Shaping the Dancefloor: Beauty and the Beat (Part 2/3)

On setting the mood, reading the room, and building a party from the ground up.

How do you build a dance floor that people trust for two decades? One where strangers turn into a community by 4am? In this second part of our interview with the founders of Beauty and the Beat, we explore how Cedric, Cyril, and Jeremy shape the emotional and physical flow of a night—from the clubs that taught them what a party could feel like, to the quiet logistics of speaker lifts and floor sweeps.

We get into DJ structure, set flow, how sound changes perception, and what it really means to throw a night that feels loose but lands with precision. This is where the philosophy meets the dancefloor.

And if you’re curious about what actually gets played—stay with us. We’ll close out this post with a deeper look at the musical arc of a BATB night.

What other clubs shaped your sound?

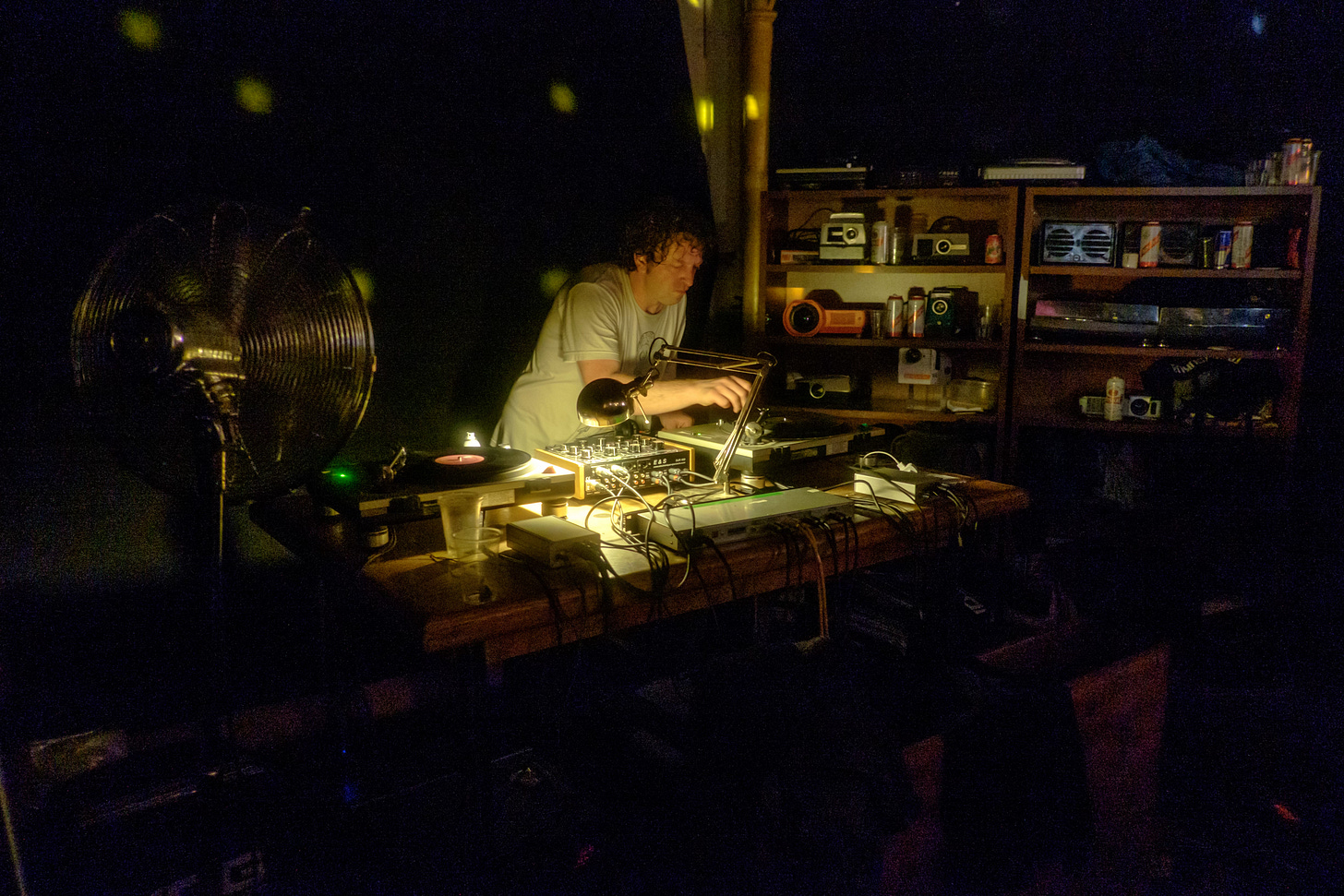

Cedric: Plastic People was like a religious experience for us. We went every Saturday night for years—five, six, seven years in a row. The room was pitch dark, which let you completely lose yourself in the sound. You never knew what would come next, musically.

It was a community-based club. Half the people there knew each other. It was weekly, whereas Beauty and the Beat is monthly, so it was a different kind of thing. But nothing has replaced Plastic People since—it was truly formative.

The Loft (Lucky Cloud Sound System), of course, was also massively influential, though it only happened four times a year. Both places shaped us musically, but also in terms of atmosphere.

