Mario Rui Silva: Stories From Another Time

The roots of Angolan popular music explored in the meticulous guitar studies of polymath Mário Rui Silva.

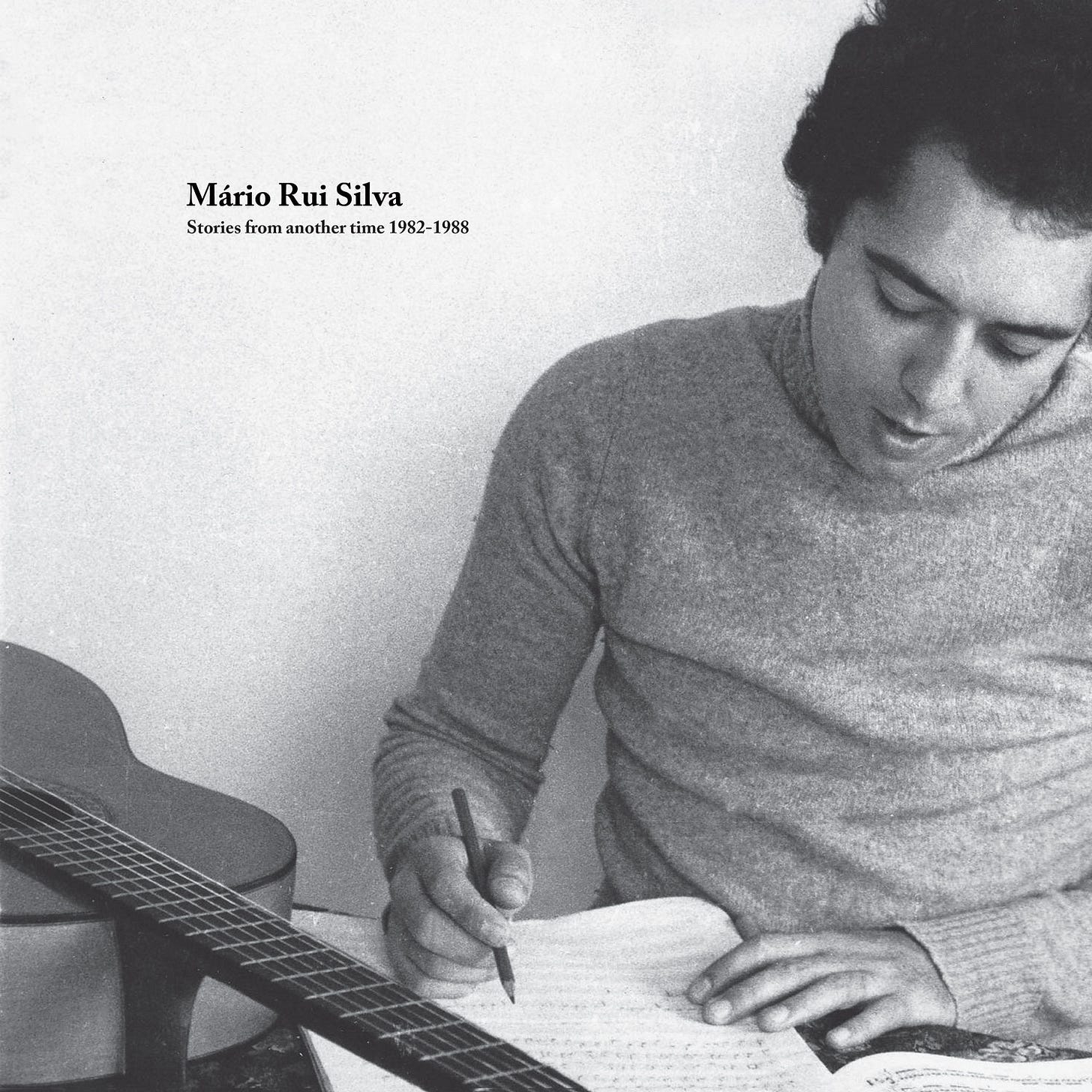

The first chord Mário Rui Silva learned to play was an A minor. He was nine years old, receiving impromptu guitar tuition from his younger sister, Paula, in what was a musical household. Silva’s father played the guitar and his mother sang, learning the popular repertoire from Italy, France and Brazil. They were, in Silva’s words, part of the petit bourgeois population of Angolan capital Luanda under Portuguese late colonial rule. Born on 8th March 1952, he was twenty-three by the time Angola gained independence in 1975.

