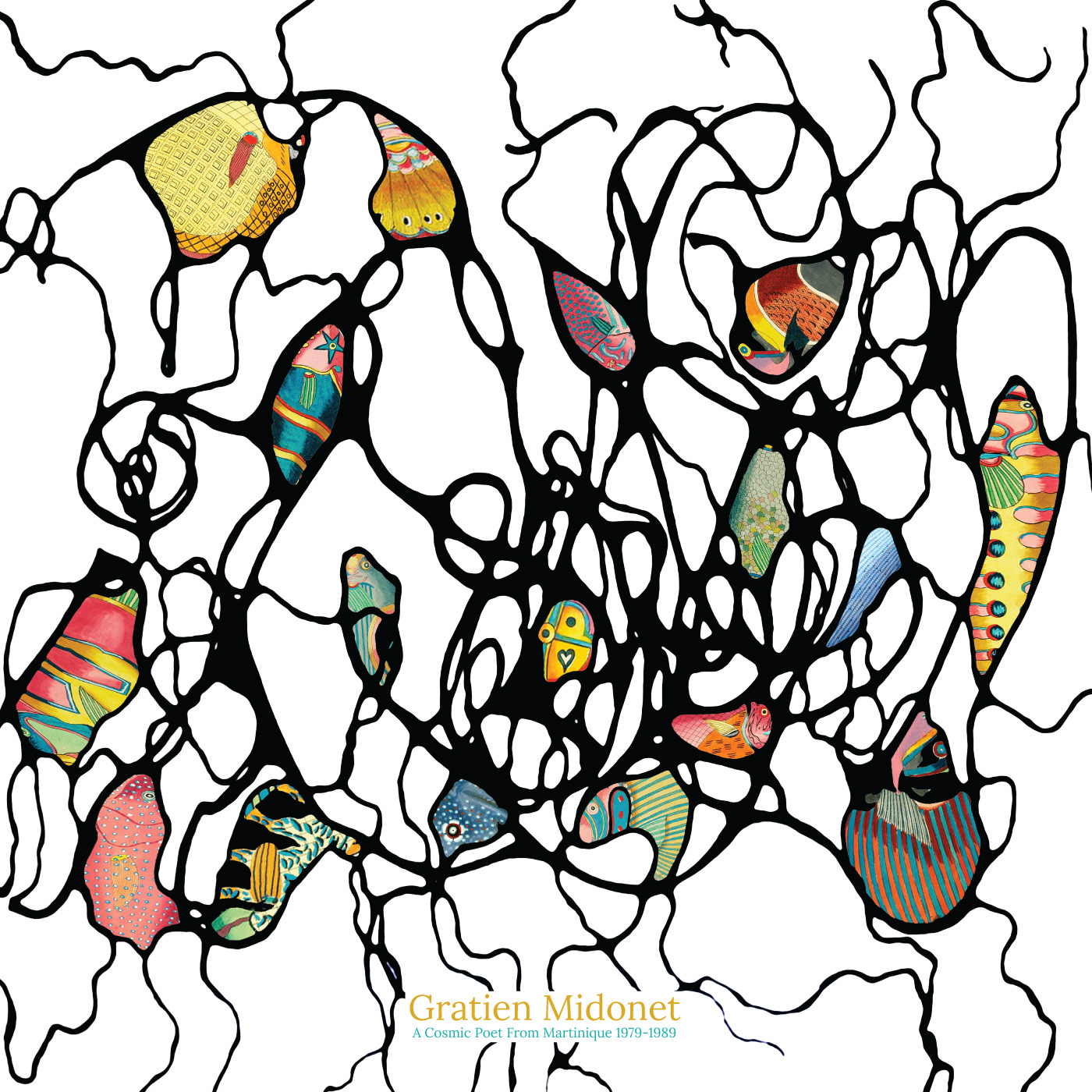

Gratien Midonet: A Cosmic Poet From Martinique

From Martinique to New Caledonia, tracing the mystical, poetic, genre-defying journey of a visionary artist. Written by Cedric Lassonde (Beauty & The Beat)

