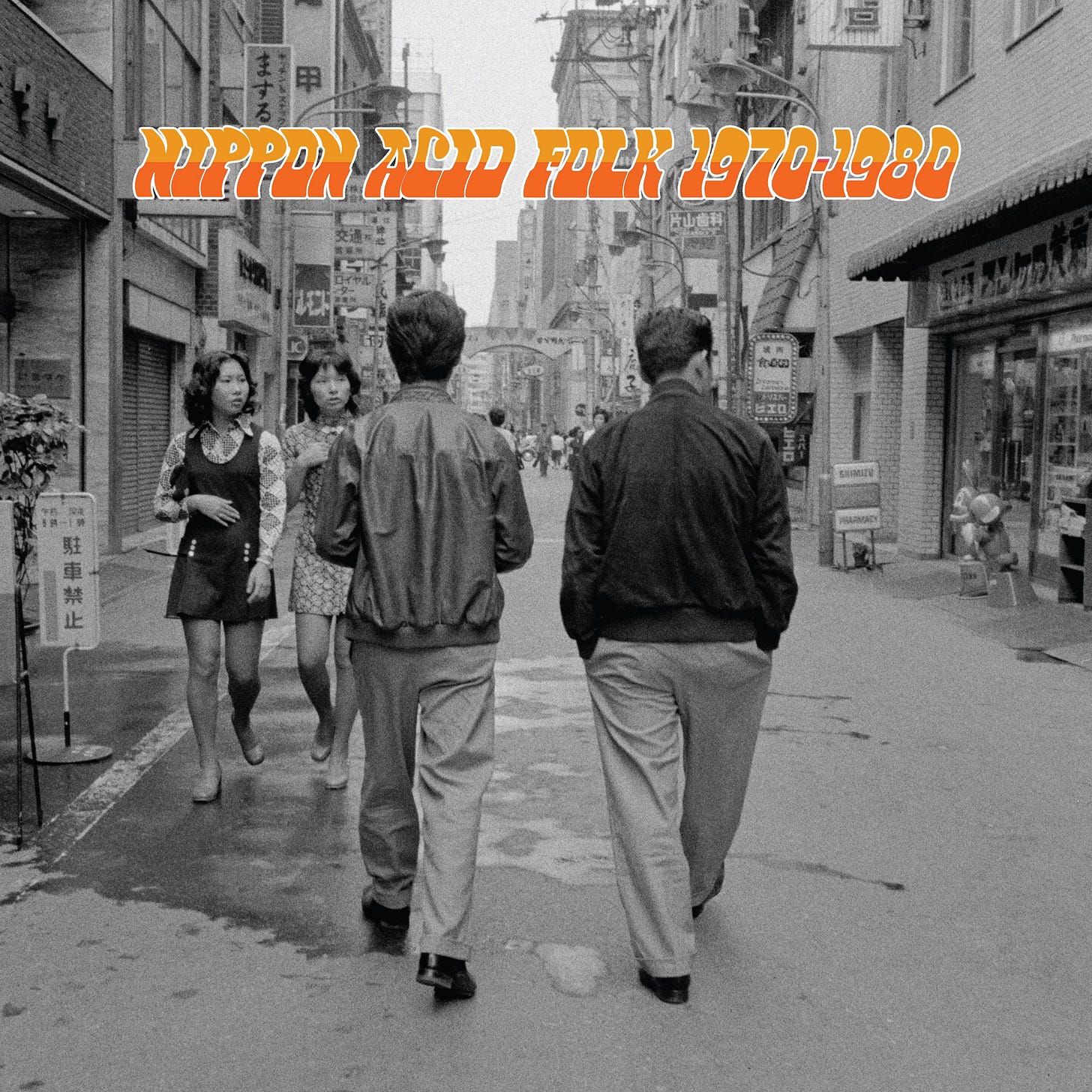

Nippon Acid Folk: The Story of a Nascent Counterculture in Japan

Japan's 1970s counterculture was united by expansive, experimental, and deeply soulful sensibility. Challenging the status quo and changing the country’s music industry in the process.

The birth of Japan’s nascent acid folk scene was rooted in the messy and invigorating political climate of the late 1960s. It is a story of Dadaists, communists, pharmacists, and cult leaders, led by a young generation of upstart students, artists, and dreamers hellbent on turning their world upside down.

Born on the campuses of Tokyo, Kyoto, and Osaka, and centred around newly formed independent labels and left-wing stronghold URC, this uniquely Japanese form of folk expression provided an outlet for musicians who were tired of aping Western sounds and instead found ways to sing in Japanese and integrate traditional forms in new ways.

Obstinately uncommercial, relentlessly creative, the music featured on Nippon Acid Folk 1970-1980 represents a broad church of influences.