Mário’s musical journey began in earnest a decade earlier as part of Os Jovens, a band of school-age musicians conducted by his father, for whom Silva was lead guitar. Popular throughout the 1960s, Os Jovens provided Silva with the foundations to take his solo electric guitar playing to new heights, and by 1966 he had left the group to pursue training in the instrument with a vigour and dedication that would go on to define much of his work.

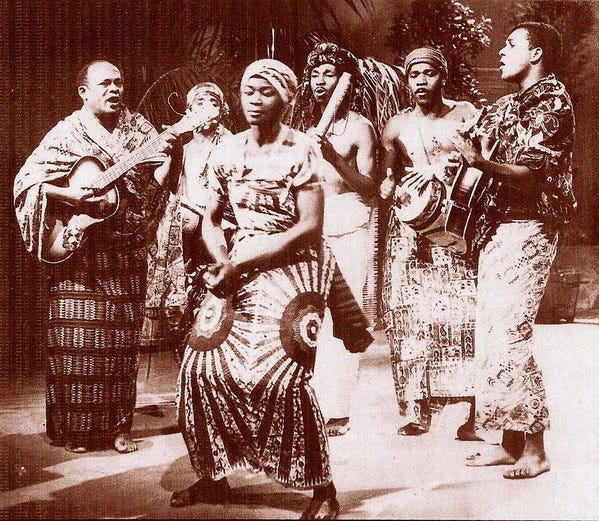

The style that captured Mário’s imagination was semba, a traditional form of Angolan rhythm and dance revitalised by the group Ngola Ritmos in the 1940s and ‘50s. Tuned in to Luanda’s “Tondoya mu kina o kizomba” radio programme, the impressionable young guitarist heard renditions of songs like ‘Nzaji’, ‘Mon’ami’, ‘Muxima’ and ‘Mbiri-mbiri’ that would provide a new perspective on the European standards he had played with Os Jovens. “What attracted me to this music was that it was different to what I knew,” Mário explains. “I dreamed of seeing these songs projected internationally and wanted to learn them.”