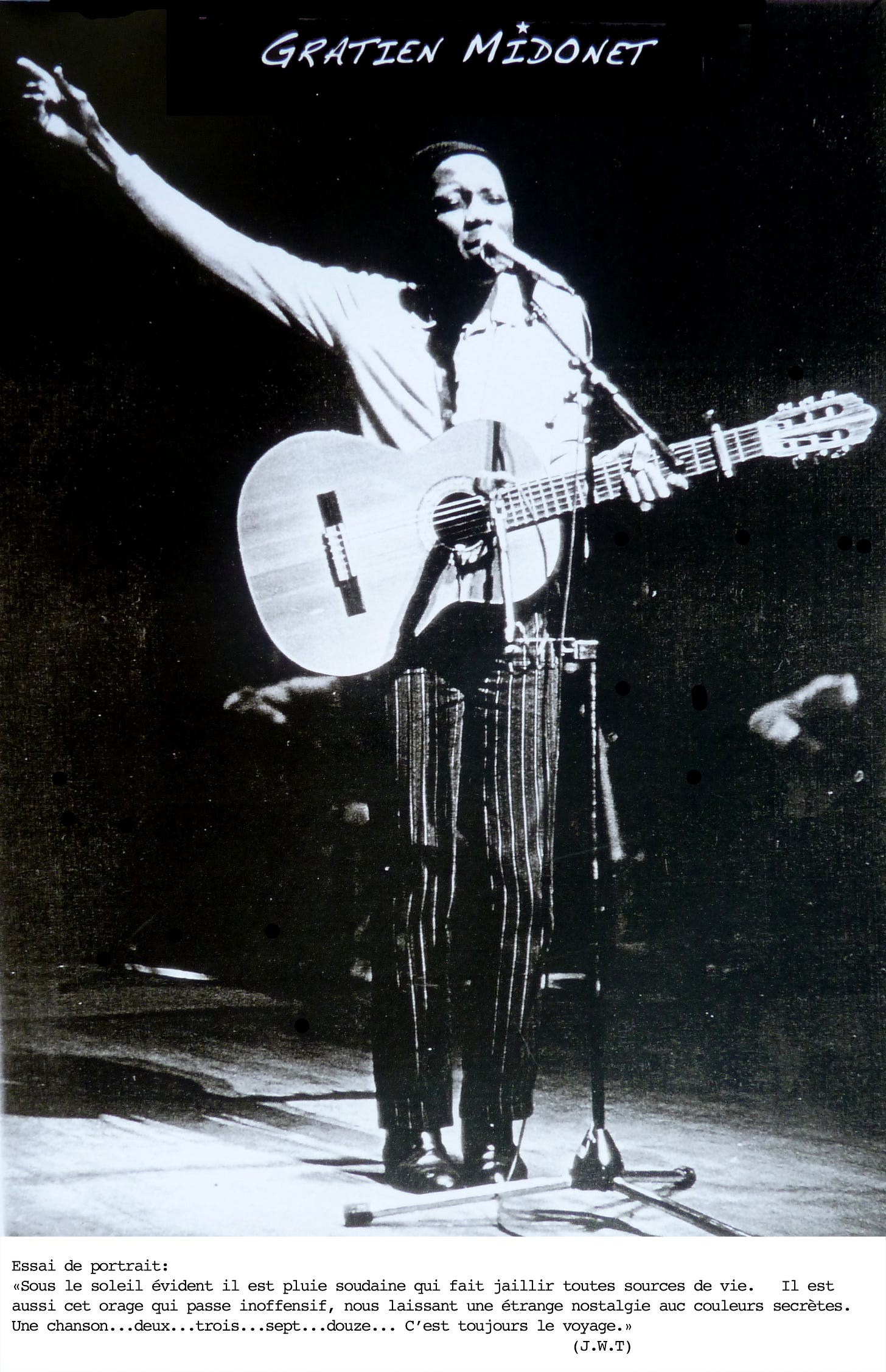

The first time I was introduced to Midonet’s music was at Beauty & the Beat a few years ago when our guest Pol Valls closed the party with a trademark set of cosmic delights from all corners, a set which included 'Mari Rhont Ouve La Pot’. Just put the track on and imagine the effect of such a bomb being dropped - through Klipschorns - at 5am, to a room filled with the most psychedelically inclined tropical ravers in town…The unusual fusion of heavy Afro-Caribbean drumming and spaced out synths sounded devastating on the dance-floor, so unique. So BATB!