So here the story goes…

In January 1967, Joan Baez was invited to attend anti-war meetings held by student organisations in Osaka and Tokyo. As in the United States, a youth protest movement was gaining momentum in campuses across Japan and folk music was its soundtrack. Over three thousand people gathered across both events, rapt by the American singer’s renditions of ‘Blowin’ In the Wind’ and ‘We Shall Overcome’, and eager to channel those messages of resistance into Japan’s own nascent protest music.

Although the Vietnam War was a central concern for Japanese students, a sense of defiance was bound up with geopolitical relations closer to home. Since the end of the Second World War, sporadic protests would erupt against the continued presence of US military bases on home soil. That the US Air Force was now using its base in Okinawa to launch attacks against Vietnam only made their grievances more urgent.

Japan’s relationship with Western cultural influence was similarly complex, and contradictory. Trends and musical movements were often embraced and assimilated with remarkable speed, causing a tension with both traditionalists who baulked at the dilution of Japanese culture, and the avant garde, who felt that anodyne reproductions of Western styles were holding back the potential for more radical forms of expression. Music became the barometer of a culture finding its feet in an increasingly globalised world.

As pop music from the UK and the US began to infiltrate Japanese culture in the mid-1960s, two connected scenes emerged. On the one hand, the so-called British invasion propelled by Beatlemania left a trail of copycat bands in sharp suits with thinly veiled one-word names like The Spiders. Singing in English and marketed through mainstream channels, they were loosely known as “Group Sounds”. On the other you had “College Folk”, which focussed on the reproduction of folk pop songs from the US (such as Peter, Paul & Mary) and was played by a similar demographic of mildly rebellious middle-class twenty-somethings. Although they could be seen as stylistically and politically divergent, neither Group Sounds nor College Folk bands from Tokyo were doing little to unsettle the dominant structures that guided both the Japanese music business and society at large.

Things were a little different outside the capital. Kansai, the western region home to the three major cities of Kyoto, Kobe and Osaka, has always had a slightly edgier reputation. If Tokyo was Paris, then Osaka was Berlin – the edges of society frayed a little more keenly there, and it’s not surprising that the country’s more radical musical movements have taken root among the okonomiyaki stands of its bustling urban sprawl.

In Kansai then it was the more overtly political sounds of Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan that had the biggest influence. One young man who took their message to heart was Nobuyasu Okabayashi. A theology student and son of Christian minister from Kyoto, Okabayashi made waves in 1968 when he took the stage at a “Folk School” concert in Kyoto in 1968 to perform his expletive-laden polemic ‘Go-to-Hell Song’ (‘Kuso Kurae Bushi’) - a not-so-subtle attack on the church of his upbringing and the hypocrisies of the establishment. Japanese record labels still existed within the commercial orbits of technology companies who made the hardware that the music was to be played on. Slated for release on Victor Records in 1968, the track was moth-balled by the music industry’s ethics committee.

Even so, ‘Go-To-Hell Song’ proved to be a turning point, and it was just little over a year until it was ultimately released. For that to happen, a new chapter in Japanese music history needed to be written.

“We believe that the Japanese record industry is currently only playing a one-way role in bringing music culture to the masses. Despite the fact that there are many excellent songs that were born from the people and created by the people themselves, due to various restrictions, the songs and singers that can be commercialised are only a small part. Therefore, we gather things that are excellent but cannot be put on a commercial basis, record them with our own hands, and produce and distribute records only for club members.”

A manifesto of sorts, it was with these words that former communist party member Masaaki Hata launched Underground Record Club (URC) in February 1969, Japan’s first independent record label. What began as a subscription service to circumvent the increasingly belligerent ethics committee quickly blossomed into a fully-fledged record label. By the end of the year, URC had scrapped its membership scheme and signed distribution deals with 130 record shops around the country

First out of the door was an album by Wataru Takada, whose satirical ‘Let’s Join The Defence Force’ took aim at the militarisation of Japanese society and was initially mistaken by the actual government Defence Force as a pro-recruitment drive. The son of a Communist activist, what made Takada’s music particularly important however was not so much the strident nature of its socio-political messaging but the form with which he was composing.

As well as drawing influence from his US counterparts, Takada was also looking back to Japanese music history for inspiration. Although its modern incarnation has tended towards saccharine balladry, earlier forms of the traditional enka style were more strident in their themes, often providing a space for social or political commentary. With much of his debut album adapting enka roots, Takada was beginning to solve the conundrum that plagued Japanese protest songs: how to be both true to itself and the Western influences that lit the fire to begin with. That the song was blacklisted by Japan’s commercial broadcasters’ association, only widened the chasm that was emerging between the underground scene and officially sanctioned music industry channels.

As the 1960s ticked over and the student protests dispersed, there remained a sense that something had shifted. Japan now had the beginnings of an alternative music infrastructure and a tentative blueprint from which to find its own sound.