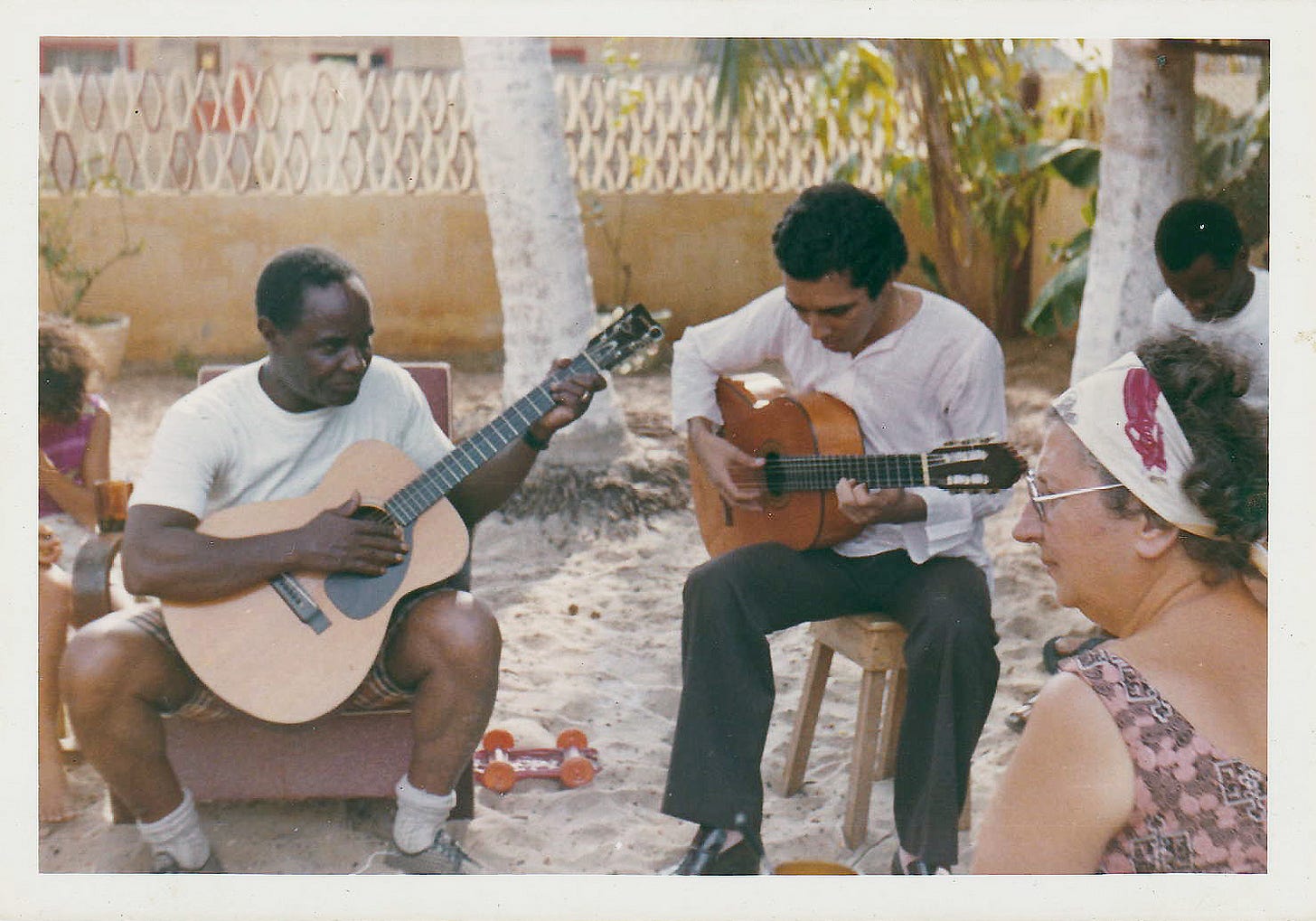

In 1969, Mário was exposed to semba and its adjacent style, kazukuta, directly for the first time when he was asked to accompany Duo Ouro Negro, one of the first Angolan groups to tour internationally and build a reputation outside Africa. It was here that he also became closer with Carlitos, the son of Liceu Vieira Dias and another formative figure in Mário’s ongoing musical education.

Liceu was one of the founding members of Ngola Ritmos, a group of five musicians formed in 1947 who were the leading exponents of modern Angolan semba and kazukuta - a sound defined by the dikanza, or scraper, and the ngoma drum. A forerunner of styles such as samba, kizomba and kuduru among others, what set the semba of Ngola Ritmos apart was not its tradition, but the cosmopolitan flair with which they incorporated European instruments like the acoustic guitar. It was a combination which reflected the movement of the Angolan population from rural to urban areas at the turn of century, and the new reality of life in the suburbs of the capital city.

Like their contemporaries, the semba rhythms of Ngola Ritmos emerged from the miseke, or informal settlements, of Luanda, in casual musical exchanges and neighbourhood dances. Through its ability to connect with a wider audience, aided in no small part by the advent of radio, semba coincided with, and helped propel, a renewed sense of Angolanidade, or Angolan identity, that would underpin the country’s push for independence.

Singing in Kimbundu, a Bantu language spoken in Luanda, Ngola Ritmos gave fresh significance to traditional funeral laments and work songs, nudging the population towards a positive and potentially emancipatory sense of national pride and collective agency. As Marissa J. Moorman writes in Intonations: A Social History of Music & Nation in Luanda, Angola, from 1945 - Recent Times, “music created an experience of cultural sovereignty that served as a template for independence.”

As an activist for the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), Liceu was on the front line in the struggle for independence, but it was his subtle ability to communicate a universal sentiment through his music that most fascinated Mário. “Liceu changed the major tones of traditional, popular music to minor tones, chords that were used in fado, because the population was more sensitive to this sequence of chords,” he explains. “He [Liceu] thought it was the only way to indirectly draw the attention of the population to be more interested in local things from the land, so that we could become independent.”

