Kay Suzuki: The Space Between the Beats Defines Our Time

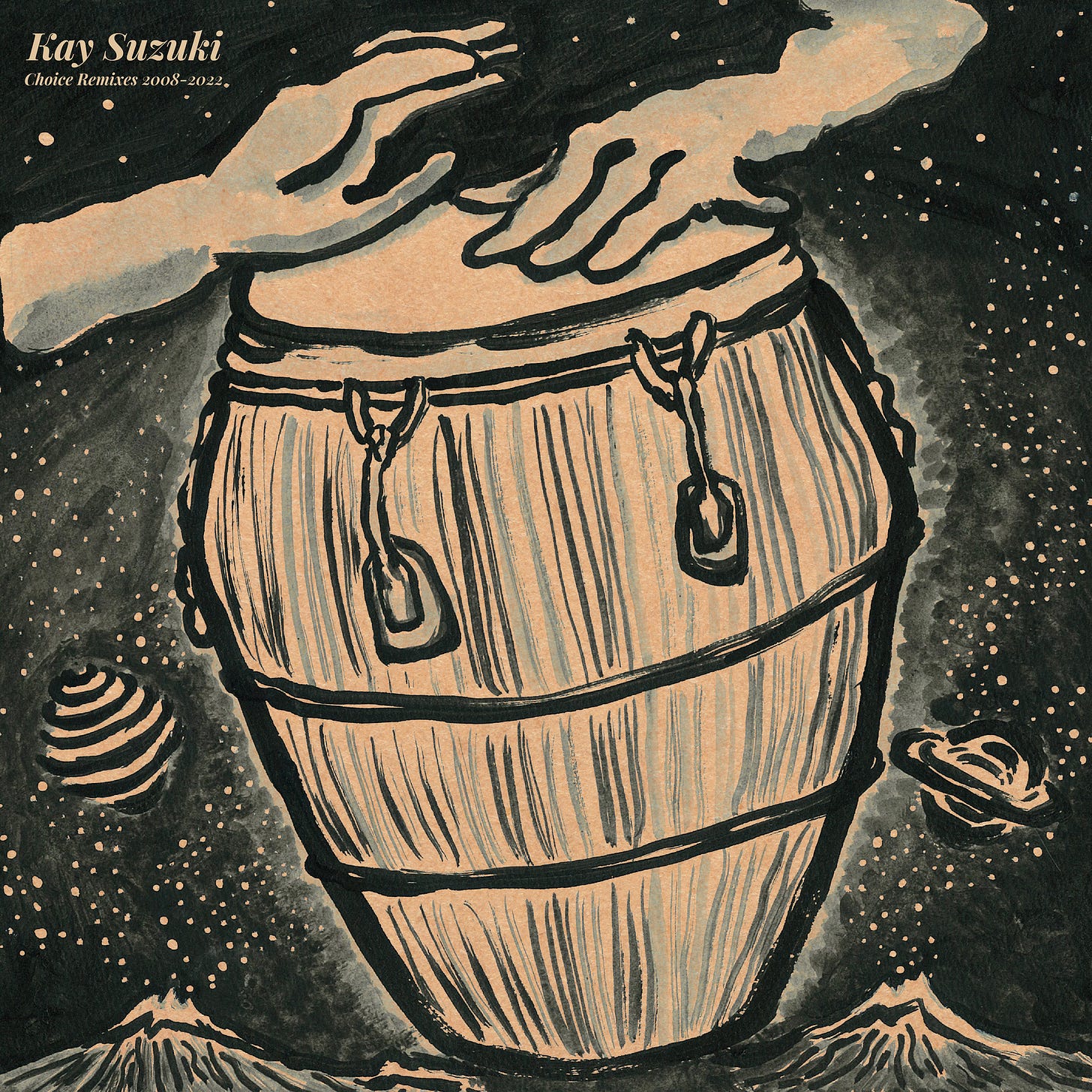

Flipping rhythms from Guadeloupe, Cuba, Senegal and Puerto Rico, Time Capsule founder Kay Suzuki shares an acid-soaked collection of remixes that transcends time and space.