It is from 1970 then that the music on Nippon Acid Folk begins.

The end of the decade hit Nobuyasu Okabayashi particularly hard. Like many around him, he saw the collegiate optimism of the previous three years dissolve in a haze of repression and in-fighting, and he felt the need to step away and find a new approach.

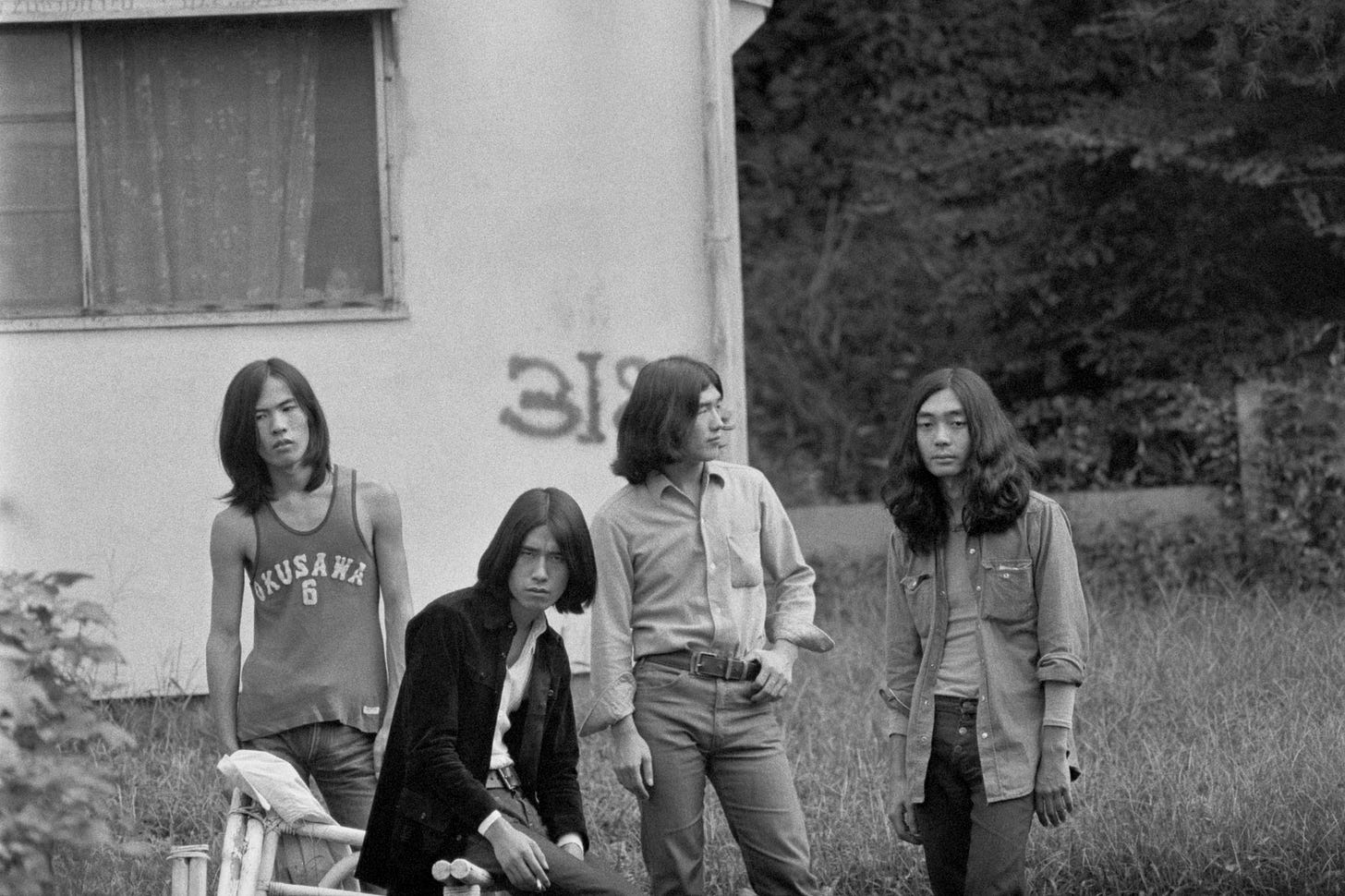

In early 1970, Okabayashi was back in Tokyo attending a rehearsal of Haroumi Hosono’s latest project Happy End. While it was as a member of Yellow Magic Orchestra that Hosono would find international acclaim, it was Happy End that cemented his legacy at home. Founded in 1969 alongside Takashi Matsumoto, Eiichi Ohtaki, and Shigeru Suzuki, Happy End entered the fray as the popularity of Group Sounds and College Folk was beginning to wane. Engaged in a public falling out with Yuya Uchida’s Flower Travellin’ Band – a popular if pastiche psych rock outfit inspired by Jimi Hendrix – about their continued use of English lyrics (in what would become known as the “Japanese-language rock controversy”), Hosono and Happy End were instead looking for ways to write music that accommodated the cadences of their native tongue.