Such was the power of the music to awaken its listeners to the oppression, racism and tyranny of colonial rule that Liceu and bandmate Amadeu Amorim were imprisoned by the Portuguese, first in Luanda and then the infamous Tarrafal prison in Cape Verde. Liceu spent ten years in incarceration, and was only released shortly before he and Silva first crossed paths, outside a Duo Ouro Negro show at Luanda’s Ngola Cine venue in 1969. It was a meeting which would shape Mário’s life from then on.

“[Liceu] was a thinker, a philosopher,” Mário described, in an interview with Dias Dos Santos. “The answers he gave to the questions he was asked were full of “maybe... [or] it seems like..." He didn’t wave absolute truths. He was a new old man, always willing to learn. He was an artist without actually being one.”

Not content to just learn the songs of Liceu and Ngola Ritmos, Mário set out to research their stories and origins. It was a coming of age moment for the young musician, who described the feeling to Carlos Alberto Alves in 1996 as a “total surrender, body and soul, to the music of a land that saw me born.”

Still only a teenager, this would first take place outside of Angola. With his father’s blessing, Mário travelled to Lisbon to continue his studies amid the embers Salazar’s Portugal, before heading to Belgium to visit his older sister, herself in political exile. There, Mário fell in with Cape Verdean musicians and members of the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC), among whom was guitarist Humbertona.

Having met fellow Angolan musician Bonga in Lisbon, Mário introduced him to Humbertona with a view to recording an album. A few days later, they were in Rotterdam to cut Angola ’72, an album of high significance for Angolan music, born of exile and defiance in Northern Europe. Indirectly at least, it is an album Mário believes would not have been possible without his father’s support.

Mário returned to Luanda in 1972, in time to see Angola claim its hard-fought independence three years later. However, with the country slipping into civil war and the promises of independence evaporating into political turmoil, it was not long before he reentered what he calls his own “voluntary exile”, heading this time for Paris and eager to continue his studies.

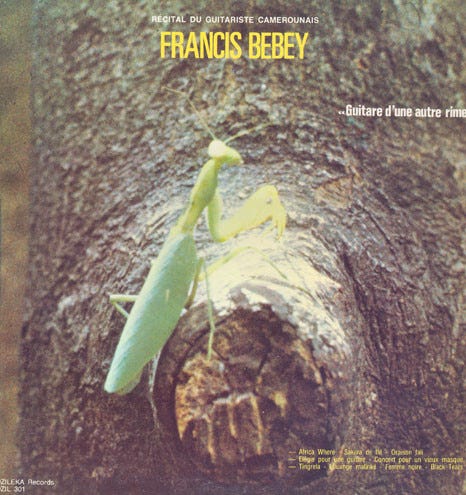

“Paris was a laboratory,” Mário describes. “The fact that I met African musicians led me to draw comparisons [between the music of different countries].” He remembers meeting Manu Dibango, who lived nearby, and being invited to Francis Bebey’s house with his family, where Mário had the opportunity to quiz the Cameroonian musician and writer about the intricacies of his 1975 classical guitar album, Guitare de Une Autre Rime. The track ‘Despois de Uma Conversa’, from Mário’s 1986 album Tunapenda Afrika, features a melody written after a phone call with Bebey.

“When I arrived in Paris around 1979/80, I came to learn,” Mário explains. “I had the chance to meet people from Senegal, Mali, Guinea-Konakry. I heard a lot of music from the Sahel region. I think this contributed to my self-training.” The first album to emerge from this time was Sung’ali, recorded and released in Luanda in 1982. It was a marked shift from his previous release As Pessoas, o Meio e o Tempo four years earlier, and combined what he calls a “Salada Russa” or “Russian salad” of mixed influences into his sound. There is however a clear thread to semba in much of Sung’ali - the dikanza and ngoma keeping time, the finger-picking articulation of the acoustic guitar and a sense of rhythmic intricacy that folds itself around the central melody of each track. Included on this compilation, ‘Dembita’ was inspired by Guinean musician Aboubacar Demba Camara, whose music Mário first heard while working in a restaurant. The poignance of ‘Ngele-Ngele-Ngele’, which evokes the sense of the suffering felt by those not able to live with dignity in their homeland, is clear. Carlitos features on the recording, as does his father, if in name alone, on ‘Lamento pra Ngola Ritmos”.