I did the obligatory run to the booth, got the ID, recognised the label (Touloulou out of Martinique, home to fellow visionaries Luc-Hubert Séjor and Eric Arconte) and started digging deep into the man’s discography. To my surprise Midonet seemed to have slipped under today’s radar despite owning such a unique, idiosyncratic style and a body of work comprising six full length albums alongside numerous poems and short stories. A couple of years down the line, I tracked him down in…New Caledonia (of all places), and slowly but surely the mystery started to unfold as we pieced together the puzzle of his life.

Decolonization Without Independence

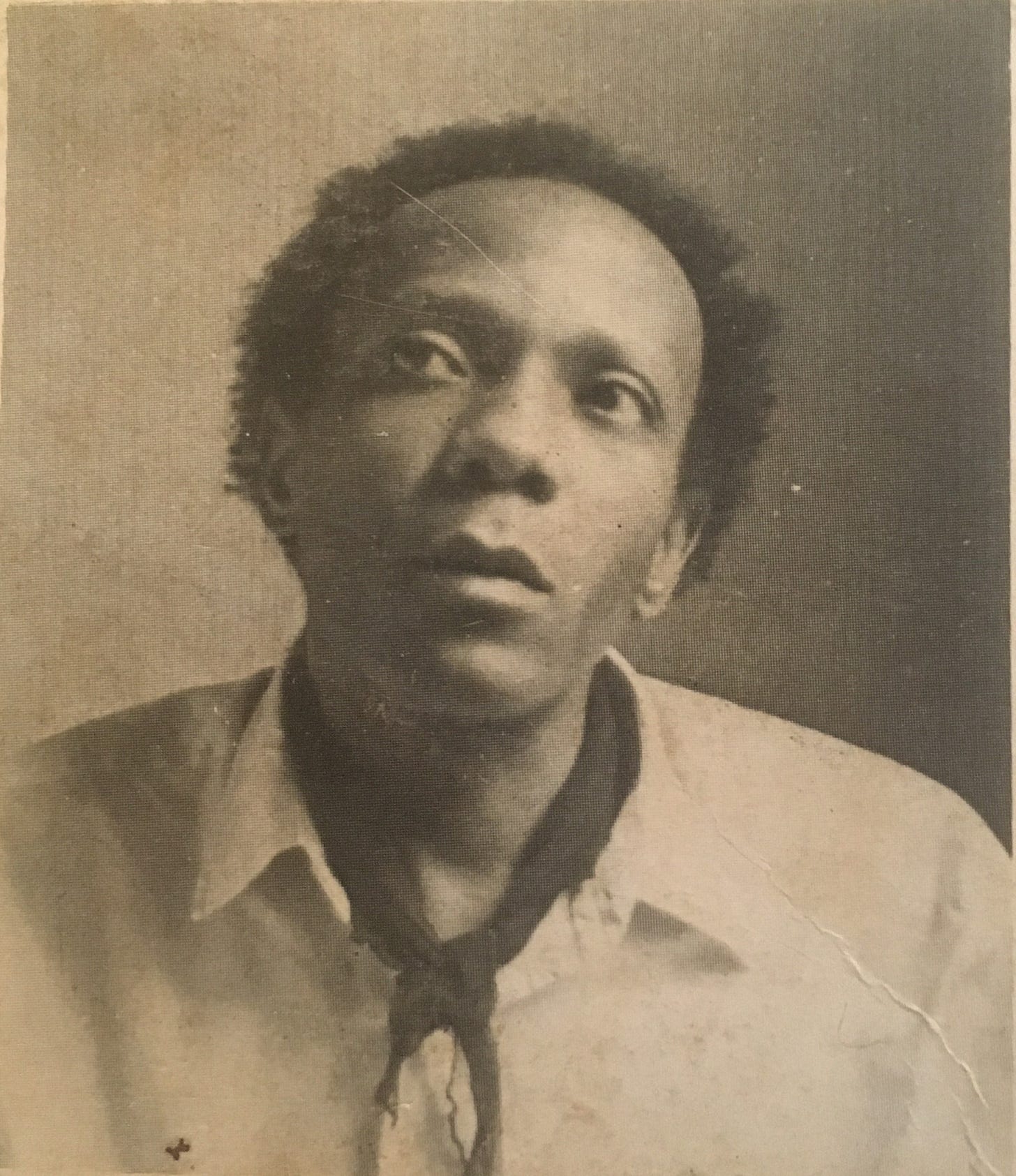

Midonet was born in 1944 in the “La Folie” neighbourhood of Fort de France, capital of the Caribbean island of Martinique, just as the island and its people were about to start the process of an unprecedented form of decolonisation.