Already signed to URC for their debut album, Happy End’s first appearance on the label was instead as the backing band for Okabayashi, who was so enamoured by what he heard at that Tokyo rehearsal that he immediately engaged Hosono and co. to electrify his previously acoustic set-up. In August, Happy End did release their self-titled debut, drawing inspiration from the likes of Buffalo Springfield, CSNY, Chicago and The Grateful Dead on what was generally considered to be one of the first rock albums sung entirely in Japanese.

The Happy End track ‘Kaze Wo Atsumete’ which is featured on Nippon Acid Folk is taken from their second album, Kazemachi Roman, released on URC in November 1971. The band’s preoccupation with modernisation played out in the album’s central conceit, penned by drummer Matsumoto, a knowingly nostalgic paean to Tokyo before the developments brought on by the 1964 Olympics. It too was sung entirely in Japanese. The times were changing, but Happy End was just the beginning.

A contemporary of Nobuyasu Okabayashi, Takashi Nishioka was considered one of the pillars of the Kansai folk scene. Born in Osaka in 1944, he went on a musical journey familiar to many Japanese teenagers in the early ‘60s, obsessed first with The Beatles and then P.P.M. and The Brothers Four. By the end of the decade though he was finding his own way, hosting listening sessions and performing across the region. In 1967, he formed the group Itsutsu no Akai fusen (Five Red Balloons), whose debut album appeared alongside Wataru Takada’s Lets Join The Defence Force on URC’s first long-player.

The following year, Nishioka formed another group, Tokedashita Garasu Bako (Melting Glass Box), for a one-time studio album from which the track ‘Anmari Fukasugite’ is taken. Featuring a cameo by Haroumi Hosono, and now heralded as a cult record in Japan’s psychedelic awakening (feted by Julian Cope’s Japrocksampler), the self-titled 1970 album was, in Nishioka’s words, more interested in traditions of Dadaism than the drug-induced flights of fancy that saturated so much of American counterculture.