To lay ears, the music has a wistful and melancholy quality. A sense of longing is woven into the dynamics of Mário’s deft guitar playing, while the morality tales and reverential vernacular root his personal touches within the broader tradition of Angolan popular music. What might sound like the more familiar intonations of Brazilian and Caribbean influence are what Mário attributes to the “African rhythms taken by the slaves [which] gave rise to other musical cultures'' around the globe. Any sonic similarities to the acoustic guitar music of Brazil, be it bossa or samba, are, in Mário’s eyes, “sonorities that were left in the memory of the people at that time.” This was the collective instinct to assert a contemporary cosmopolitan identity free from the patronising falsehoods of Lusotropicalism.

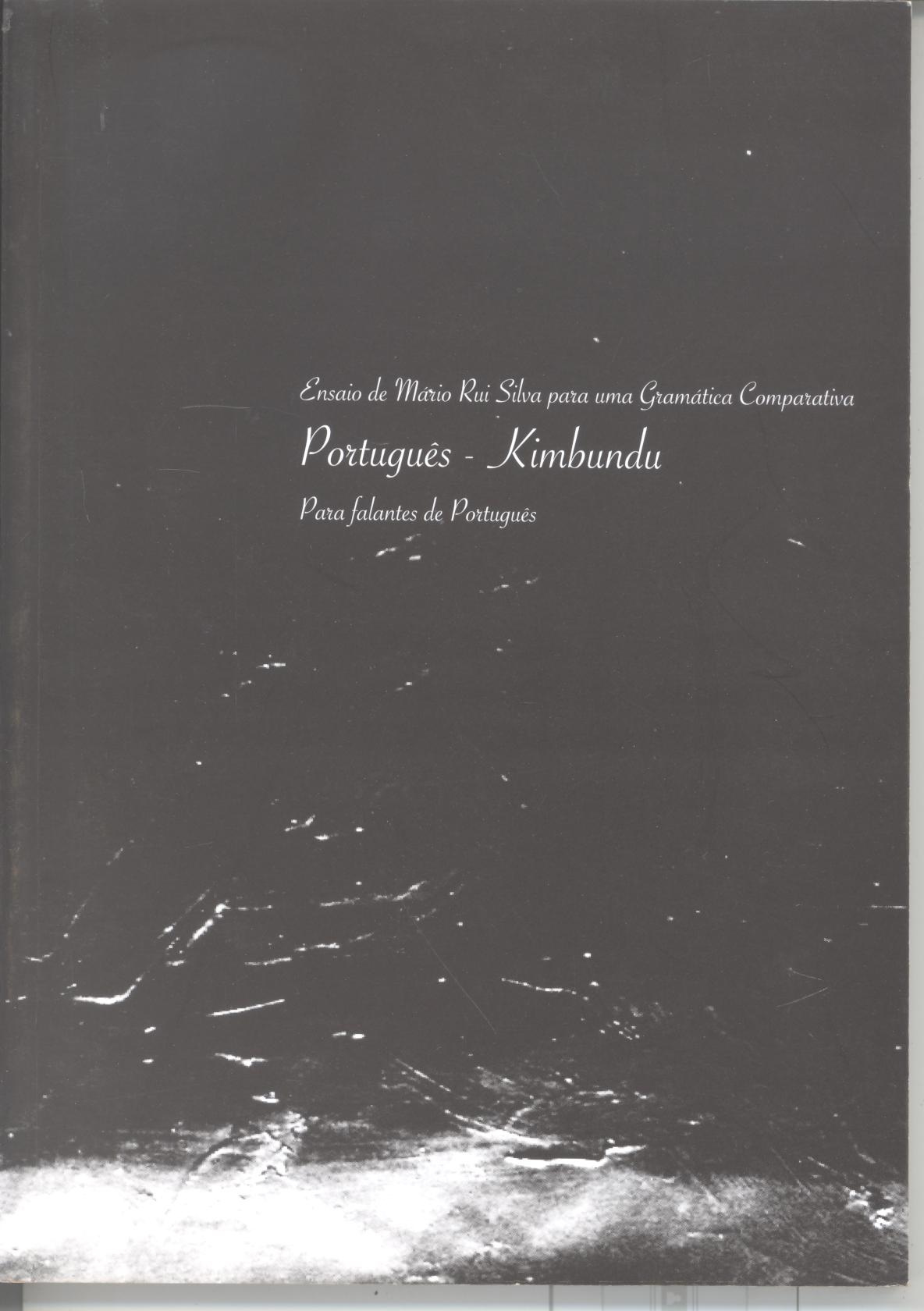

Lyrically, Mário also retained Liceu’s dedication to Kimbundu, which evolved in parallel to his musical explorations. A firm believer in the power of study to engender self-determination, he dedicated himself to the practical task of writing a new “Comparative Grammar of Portuguese-Kimbundu” - a feat of lexical endurance which he hopes might facilitate its wider learning. That Angola’s national languages were not taught in schools, as had been promised following independence, was a major regret.

Released three years after Sung’ali, Tunapenda Afrika showcased a further broadening of the horizons Mário had experienced in Paris, as hinted in the album’s Kiswahili title. While the dikanza and ngoma are still present, the introduction of Nandinho’s saxophone and Kinitu on electric bass gave the album a more jazz-inflected feel. On the silken ‘Lembrança dum Velho’, it even errs towards a groove-led fusion sound - the electric keyboard of Marito recalling something of Azymuth’s José Roberto Bertrami in its fluidity.

“I didn't have a focus at the time,” Mário explains. “I was making the records according to what I was composing, based on new information and new input.” By the time he released Koizas Dum Outru Tempu in 1988, these influences can be heard in the hypnotic refrain of ‘Kazum-zum-zum’, the kora on ‘Kora Kya Ngola”, and the kisanji on ‘Kizomba Kya Kisanji’. The latter imagined the traditional Kizomba dance as played on a kisanji - a lamellaphone of the Cokwe-speaking people of eastern Angola, most familiar to fans of Francis Bebey as a sanza.

“There was a need within me to contribute in doing new things and to want to contribute with the steps that the music was taking,” he describes. “In the sense of solidifying the music of Angola that was the result of the meeting of two cultures, and wanting to value the Angolan part whenever possible.”

