Interview with 'A Century in Sound' Director Nick Dwyer (Part 2)

Inside the world of Ongaku Kissa: Euan & Ayana speak with Nick Dwyer about deep listening and audiophile culture – taken from the Time Capsule takeover on Worldwide FM in October 2024 (Part 2)

In recent years, a global resurgence of interest in Ongaku Kissa—Japan’s iconic deep-listening cafés—has taken hold, with venues worldwide embracing high-fidelity sound and immersive listening experiences. In this conversation, Euan and Ayana speak with Nick Dwyer about what’s driving this movement, from vinyl’s resurgence to the parallels between listening bars and dance floors. They explore how these spaces shaped Japanese jazz, influenced artists and filmmakers, and continue to foster deep musical connections. Taken from the Time Capsule Takeover on Worldwide FM in October 2024 - Read the Part 1 from here.

Euan: Today, we're seeing a global interest in this culture—Ongaku Kissa, especially jazz kissa—in cities across the US, Europe, and here in the UK, particularly in London. Listening bars are becoming more common. Why do you think there is this growing global interest in this culture?

Do you think it has something to do with the times we're living in? Could it be connected to the revival of vinyl and a desire for more immersive listening experiences? What do you think is driving this global interest?

Nick: Yeah, I mean, there’s a lot of reasons. About ten years ago, when we first started working on the documentary series, there was virtually no foreign media on it whatsoever. But even then, I felt it was only a matter of time before people would take notice.

By the mid-2010s, articles started to appear. At first, it was seen as a curiosity, but over time, it became part of a broader movement—an audiophile movement, a listening movement, a "slow listening" movement. People like Colleen Murphy, DJ Cosmo, were already doing things like Classic Album Sundays back in 2010, encouraging deep, intentional listening.

I think people started to reconsider their relationship with music. There were events designed to make people stop and actually listen again because, collectively, we had stopped listening. Streaming and playlist culture turned music into something functional—you either danced to it in clubs, or you were at home and you would listen to playlists like music to study to, music to cook to, music to exercise to etc. You’d have music on in the background whilst you performed another task.

In contrast, in the '60s and '70s, people would buy an album, sit in front of their hi-fi system, devour the liner notes, and immerse themselves in the experience. The realisation that we had lost this way of engaging with music started to take hold.

