Niningashi: A Japanese Acid Folk Gem Lost to Time

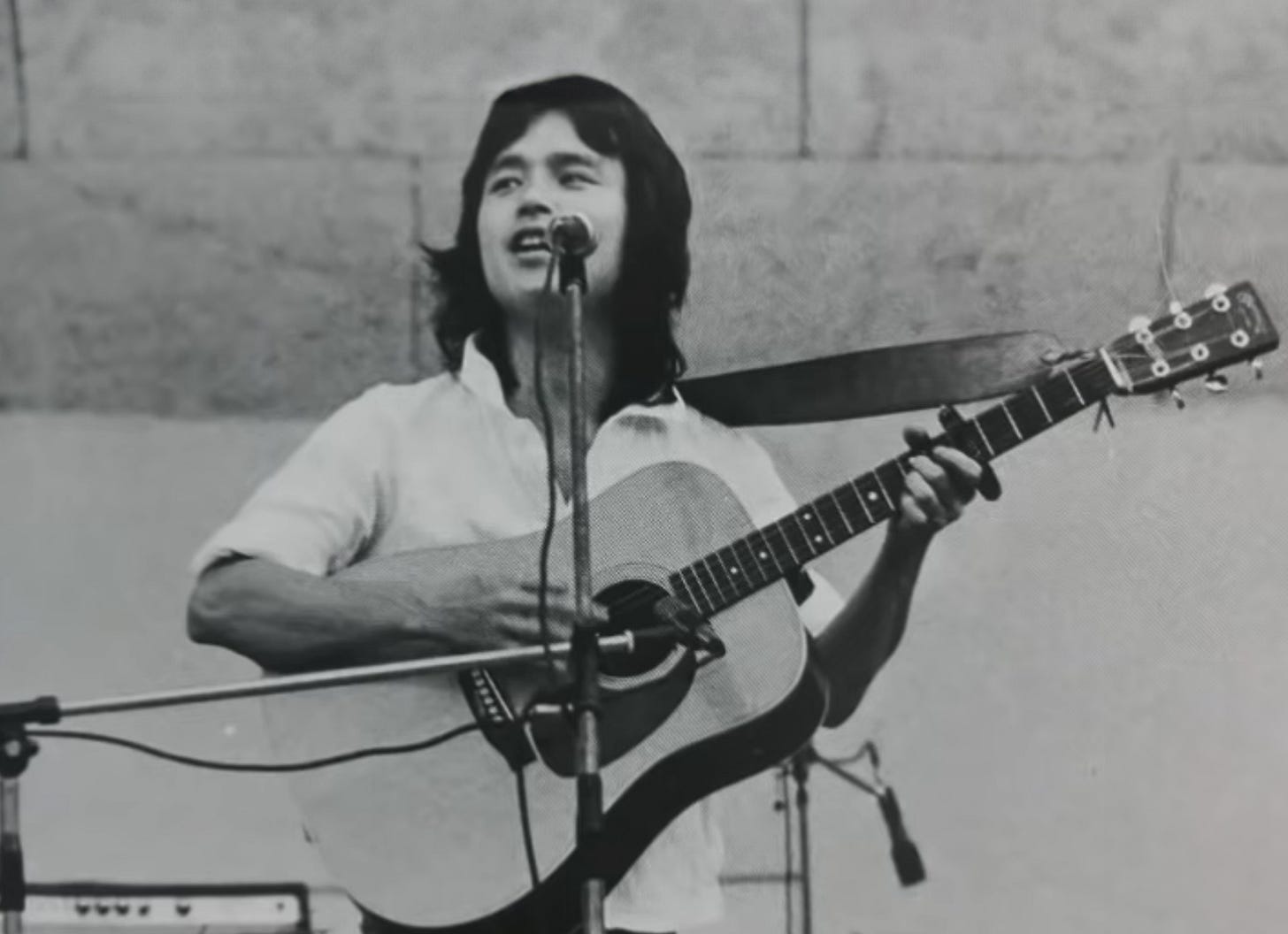

Although he was training as a pharmacist, Kazuhisa Okubo was much more interested in prescribing musical medicine.

Musicians spend their lives writing songs that no one will hear. Sketched melodies, scribbled chords, notebooks full of lyrics, metaphors and observations that will never find one another in the shape of a song.

Occasionally, these pieces do stick together, gravitate towards one another, form a structure and begin to build a life of their own. A melody just right for a turn of phrase, cute enough to carry a chorus to a verse and back again. Less frequently, the shapes these songs become are carried from the fleeting will of the musician into something a little more permanent, transformed from a thought into a thing.

Recorded, mastered and pressed into solid form, these songs become objects – records in every sense of the word - to hold and play and share and pass into the flood of other records that snag for just long enough so that others may hear them too. Before long though, these too will float away, leaving little trace.

But that’s not always the end of the story. In the pursuit of lost causes, every now and then a record like this one will be plucked from the river and returned to the shore, where you might find yourself reading about it.