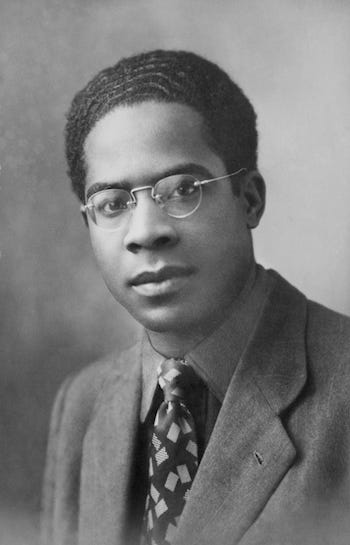

In 1946, nearly a century after the (re-)abolition of slavery by France (22nd of May 1848), Martinique had obtained, at the urging of the then young communist deputy mayor Aimé Césaire, the status of an overseas départment of the French state. It meant decolonisation without national independence, a vision shared by Césaire, from colonial Martinique, together with Léopold Senghor, from colonial Senegal, later to become the country’s first president (the pair met as students in Paris). Their Négritude movement, which aimed to unify and symbolically bring together black people all over the world (influenced by pan-Africanism) , drove Martinique to become one of the few postcolonial societies (alongside neighbouring Guadeloupe) to integrate with their colonial states instead of pursuing independence.

As well as Marxist political philosophy, in the Black radical tradition, Césaire and Senghor drew heavily on surrealist literary style, and in their work often explored the experience of diasporic being (see Césaire’s poem 'Notebook of a Return to My Native Land’).

From La Folie to the ‘Colombie’

Midonet, whose mother was the unacknowledged daughter of a white solicitor from Guadeloupe (a fact she kept hidden from her children for the longest time), would as a diasporic being himself, grow up to become a great admirer of Aimé Césaire’s oeuvre, both in the political and the literary fields.

Having left his island as a young teenager to pursue studies in mainland France, he explains how this abrupt departure and the subsequent voyage left a profound and long lasting mark on the young man’s creative motivations. He remembers the journey, on board the ship ‘Colombie’, as an experience of being “confined several days between sky and sea, the blue tinted heroics of the flying fishes, and the psychic ti-bwa of the few passengers who had known the chouval-bwa”.

Drums, Spirits & Soul States

The chouval bwa mentioned by Midonet is the name of a traditional folk music which mixes bélè drumming with melodic instruments like flute or accordion, but it also describes a hand-powered wooden carousel with musicians playing at the centre.

Bélè, which was Martinique’s most important style of music before the advent of beguine and zouk, is based heavily on the drums and deeply rooted in Afro-Caribbean musical influences traced back to the slave trade. Tanbouyé masters (drummers) sit on a large tambour (also called bélè), effectively riding like a horse (‘cheval’) the beats that they improvise; a singer metes out call and response chants in Creole, while the rhythm is being kept by the tibwa, two wooden sticks striking either a piece of bamboo or the back of a tambour. The term chouval bwa also describes a hand-powered wooden carousel with musicians playing at the centre.

The ti bwa (Creole for ‘petit bois’ in French), much like the ka or gwoka in Guadeloupe (the tambour at the heart of gwoka music), has gradually been used to evoke a much more abstract and spiritual dimension, describing ‘un état d’esprit’, a mystical state of mind shared by the people of Martinique. Midonet talks about ti bwa as being “the soul of Martinican music” and recorded at least 2 versions of a song simply called ‘Ti Bwa’.

Midonet’s first musical recollections are of the beguines “d’antan" (‘of old’) sung by his father, then a tenor in a choir. After randomly winning a guitar at a local fair he started teaching himself how to play the instrument, to write and compose. However, he would never consider himself a ‘proper’ musician, and after his arrival in Paris in the early 1960s, it would take him the best part of two decades to start releasing music.

The Philosopher Who Carved Wood and Channeled Songs

After studying philosophy at university and many a wandering, he obtained a degree in psychopedagogy (a combination of pedagogy and psychology) and worked as an educator in an institute for the highly gifted for a decade. He was notably in charge of the wood carving workshop (an art form he still practices today), and has fond memories of working with these teenagers with high IQs but who were often inept socially or within their families, likening these interactions to an auto-psychoanalysis.