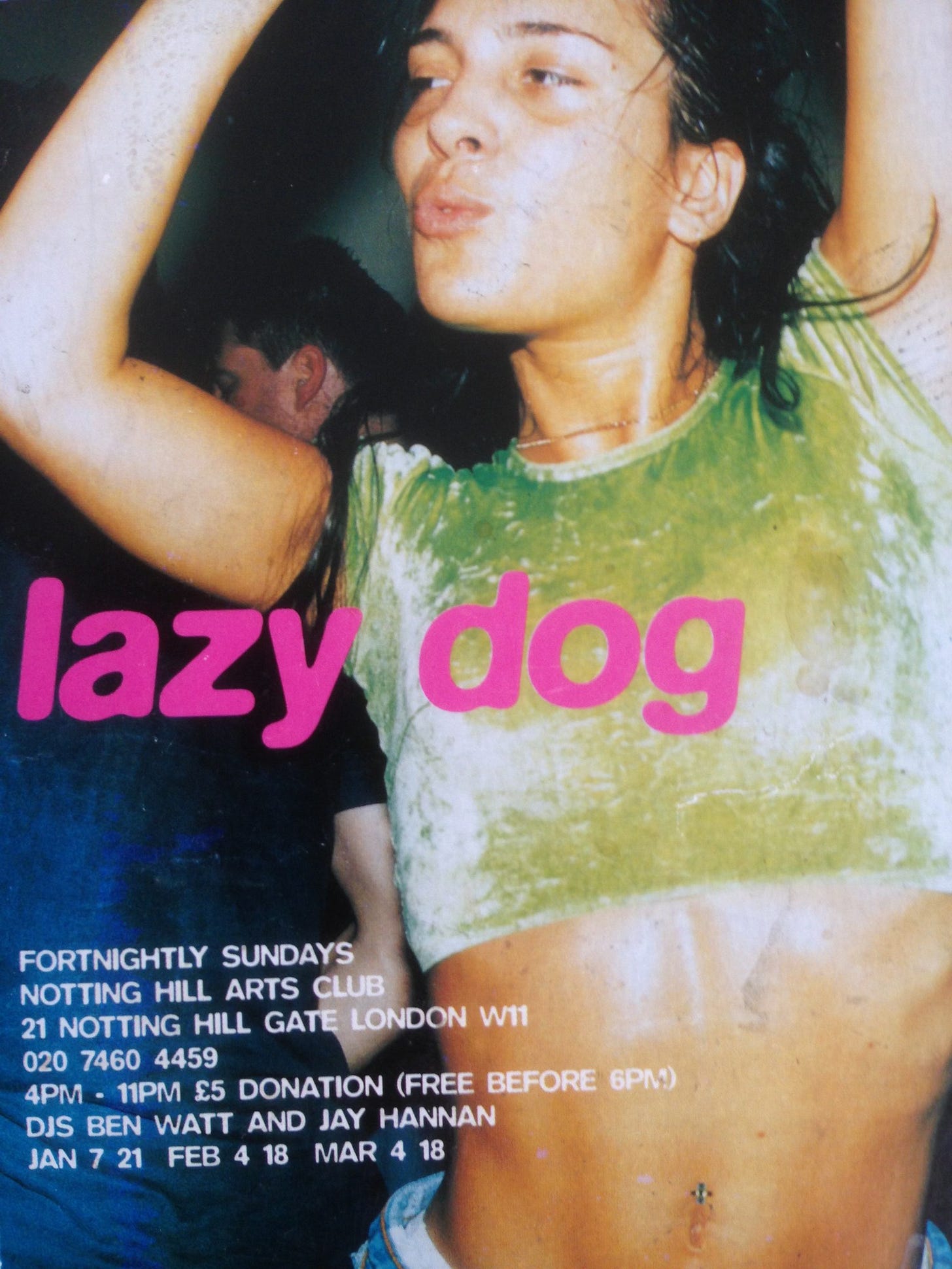

Jeremy: Another important club to mention is Lazy Dog.

Lazy Dog was a Sunday afternoon party at the Notting Hill Arts Club, run by Ben Watt and Jay Hannan in the early 2000s. They were playing deep house—Joe Claussell, New York-style spiritual house—which wasn’t really being played in the "cool" clubs at the time.

In the ‘90s, if you wanted to hear that music, you had to go to Ministry of Sound. But by the late ‘90s, Ministry had become a club for tourists, hen parties, and people coming in from Essex. The real house heads were this tiny group in the corner of the dancefloor, surrounded by stag dos.

I got into that sound by listening to Pleasure FM, a pirate station, and digging for records at Vinyl Junkies in Soho. I loved it—it was jazz-influenced, psychedelic, spiritual house—but there weren’t many good places to hear it. Lazy Dog changed that.

It was a small venue, but they made deep house work in a party setting. It was fun, not overly polished like a lot of London house nights. It was also cheap—five pounds to get in. People would queue for an hour or more just to get inside. You’d take a mild dose of mushrooms, dance all night, and still be able to go to work the next morning.

The funny thing is, Lazy Dog had a terrible sound system. In that sense, it was the opposite of Plastic People. But it had a great vibe—happy, uplifting music, a crowd full of women (which wasn’t always the case in London clubs), and an overall accessibility that made it special.

Cedric: Yeah, Lazy Dog was predictable in a way—you were guaranteed to hear "Finally" by Kings of Tomorrow every week—but that was part of the appeal. It was about good vibes.