Niningashi’s Heavy Way has spent almost 50 years so far downstream even its creator, Kazuhisa Okubo, had let it go. For most of that time, the erstwhile composer and guitarist worked as a pharmacist in Tokyo, no longer concerned with the songs he did or didn’t write.

To be an aspiring musician in the early 1970s was to be caught up in the changing tides of Japanese folk and rock. US and European influences had saturated the market, but amid the copycat acts and commercial ventures, innovative musicians like Haruomi Hosono were seeking new currents. His first major project, Happy End, staked a claim for Japanese lyrics in the rock space that sent ripples across the country, inspiring many of the artists featured on Time Capsule’s twin compilations of Nippon Psychedelic Soul and Nippon Acid Folk, which also includes Niningashi .

Born in Hiroshima in 1950, Okubo studied pharmacy in Tokyo, as much to assuage his parents as follow his passion for paracetamol. A full-time student, Okubo’s song writing would likely have taken a backseat, but it's hard to imagine he wasn’t right there in the mix, enjoying the Tokyo scene and soaking up as many influences as possible. One song on this record feels more autobiographical than the rest:

Once again today,

Alone in an empty room,

I smoke cigarettes.

I feel no motivation.

In my small room.

Strumming my guitar in a corner,

Sipping coffee,

I sing lousy songs.

In my small room.

A folksy, washboard ditty complete with harmonica solo, ‘Semai Boku No Heyade’ (In My Small Room) it seems to project if not a reality then a yearning in the mind of the young pharmacist, housebound with his dreams - a little depressed and a little self-indulgent, willing the life he wanted from the confines of the life he already had.

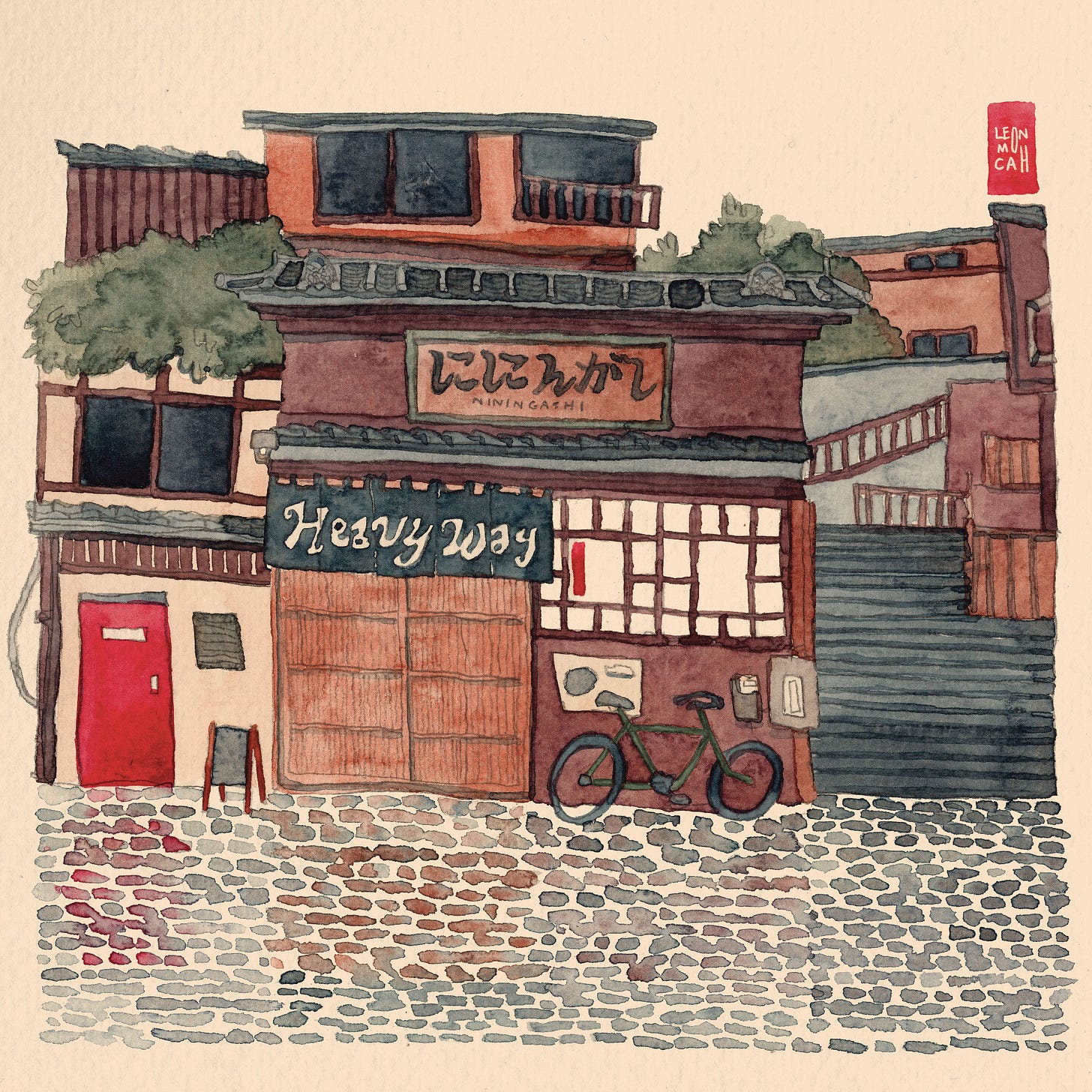

While many of those “lousy songs” likely never made it beyond the walls of that small room, Okubo was ultimately given the opportunity to make an album as a reward from his parents for completing his degree. Niningashi, which translates as ‘two times two equals four’, was the name of his band and Heavy Way, released in 1974, was the name of the record. It was a moment in Okubo’s life where surely nothing else would have felt more important.