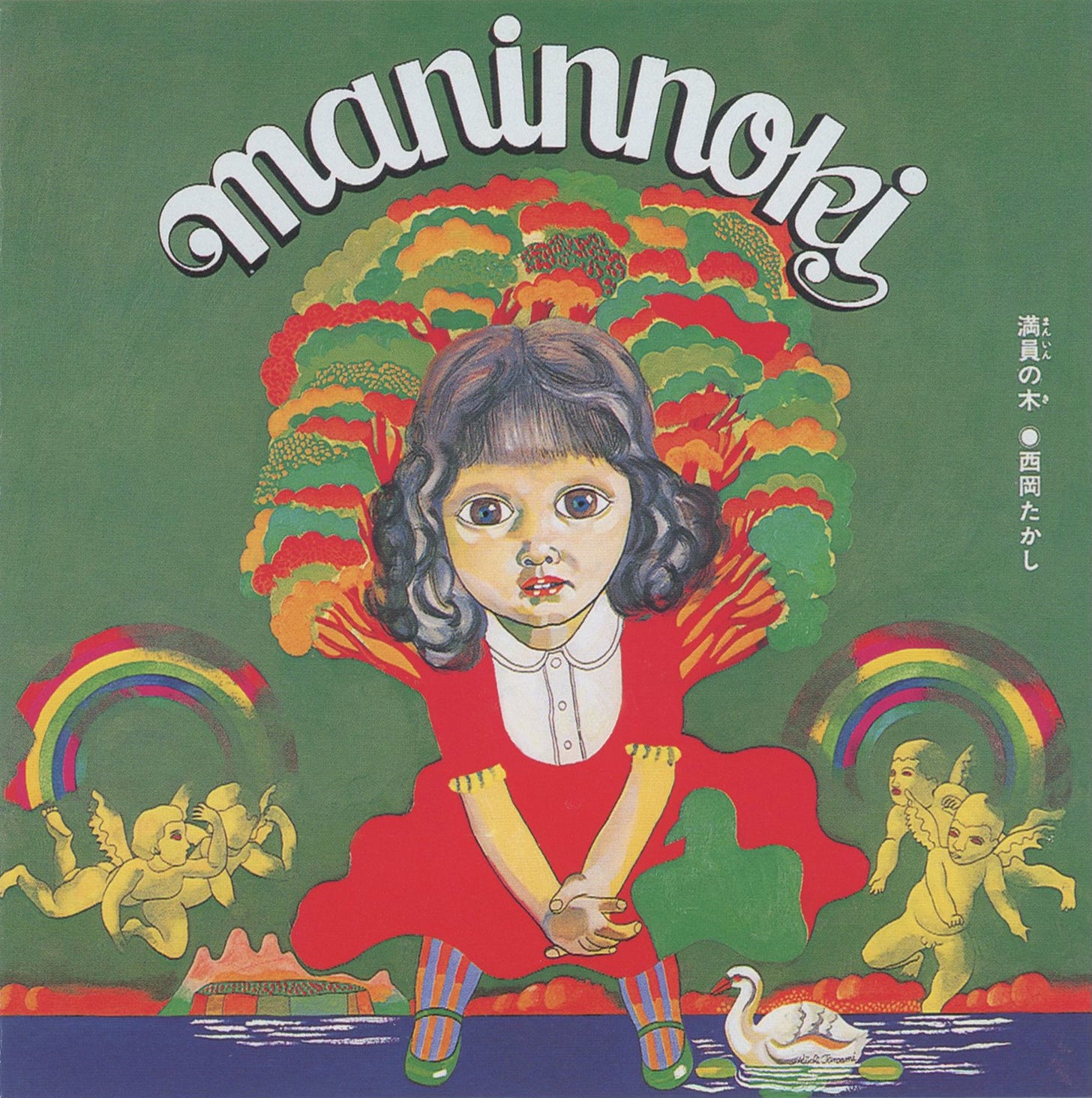

With the disbandment of Itsutsu no Akai Fusen, Nishioka turned his attention to solo recording, and in 1973 released Man In No Ki on URC, the album which lends its name to another Nishioka track featured on this collection. In a stark break from his group work, ‘Man In No Ki’ showcased the breadth of Nishioka’s multi-instrumental prowess, on which he composed, arranged, sang and played almost every instrument himself. A landmark in multitrack recording, the record also demonstrated the delicacy with which Nishioka treated his Japanese lyrics.

Akai Tori, or The Red Bird, were another group to emerge from the Kansai folk melting pot, founded by Etsujiro Goto as a five-part vocal group named after a popular series of children’s magazines. Although perhaps most famous for a 1971 single they released called ‘Takeda no Komoriuta / Tsubasa wo Kudasai’, (the latter of which became something of an unofficial anthem in Japan), the group began life on the independent scene, releasing their debut single on URC.

Courted by Kunihiko Murai, the founder of Alfa Records – home to YMO among others – Akai Tori released ten records in the four years between 1970 and 1974, the last of which featured the track ‘Hotaru’, included here. Underpinned by their trademark vocal harmonies, the track was written by Toshiyuki Watanabe and has shades of Jon Lucien in its dreamlike arrangement.