During this time he was writing songs and had started to meet the musicians that would accompany him on his future albums. They all embraced the fact that Midonet wasn’t a classically trained musician, and were excited to follow him and play it by ear.

Midonet’s main source of inspiration was a sentiment of pure nostalgia for his island,

“where everything was mixed up, its smells and colours, its subliminal noises, its fruity notes, the memories of funeral wakes, the bombastic organ of the cathedral and the gasps of the drums”

(during these funeral wakes in the Caribbeans, drums are traditionally being played, bélè in Martinique, ka in Guadeloupe), without him knowing the nuanced differences between gwoka and bélè.

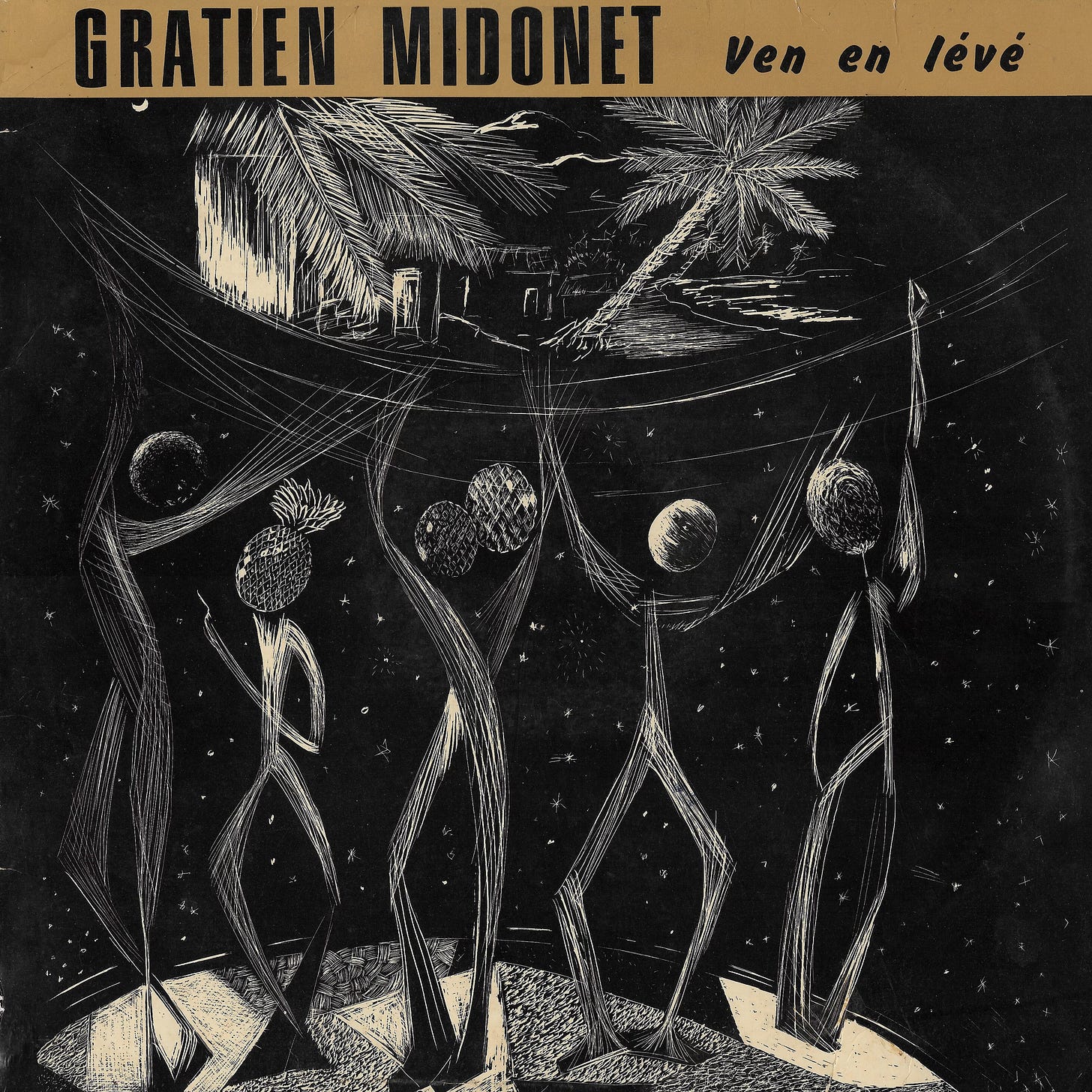

Nevertheless he remembers the conception of his first album ‘Ven En Lévè’ as being very fluid: the melodies, the words, the influences all coming naturally.