It’s only a few minutes into my conversation with Kay Suzuki about his new collection of remixes and already we’re in heady territory. I’ve known Kay for several years and regularly written liner notes for his releases on Time Capsule, but this is the first time that I’ve had the chance to ask him about his own philosophy of music, and particularly, what he’s drawn to when he hears a track for the first time. “Unique rhythms,” he responds. “The kind of music that has a very distinctive groove, a very distinctive space between the beats.”

It’s a simple idea but one with resonant implications. How a rhythm feels is determined less by the beats than the time between them. Rhythm is time, but it is also space. Presence and absence. Positive and negative. “Listen to I.G. Culture, Osunlade, J Dilla, Fela Kuti, James Brown,” Kay elaborates. “You only need to hear one second, just one beat between the kick drum and the snare drum, and you can already feel that it has that sense of timing.” He doesn’t explain what that means, but the implication is enough.

The artists Kay lists are as good an indication of the contours of his musical world as any - broken beat, house, hip-hop, afrobeat and funk spiral around one another in a vortex of interconnected rhythmic influences. As a child growing up in a sleepy Japanese suburb, Kay’s musical education was strictly American rock and soul, administered by his father and brother, schooling him in the swung time of Stevie Wonder and Ray Charles - artists he’d play to his friends in the hope that they too might feel that feeling. Going to school opposite the biggest Disk Union record shop in the country, Kay would skip classes to work in a sushi restaurant, paying his wages straight into a record collection that was just as likely to contain Kraftwerk and Led Zeppelin as it was Parliament-Funkadelic.

I push him a little to elaborate on what appealed to him so intensely about this music. “These artists created their own way of counting the time, feeling the time, outside of conventional clock time or metronome time,” Kay explains. “When they create that time feel, I feel like they are creating another universe, and we're drawn to that universe. Our body is drawn from the normal clock-time frame-of-mind into their frame-of-time, so we have to adjust our body to dance to it.” I think of the times I have lost myself on the dance floor, when an evening becomes a lifetime, and both frame-of-mind and frame-of-time are lost to the world outside.

To equate rhythm with time is to crack open the possibility of what music can do, but articulating a feeling as ineffable as that which makes you move can be fiendishly difficult. In a piece for the London Review of Books about J Dilla, Francis Gooding describes the hip-hop producer’s sense of time in porous terms as “effervescing at the border between conscious perception and bodily feel,” something at the edge of known world, that blurs our relationship with the linear and, like Kay suggests, opens out towards another realm of experience. “A sense,” Gooding continues, “of being held in uneasy suspension, like that moment at the top of a swing when the upward momentum fails, the weight comes off the chains, and you seem to float for a fraction of a second before gravity pulls you back down.”

Just as it is the space between the beat that makes the rhythm so does Kay identify that it is not just percussion, but an interplay of instruments that is responsible for creating the unique sense of time which he is chasing. He points to this collection’s first track, ‘A Ka Titine’ by Gaoule Mizik as an example. ‘A Ka Titine’ is a Gwoka track from Guadeloupe, based on the toumblak rhythm, a party rhythm denoting love and happiness that Kay laces with electronic influences, dub sirens and space echoes, leaning into the music’s creole roots in the process. This is toumblak time on another plain, a new musical universe forged in the collision of rhythmic influences.

In recent years, Kay has been reading about Buddhism and quantum physics, both of which swerve our conception of linear time towards ideas of relativity and simultaneity. He is fascinated by the way in which the Mayan calendar escapes the lockstep of its Gregorian counterpart, dialling in only to pay its taxes, and has found his obsession with time supplemented by a decade or more experimenting with psychedelics. His first album, released in 2010, was called Consciousness and one of his releases on Time Capsule was introduced to him by a shaman on an ayahuasca trip.

Remixes too, Kay suggests, are versions of time-space expansion that take a received rhythm and imagine it on new terms. He describes them as conversations, not just between the original artist and its remixer, but between two distinct notions of time. “It's my interpretation of how they feel time,” he explains, picking the example of Blackbush Orchestra’s ‘Sortez, Les Filles!’, which opens the B-side of this record. Originally released by Beauty and the Beat, ‘Sortez, Les Filles!’ is one of the more heavily reworked tracks on the collection, taking apart the original and kneading the West African percussion into a chugging Balearic house track, buoyant and full of life. “I felt the potential from the original percussion,” Kay explains. Putting it in a new context, he flipped the beat, looped and manipulated it “to create my own feel of time.”