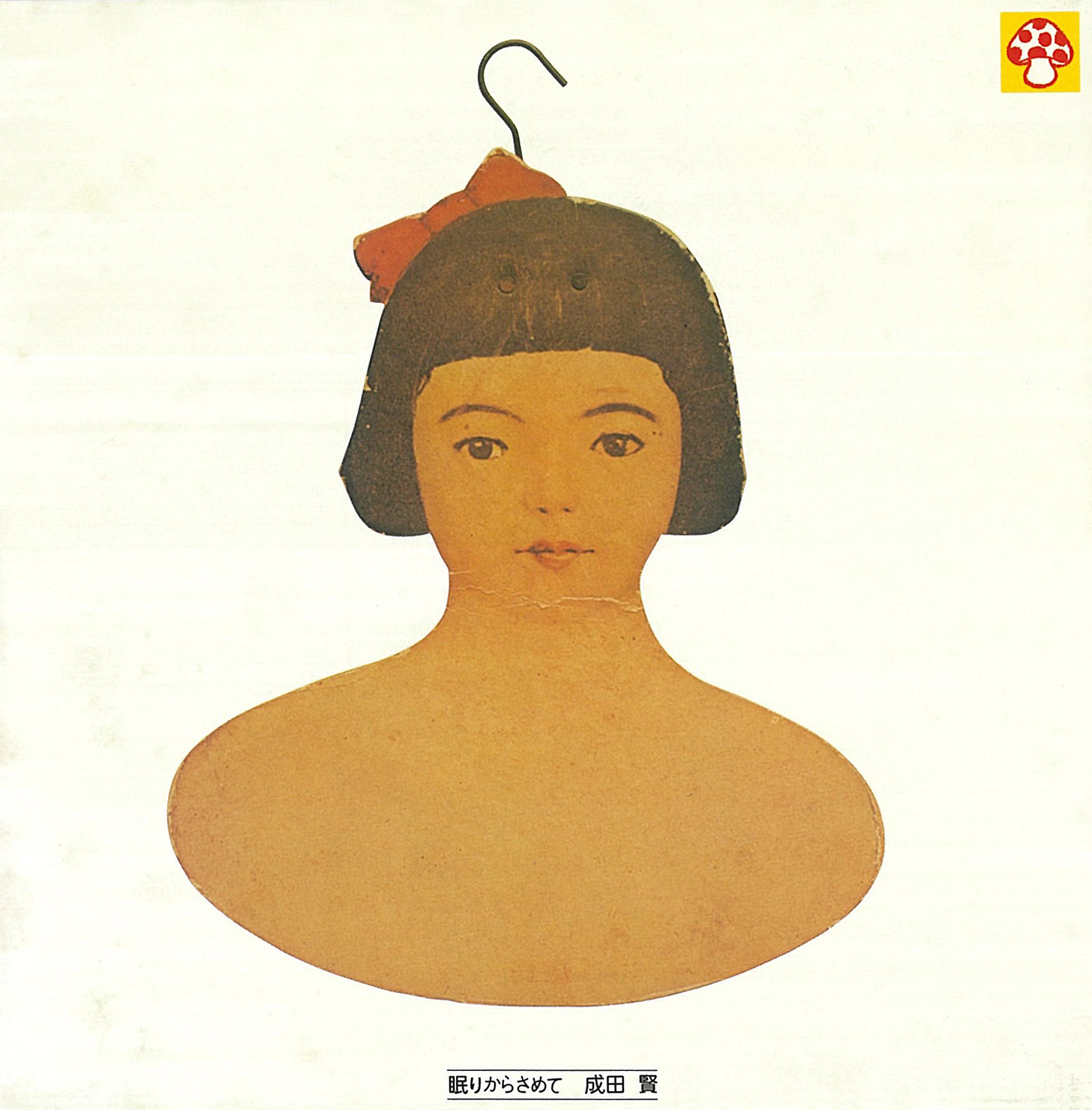

If there’s a musician on this collection who demonstrates just how interconnected this corner of the Japanese folk-rock scene was in the early 1970s, it’s Ken Narita. A member of successful Group Sounds band The Beavers, Narita went on to play Cream and Zeppelin covers with offshoot group Emotion, before going solo to release Nemuri Kara Samete in 1971, which featured Happy End’s Shigeru Suzuki. It is from this album that the track ‘Ginga Tetsudo No Yoru’ is taken. Narita would go on to perform alongside Happy End, and release a second solo record the following year, which now also stands as an early touchstone in the Japanese folk-rock canon.

While there is a temptation with underground scenes to produce their own cliques, the nature of this music’s free-spirited message also propagated in unexpected ways. URC and Happy End may have been magnetic points around which early ‘70s Japanese folk-rock gathered, but there were always going to be artists like Kazuhisa Okubo, who internalised its autonomous impulses to find their own sound.

Born in Hiroshima and trained as a pharmacist, Okubo formed Niningashi while at school, enlisting his brother’s illustration skills to provide the artwork for what would be the band’s only album. Released in 1974, self-recorded and privately pressed, it is from this record that the track ‘Hitoribotch’ is taken. By the start of the following decade, Okubo had called time on his life as a musician and found a job in a pharmacy instead.

Okubo may have been an outlier, but it is with the archetypal nonconformist that both sides of this compilation begin, and with whom it seems right to end this chapter of the story. Hiroki Tamaki’s career has been defined by a resistance against traditional form. Born in Kobe and raised in a Zen temple, the young violinist found his first professional engagement with the Tokyo Symphony Orchestra and immediately rebelled against the 12-tone temperament on which Western classical music was built. A proponent instead of just intonation, Tamaki returned to the fold in 1975 to release Time Paradox, a sweeping prog-rock odyssey that featured synth maestro and honorary “fourth member of YMO” Hideki Matsutake. It would be another four years until Tamaki found himself once again working with an orchestra, this time for the synth and strings epic Kumoino Hototogisukoku.