As such, Mário’s music looks in several directions at once - back to Ngola Ritmos and the origins of semba and kazukuta, through the lens of Portuguese influence, and towards an Angolan future. For Mário, semba, like Kimbundu, is not fixed in the past, but alive, mutable and has something to say to a complex modern world accelerating beyond its roots. Mário would go on to develop his own guitar - the ‘Ngita-Mbinda’ - which used a calabash as a sounding board in order to increase the clarity, fidelity and articulation of the rhythms he was studying. He has since combined his research on the history of Angolan popular music into the book, Stories for the History of Music in Angola, and formalised his guitar method in theory textbook, The Teaching of Music, which posits a periodisation of Angolan music, from the late 15th century to the early 21st.

Like Liceu, Mário does not speak in absolutes, but in nuances, tones and textures. “Without contradictions, there is no realization,” he once told Mario R. Rocha. “There must always be a negative to find a positive.” While he is unequivocal about the value of Angola’s musical and cultural heritage, he makes no claims to being anything other than in service of the cause. On the back cover of both Koizas Dum Outru Tempu and Tunapenda Afrika is a dedication of thanks to those involved in making these records “a worthy homage that we surrender to Africa through our music.”

Describing himself as culturally mestiço, there is a searching quality to much of his work. It is encapsulated by the idea of raizes, which translates directly as “roots", but which Silva articulates as “looking for something that our ancestors could have given us and did not give us because of colonial times.” It is heard in the first chord he learned as a nine-year-old child, in the minor progressions of Liceu’s semba, and throughout the music on this compilation.

“Roots. It is a very interesting topic,” Mário told Mario R. Rocha. “I think it has to be placed within a certain context, because in the generation I live in, among the composers in which we find ourselves, when we talk about roots, we talk about identification, that is, going looking for something.” It is that which seeks to bridge the brutal rupture of colonialism, the imprisonment of the country’s cultural leaders and the collective urge to reconnect with ancestral origins. To engage in the search is even more important, when you know you may not find what you are looking for.

Anton Spice

⬆️ Mario Rui Silva and band live at Giant Steps in London, 2021

Please please please re-press this beauty