Kay Suzuki moved to London in the early 2000s to do a vocal course, drawn to the hybridity of a club scene that was open to exploring convergences between genres and styles that he had not experienced in Japan. He became obsessed with broken beat, attending CDR and Co-Op at Plastic People, which he credits for helping him understand what music could do when played on a good sound system in the complete darkness to a room full of dancers effervescing, to re-tool Gooding’s phrase, at the border between conscious perception and bodily feel.

The second track on this collection is drawn from Kay’s time orbiting the world of Co-Op, which gave him a footing in a London scene he was still relatively new to. Originally released as part of a CD compilation put together by Afronaut of Bugz in the Attic, Broki’s ‘Es Que Lo Es’ emerged from another cross-cultural collaboration, this time between Bugz (Afronaut and Seiji) and local musicians in Puerto Rico. Kay’s remix slips the Afro-Latin percussion into a subtle bruk, weaving a third space between London and San Juan that, fifteen years on, remains both of and outside the era in which it was made.

Alongside Plastic People Kay found his new spiritual home at Beauty and the Beat, an itinerant party built on the solid foundations of hi-fi sound and funky apricots. Alongside the would-be founders of Brilliant Corners, Kay hauled the speaker stacks back into the van at the end of the night, a right-of-passage for acolytes of psychedelic audiophilia. “Beauty and the Beat was revolutionary for my consciousness,” he says. “The concept of having great sound made me realise I love all kinds of music again. Even in tracks you know, you hear something that you have never heard before.” Good sound is all about balance and, of course, the space between the elements.

In 2013, Kay was invited to come up with a menu for a new audiophile bar and Japanese restaurant that was opening in Dalston, London, called Brilliant Corners. What he did was apply a theory of sound to a theory of flavour that would be similarly balanced and rounded.

“You need to have that experience that makes you satisfied,” he explains. “The bass frequency is the soup stock, it's the umami, you don’t really feel it on the top of your tongue but if you don’t have that soup stock, miso soup wouldn’t taste like miso soup. If you don’t have the bass frequency, then you don’t really feel your groove. The mid frequency is the meat of the song, that's the melody line, that's the thing that you match with the main ingredients. The sauce is the harmony that's put on top of the melody. And the high frequency is wasabi, lemon or spring onion, that cuts through everything to give that crispness.” Attention to detail. Using the right ingredients. It all seems to speak back to the art of the remix.

Kay gets there ahead of me. “And when you mix music, as you do as a mixing engineer, you want every instrument to be heard, you want to have the right balance of low, mid and high frequency. You want to be able to taste all the ingredients, so you want to be able to hear all the instruments clearly.” It’s not surprising then that after leaving Brilliant Corners, Kay went on to take the job of mixing and mastering engineer with Doctor Mix, owned by friend and multi-instrumentalist Sunlightsquare a.k.a. Claudio Passavanti.

It was at Doctor Mix that Kay honed not only the art of mixing records, but of releasing them too, collaborating on the label and co-producing the original version of Sunlightsquare’s ‘Oyelo’, featuring Cuban vocalist Rene Alvarez, which closes out this collection. As if to illustrate his point that rhythm is about the space between the beats, Kay snuffed out the kick drum to leave only an implication - the absent presence of a groove - or what he calls an “imaginary four-to-the-floor”. Rhythm as space, rhythm as feeling, rhythm not played but rhythm felt, in the body of the listener, time rearranged, extended, morphed, scrambled, stretched and reassembled in a haze of vocal blips, piano stabs and snare claps. The hope that the space between the beats might last forever, held, at the top of the swing, before plunging down and up again into the next, leaving you, for a moment at least, floating in another universe entirely.

It is significant perhaps that the rhythms which underpin these four tracks hail from Guadeloupe, Puerto Rico, Senegal and Cuba. Rhythms of the Black Atlantic, where the space between the beats hold as many stories as the beats themselves. I end by asking Kay an impossible question. “How do I feel time?” he repeats back to me, before pausing to try and find words that might do justice to that which comes so intuitively in sound. "I'm just obsessed with the concept of time. Even without music. Philosophically, spiritually, scientifically, I'm constantly analysing how I feel time,” he muses. “These remixes are just the result of my thought process.”

Anton Spice