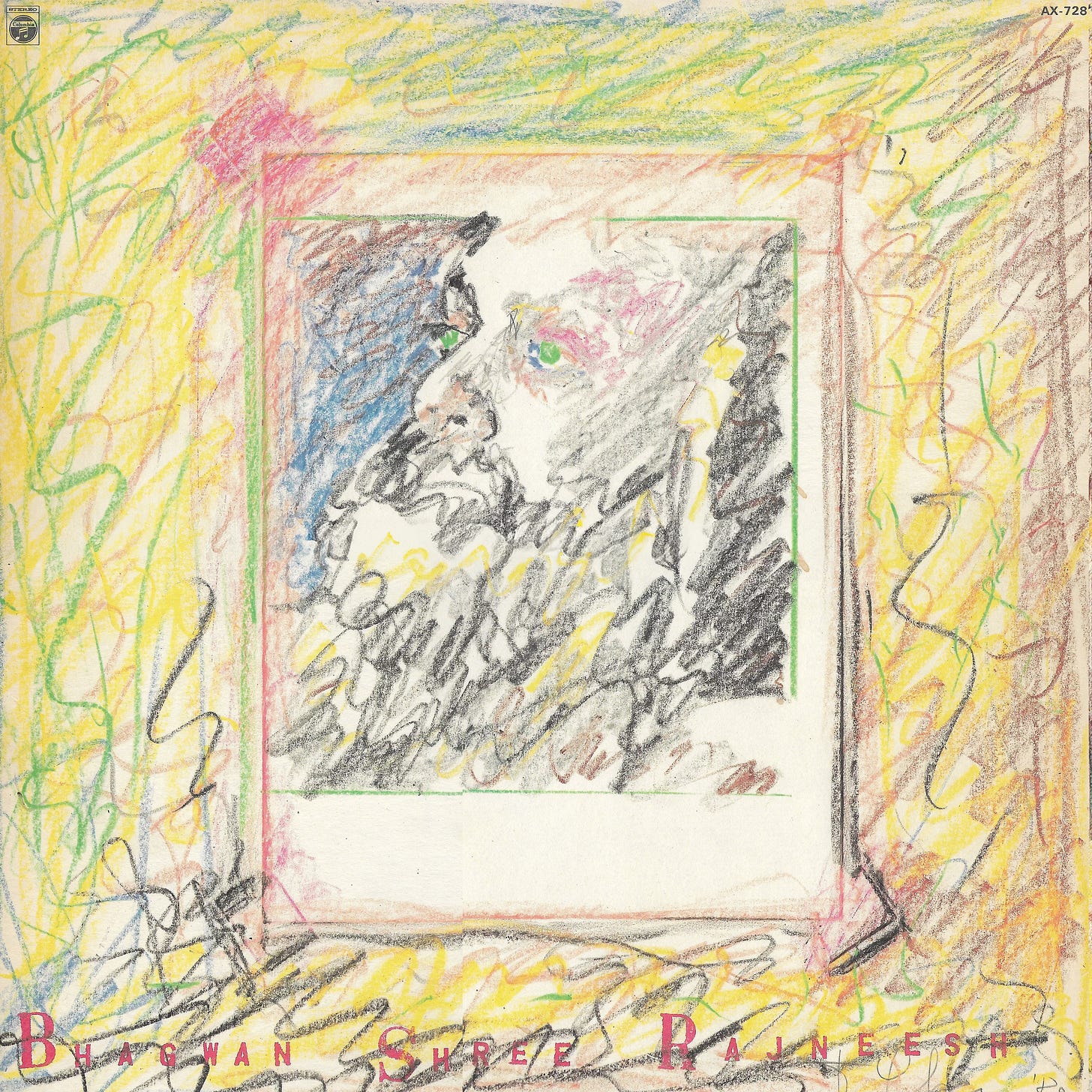

A year before its release Tamaki came across the teachings of infamous religious leader Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, also known as Osho, and by 1980, Tamaki had translated this new-found obsession into a full-on tribute album named after Rajneesh himself. “I have no confidence that I understood Rajneesh's teachings properly, but in my own understanding, life is a powerful protest against those who cannot move freely due to habits of all kinds, regardless of religion or system,” he wrote in the liner notes that accompanied a 2009 CD reissue of the album.

It’s not hard to see why Tamaki’s renegade tendencies were attracted to a doctrine of self-actualisation such as this. With artwork by Japanese graphic designer Tadanori Yokoo (whose credits include Haroumi Hosono, Santana and Tangerine Dream) Tamaki’s Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh contributes two tracks on this compilation, ‘Kawa’ and ‘Beautiful Song’.

While not always directly connected to the protest music that emerged at the tail end of the 1960s, there is something about a story that begins with Joan Baez and ends with Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh that also traces the contours of the tumultuous decade of folk and psychedelia in the United States. In 1981, Osho relocated his operation to the Rajneeshpuram commune in the Oregon hills, which quickly became embroiled in controversy, the dream of political and spiritual liberation in tatters.

And while acid folk may have had its moment in Japan too, it did not die. Instead, another more soulful, electric sound was emerging simultaneously that took its psychedelic influences and iconoclastic impulses in a different direction. To trace its origins, we need to return to 1970, Happy End, and the moment Japan’s independent rock sound began to fragment into a million colourful pieces.

