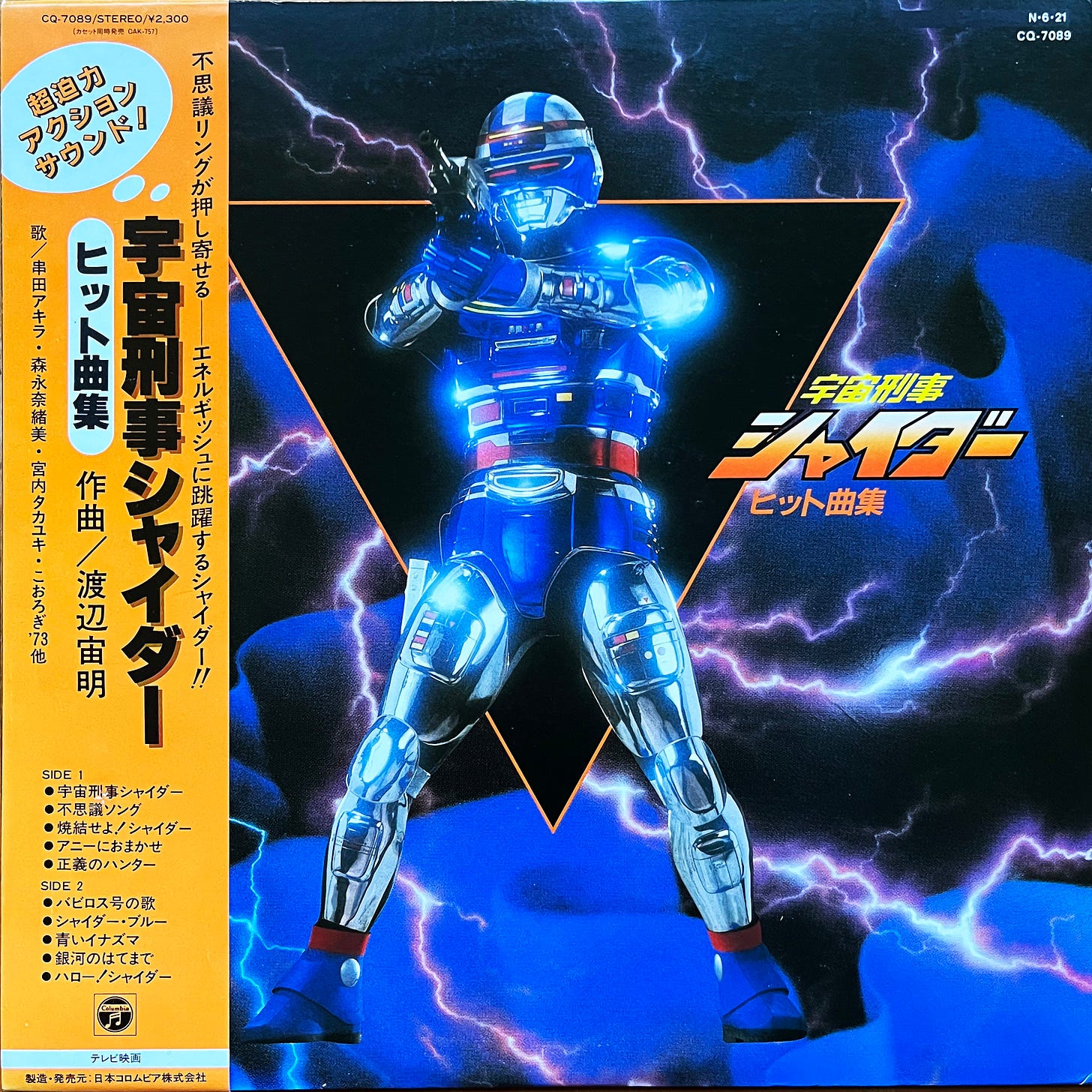

Included in TV, Anime & Manga New Age Soundtracks 1984–1993 is a lesser-known Watanabe track: Fushigi Song, written for Uchuu Keiji Shaider (1984), the third Space Sheriff series. In the show, the villains use this eerie track—“Shigi shigi, shigi shigi…”—to hypnotise Earthlings and trap them in dreamlike states.

The piece is stripped and surreal: choral repetition, icy synths, and near-silent percussion. It’s not heroic. It’s disorienting. And that’s what makes it unforgettable.

Watanabe often said each scene was a new universe. Fushigi Song proves he could bend tone and mood as easily as he bent melody.

DJ MURO & the Hip-Hop Connection

In 2016, DJ MURO interviewed Watanabe and likened his work to hip-hop. Not because of direct lineage, but because of how his arrangements felt looped, layered, and sample-ready.

Watanabe worked like a beatmaker before the tools existed. His chopped vocal phrases, skewed timings, and deep low-end made his work a digger’s dream. MURO called it “very hip-hop in its experimental nature.”

Everything into the Machine

By the 1980s, Watanabe embraced synths and disco-funk textures. Shows like Denshi Sentai Denziman and Taiyō Sentai Sun Vulcan featured four-on-the-floor rhythms under horn blasts and slap bass lines.

Then came Uchuu Keiji Gavan (1982). A bluesy anthem stitched with electronic swagger. He called it his masterpiece: “The lyrics and melody are one. It captures the spirit of the hero completely.”

It’s all there—jazz, funk, folk, disco, TV theatre—folded into a theme song that still slaps.

Transmission Beyond Borders

Watanabe’s music made unexpected leaps across borders. Steel Jeeg was huge in Italy. One of his pieces ended up in a French car commercial. Collectors and DJs continue to rediscover his catalogue, drawn to its grit and imagination.

The track in TV, Anime & Manga New Age Soundtracks 1984–1993 isn’t one of his greatest hits—but it carries his spirit: fearless, melodic, and slightly unhinged in the best possible way.

Watanabe never joined a talent agency. He didn’t chase trends. He stayed independent, experimental, and prolific. What he left behind isn’t a genre. It’s a universe. One that still sounds like it belongs to tomorrow.

Purchase TV, Anime & Manga New Age Soundtracks here

💡 Paid subscribers perk:

April’s discount code for Bandcamp is just below—thank you for supporting what we do.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Time Capsule to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.