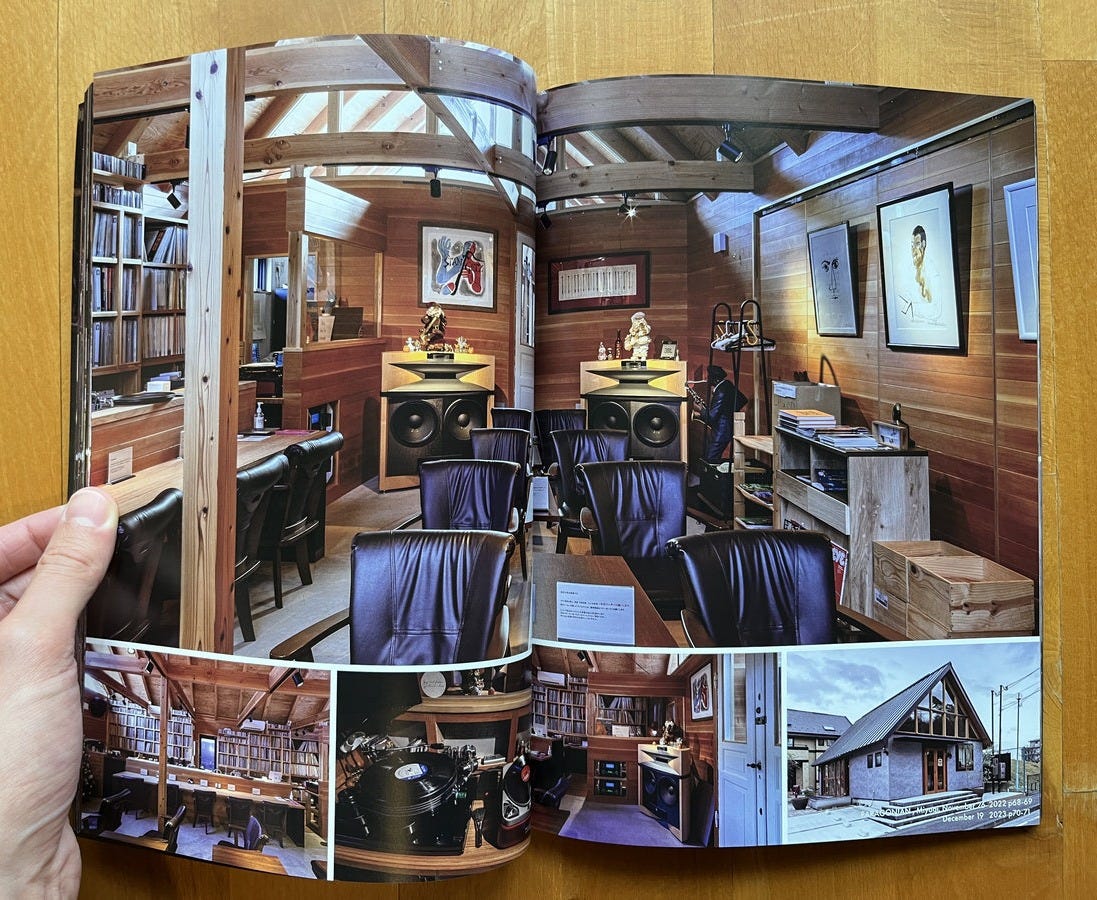

During the pandemic, we saw even more articles about listening bar culture. The more people saw images of jazz kissa and those massive speakers, the more they wanted to experience it for themselves. At its core, I think this resurgence is driven by a collective recognition that music is deeply important in our lives, yet we weren’t truly listening to it anymore.

Euan: What are your thoughts on the relationship between Ongaku Kissa, or deep listening spaces, and dance floors? These are two settings where people gather to experience high-fidelity audio.

We’re used to going to loft-inspired parties where people bring Klipschorns, and audio quality is an integral part of the dance experience. There’s a lot written about how dance floors can foster a sense of egalitarianism or even utopianism. Beyond the obvious difference in movement, what are your thoughts on any similarities between these types of places?

Nick: There are a lot of similarities, and the most obvious one is that most people go through life never hearing music the way it was meant to be heard. Over the decades, hi-fi standards have declined. In the '60s and '70s, people had home hi-fi systems built to last. Now, most people listen through laptop speakers or earbuds.

What ties these spaces together is that they offer music fans the chance to hear music properly, as it was intended. And when you do that, a whole new emotional range opens up—one that just isn’t present when you listen through other systems.

And, you know, going back to what you were saying before about the sense of utopianism and all these transcendental experiences that you can have on the dance floor over these audiophile sound systems—when you listen to music on a proper system, there's a whole frequency range, a whole emotional range that you're getting that just isn’t present on any other kind of system setup.

You hear music for the first time, and you just feel this emotion that wasn’t present before. So, for a start, I think you have these experiences—you can have these emotional experiences, you can get goosebumps—because there's this whole frequency range in the music that you weren’t hearing before.

Euan: In your research, have you come across specific musicians, filmmakers, or artists who spent significant time in their local Ongaku Kissa and drew inspiration from them in their work?

Nick: Yeah. I mean, where do you want to begin on this one?

In the 1950s, Japan was still recovering from the war. People were poor, and records were incredibly expensive—the price of a single LP could be a third of a month’s salary. No one could afford to buy records or hi-fi systems, so if you wanted to hear new music, you went to a jazz kissa.

Legendary Japanese jazz musicians like Akiyoshi Toshiko and Sadao Watanabe would go to these bars to study. They would listen intently, transcribe the music from memory, and then learn to play it for their performances that night.

These spaces were vital for the development of Japanese jazz. They were the only way young musicians could access and study new sounds. Jazz kissa like Chigusa in Yokohama were hubs where entire scenes were born.

Euan: What about artists outside of music? Have filmmakers, writers, or photographers been influenced by these spaces?

Nick: Definitely. If you look at every major avant-garde Japanese artist from the 1960s—filmmakers like Teshigahara or Nagisa Oshima, all the leaders of the Japanese Nouvelle Vague—they all hung out at jazz kissas in the sixties.

As jazz was starting to become more free, and artists like Ornette Coleman, Eric Dolphy, Albert Ayler, John Coltrane were pushing further into that freedom—that was at the very cutting edge of artistic expression.

All the filmmakers, artists, and writers were swept up in that as well. I'm sure anyone familiar with Haruki Murakami knows that before he was a novelist, he ran his own jazz kissa called Peter Cat in the seventies. In the sixties, he was a student, going to jazz kissas and getting caught up in this artistic movement.

So yeah, absolutely—anyone close to underground culture came up through this culture of Ongaku Kissa.

Euan: Dance Your Way Home by Emma Warren begins with a great quote from Theo Parrish: "Escapism has always been an adjective used to describe the dance. That’s an outsider’s view. Solidarity is what it really offers."

Do you think this idea applies to Ongaku Kissa as well? There’s a stereotype that they’re places to retreat from the world, have a whiskey after work, listen to some jazz. But in reality, they seem more about connection—understanding the owner, the regulars, and forming a community. Could you replace "dance" with "Ongaku Kissa" in that quote do you think?

Nick: Absolutely. That’s exactly what it's about.

That’s what we’re trying to showcase through the documentary series and book we’re making—that these spaces reflect the personalities and passions of their owners.

People who come and engage with this culture—no one's going there to get wasted. No one's going there to escape. They're going there to, yes, step into a world, but it’s the world of the record, the world of the artist. They want to get as close to the musicians as possible. They want to get as close to Coltrane and feel like they’re in there.

But they’re not trying to escape anything. They’re stepping into a musical world, but there’s no escapism happening in these places. And that’s what I love about it. It’s about community—it’s about you, the owner, and the regulars sharing these incredible musical experiences together.

This month's discount code for paid subscribers 👇

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Time Capsule to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.