Written by Anton Spice & Kay Suzuki

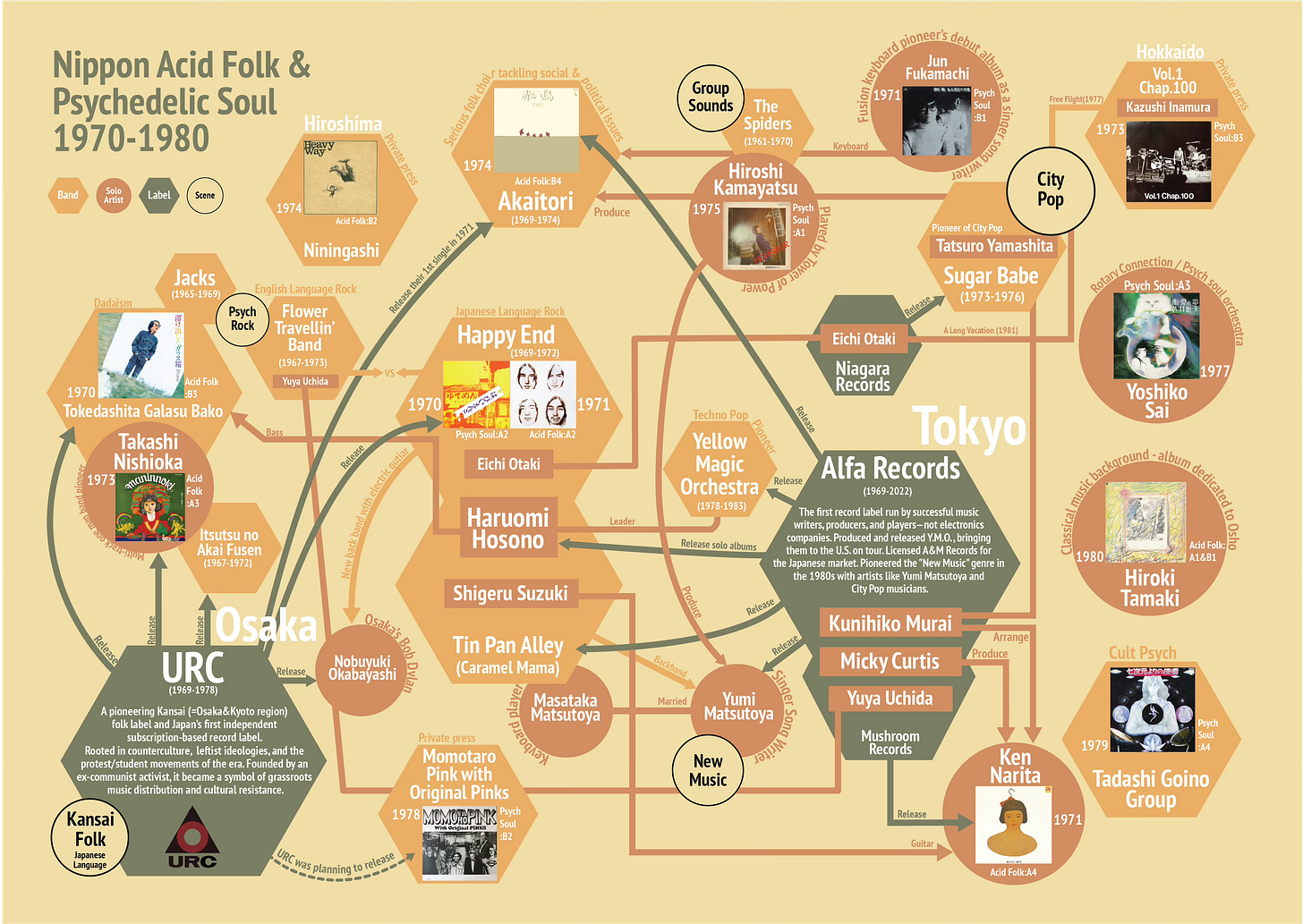

🌀 Nippon Acid Folk & Psychedelic Soul Relationship Map (1970–1980)

This map visualizes the connections between the artists, bands, labels, and scenes featured in our two compilations.

From the acid folk movement centered around Kansai’s URC label, to the psychedelic soul, new music, and proto-techno scenes that took root in Tokyo — it traces how music and language intertwined and evolved across 1970s Japan. Not a map of genres, but of intersections (download to zoom and explore.)

🌿 Continue the journey:

The follow-up to Nippon Acid Folk dives deeper into the forest — Nippon Psychedelic Soul traces the tangled paths of 1970s Japan’s mind-expanding soundscape. Lost grooves, electric reveries, and spiritual drift await. 👇

Nippon Psychedelic Soul: Groove and Hallucination in Pre-Bubble Japan

“Japan Is Entering the 1970s with Self-Confidence Restored and Economy Thriving”. So ran a headline in The New York Times on 5th January 1970, heralding the decade with a sense of unbridled optimism. Japan was entering its fifth successive year of “boom conditions”, becoming the strongest economy …

💡 Paid subscribers perk:

June’s discount code for Bandcamp is just below—thank you for supporting what we do.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Time Capsule to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.