Music as Movement, Music as Message.

Midonet had written the song ‘Ven En Lévé’ (‘A Rising Wind') two years before resigning from his day job, and it became an instant hit upon its release in 1979. It was massive in Martinique and amongst the French Caribbean diaspora, and an anthem for the then popular independence movement. It was used as such during the trial of one of their activists at the time and subsequently banned for two years from the French airwaves, which consequently made the song even more popular, as it would be covered in 1981 by Les Vikings de la Guadeloupe (later to become Kassav) and still is to this day by the likes of Akiyo (a popular pro-independence carnival drum band from Guadeloupe). ‘Ven En Levé’ and some of his texts are still being studied in schools in Martinique and Guadeloupe today.

Midonet says the lyrics came to him as in a dream, that he was a mere “channel”, a messenger transmitting what came to him subconsciously. This brings us to an essential aspect of Midonet’s personality.

Animism, Extraterrestrials & Universal Laws

A lot of his time during those years was spent on a quest for self-development and he talks openly about being recruited by the “Mystery Schools”, about having to deal with witchcraft, extra-terrestrial encounters in the subway…He has been an animist for many years: he talks about “seeing the divine in all natural things, the bird that flies, the tree that quivers”, a feeling or more precisely an experience he links to pan-Africanism through primitive arts and African sculptures. He insists that this is what he sings about.

One of his mottos is “to not identify oneself with the external and artificial Matrix but to keep track, in all conscience, of the unsurpassable universal laws of Nature…”

This explains why Gratien never thought of his career in a professional way. True to his mystical beliefs he neglected all wealth and worldly possessions and he talks about these privations as being “necessary to reach the transcendental worlds whose door remains closed for most humans”. This might sound a bit far out for most of us but in the context of Midonet’s music it makes a lot of sense. Midonet’s musical world is cosmic, mystical and he has created his own idiosyncratic style around it: not plain folk, not bélè, chouval bwa, beguine or gwoka, but rather a transcendental fusion of all these and a true reflection of his personality.

One concept which came up early on in our discussions, and which gives a good insight into Midonet’s psyche, was the constant search in his creations for what he calls ‘the spirit of transes-mystiques’:

“The drums which tumble from the cliff, shaking, only to levitate once again at the call of a Tibetan bowl or a crystal clear xylophone…A meditative repetition, akin to a deep breathe which soothes the overflowing wanton thoughts, this is what accounts for the nature of the future world mutations…To be suddenly conscious of the new dimensions, to be Gratitude…not in the mental neo-cortex, but rather to be Joy, Lightness, Love and Wonders in the right brain.”

Creole, Créolité & the Word Made Sound

Gratien is first and foremost a poet-singer, a man who loves words and whose aim and dedication was always to write and sing in Creole to express the beauty and poetry of his native language (though not exclusively as he would often switch between Creole and French to suit a particular text or song).

His inspirations are to be found in the field of literature rather than music, and although he wasn’t especially political (at a time when the Martinican Independence movement was very strong), he cites as notable influences the cult Martinican writers and essayists Aimé Césaire (“all of it”), Edouard Glissant, the father of the concept of tout-monde (a view of the whole world as a network of interacting communities whose contacts result in constantly changing cultural formations), as well as Patrick Chamoiseau, who won the prix Goncourt in 1992 for Texaco, a book (much loved by Midonet) whose central theme is the use of Creole language as a way to express the heroine’s struggles to negotiate the worlds of French and Creole, the classic and the patois, the colonizer and the colonized.

Though Chamoiseau is a contemporary of Midonet, and as such wasn’t a direct influence, they both are militant proponents of the use of the Creole language. Chamoiseau was one of the founders of the literary movement Créolité in the 1980s, some years after Midonet released his first 2 albums.

Crucially Gratien was always open to collaborations, eager to experiment outside of genres, to go with the flow and ignore the purists, breaking boundaries along the way. In his words:

“I always broke free from the rules, from codes being too narrow, without this being however a consciously deliberate choice. I have always had this sense of peaceful knowledge that there is no separation between genres, beings and universal things.”