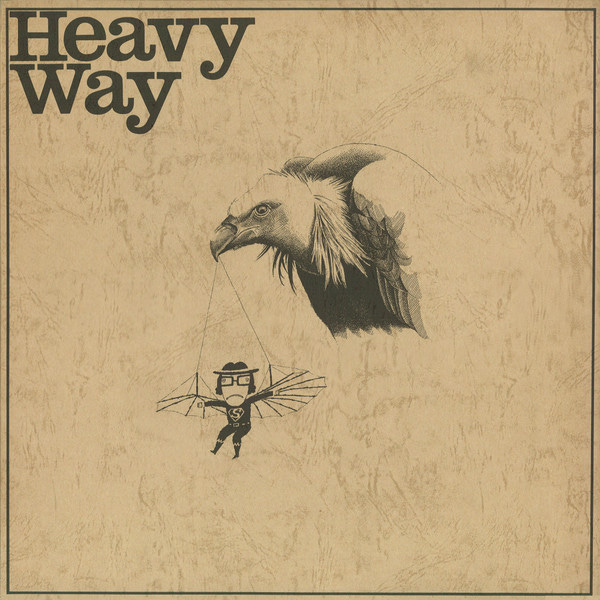

A family affair, Okubo asked his brother, an aspiring illustrator who had also moved from Hiroshima to Tokyo, to create the artwork. Perhaps the bespectacled character on the cover is Okubo, a reluctant superman, suspended from make-shift wings in the mouth of an eagle, unsure whether he’s flying on his own or being carried by a higher power. In the studio, his brother’s girlfriend mocked him for singing so quietly, a naivety in his voice more suited to small rooms than large studios.

Alongside friends gathered from his school days, Okubo and Niningashi recorded nine songs. Many are pastoral in their themes, recalling textures, sounds and atmospheres of a rural life Okubo may or may not have experienced. Sandals, mandarins, temple bells, chestnut forests, village elders, tea houses and cotton kimonos. They speak of nostalgia for an old Japan, a lost Japan, an innocent Japan, where the wind is gentle, the sun warm and it is always just about to rain.

Set against these wistful images are the accoutrements of cosmopolitan life. Coffee and cigarettes are ever present, as is a kind of modernist urban ennui drawn from Europe and transposed on the anonymous, sprawling futures of 1970s Tokyo. This world is more hostile, less innocent, and one track in particular stands out. ‘Chikan no Uta’ is a graphic tale of sexual abuse and perverse male desire on a packed Tokyo subway train. With heavily distorted guitars and confrontational vocals, it hints at a sordid undercurrent in modern Japan society, one which Okubo was perhaps struggling to assimilate with his own values and desires. Satirical maybe, but ambiguous nonetheless.

Sonically and thematically it is a world away from the other tracks on the album. Had he been signed to a label, someone might have had a word. As it was, Okubo and Niningashi pressed the album privately and self-released it in such small numbers, those remaining have fetched close to £1,500. One by one, copies of Heavy Way drifted down the river and out of sight.

For Okubo, the end of Ninigashi was not the end of his music career. For two years between 1973 and 1975, he played with folk outfit Neko before joining up with fellow songwriter Shōzō Ise as Kaze. Together they released five studio albums on Nippon Crown between 1975 and 1978, three of which reached no. 1 in the Japanese Oricon chart. These were songs that people did hear, and Kaze’s popularity was significant enough for fans to greet a change in style from pop-folk to jazz-rock with ambivalence. Three solo albums followed for Okubo, but they would not reach the same heights. In 1981, he retreated from music for good, returning to the quiet life of a pharmacist in a big city, with a box full of records that might or might not have ever been heard again.

Although Okubo did ultimately taste a degree of success, the image of the young man, disillusioned and distracted, strumming out harmonies and smoking cigarettes in his small student room feels closest to the sentiment of Niningashi’s Heavy Way. Aged twenty four, Okubo couldn't have known what was to come. One imagines his hopes dashed by the reception (or lack thereof) to Heavy Way, and applauds his resilience to keep going for another seven years, until he finally ran out of road.

Okubo died in 2021, but had he known you’d be reading about Heavy Way today, he might have smiled. To be satisfied with a small room is better than being dissatisfied with a large one. As the final verse of ‘Semai Boku No Heyade’ (In My Small Room) suggests, Kazuhisa Okubo knew this too.

Sometimes, I wish for a spacious room

To relax, but somehow,

I've grown fond of this room,

My small room.

Anton Spice