Ven En Lévè (1979)

On his first LP (Ven En Lévè, 1979) he was already, rather naïvely at first, mixing up genres, singing in Créole and fusing bélè and gwoka rhythms, while adding - in a very tout monde fashion - a decidedly more European feel, opening up his music to a whole new dimension in the process. You can hear this fusion of styles on the mystical ‘Mari Rhont Ouve La Pot’, a song for which he credits his collaborator, pianist and arranger Eric Randon for the visionary ideas that perfectly matched Midonet’s sketches of the track. Gratien was all ears and all too happy to bounce off Randon’s suggestions, which led to this unique symbiosis between an acoustic folk sensibility, organic rhythms, cosmic synths, and spiritual, soulful lyrics which you can hear throughout the album. Interestingly he was unaware of other artists and bands (Roland Brival, Marius Cultier, Edmony Krater, etc) also working on a similar path of fusing traditional Caribbean rhythms with western styles like jazz, funk and soul.

As already mentioned, Ven En Lévè enjoyed great success in France and in the Caribbean, thanks mostly to its title track, and won the Maracas d’Or prize at the time. Following on from the success of his debut album, Midonet pursued a similar though less naive path for the rest of his career, now intentionally aiming to mix up genres and sensibilities.

L’inité (1980)

His sophomore album, L’inité, also on Touloulou, came out the following year (1980), when he was asked to represent ‘le mot créole’ at the “Festival du Mot Boby Lapointe”. It confirmed the uniqueness of Midonet’s world.

Between the tropical acid folk of ‘M’en ka Monté Mon’ and ‘Roulo’, the mystical and majestic sounds of ‘Kannaval Sakré Pou Tout Z’Heb Poussé’ (featuring Maurice Lagier on violin), and the cosmic reggae jazz of ‘Apré Lanmess Cé Yèp’ (not included on this compilation), the album flowed effortlessly, cementing the artist’s status as a true original.

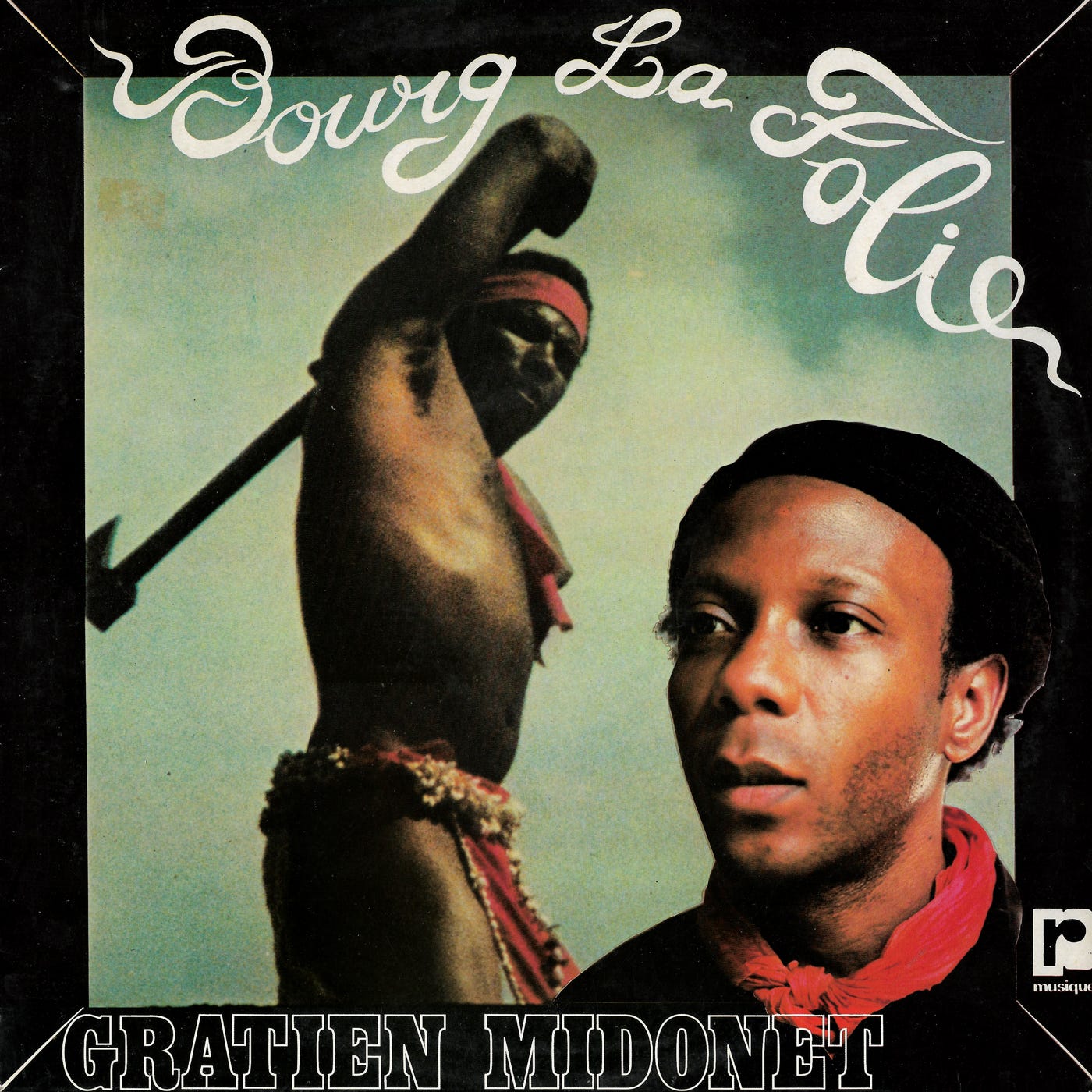

Coming out in 1984 on the short lived Paco Rabanne Design label, his 3rd record, Bourg La Folie was the soundtrack to the impressionist film made by fellow Antillean Benjamin Jules Rosette, a movie director who was also the founder of the cult ‘Théâtre Noir’ in Paris, later to become the first black cultural center in continental Europe.

Bourg La Folie (1984)

Sadly this film, which Midonet describes as “magnifique” and was centred around carnival and its spiritual impact, was only viewed by very few people during its initial theatrical run, and was never subsequently released on VHS let alone DVD. To this day there exists no known copy of the film, and one’s imagination can run freely by listening to the soundtrack while looking at the cover art of the vinyl.

While this can easily claim the title of ‘best soundtrack to a lost and hence imaginary movie ever’ (sic), there is no mystery that the music on here is extraordinary, and up there with Midonet’s best work.

Arranged by Congolese guitarist and singer Samba N’Go of M Bamina fame, and notably featuring Luther Perreau on keyboards, Amédé O Suriam on percussions and Jacky Arconte on guitar, the production on this is insanely good and shows us a tighter and more groove based side of Midonet (‘La Point' Dé Nég’), while staying loose and experimental in some of its arrangements (‘Osana’).

Fô Ou Tchimbé (1989)

A few years later (1989) came Fô Ou Tchimbé, Midonet’s fourth LP and the last one we decided to focus on for this compilation.

It came about as a ‘conte musical’ (which could be translated as ‘musical tale’ in English. It refers to a narration of - usually short - imaginary stories accompanied by music) which Midonet presented at the Centre Georges Pompidou under the title Maché Kochi, pièce pour Dits, Mimes & Masques as part of the ‘Revue parlée’, a series which focused on the oral dimension of literature.

This orality comes to the foreground on this album, even more than on any others, as you can hear and feel Midonet’s prowess with words and melodies. The Creole language smiles with joy and ease even for non French and non Creole speakers. This is the definition of poetry in music, as well as a prime example of Creole soul. His faithful collaborator and keyboard player Luther Perreau truly shines on this album, adding crisp cosmic touches to most tracks, especially on ‘Antille Ô Cristal’ which could easily be played out on the most adventurous of dance-floors in 2020.

Elsewhere Jocelyne Béroard (fellow Martinican, of Kassav fame) sings the chorus of ‘Kérozin' Jamb' Fin’, while a kora makes a surprise appearance on the majestic ‘Maché Kochi’. Once again this is totally unique album, coming deep from within Midonet’s (Creole) soul.

Still Creating, Still Channeling

Gratien released two further albums after that, and is currently based in Noumea, New Caledonia, where he spends his time between writing new songs, publishing short stories and sculpting coconuts. His cosmic message of musical unity is ready to resonate once more.

Written by Cedric Lassonde (Beauty & The Beat) in April 2020

Become a paid subscriber to unlock this month’s Bandcamp discount code 👇

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Time Capsule to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.