Jeremy: Exactly. And even though the music was much more accessible than what we do at Beauty and the Beat, Lazy Dog taught me something important: how to create a party that’s welcoming but still musically adventurous.

That’s always been a key part of Beauty and the Beat. We play obscure records, but the night itself remains accessible. People don’t have to be deep music heads to enjoy it. We learned that balance from years of throwing house parties—playing music that kept us interested but also kept people dancing.

We also learned how critical sound quality is. When you have great sound, you can get people dancing to a 14-minute highlife track from 1978—music they’ve never heard before—because they can actually feel the textures, the rhythm, the energy. If the sound system is bad, those same records just don’t work.

You need the brightness of the guitars, the sparkle of the high frequencies, the warmth of the bass. Otherwise, music that should be hypnotic and powerful just turns into a dull, heavy thud. Sound quality is everything.

How does the day of the party unfold?

Jeremy: The day starts early for us. Before we even get to the venue, there’s a lot of work to do. Until recently, we had to collect all the equipment from different people’s houses—driving around northeast London in a van, picking up speakers and gear before heading to the venue. Once there, we’d spend hours setting everything up. Then, after the party ended in the early hours of Sunday morning, we had to do it all in reverse—packing everything down and driving around again to return the equipment.

In the past year, we finally managed to buy some speakers that stay at the venue, and we’ve arranged to store a lot of our gear there. That’s been a game-changer. Now, instead of an all-day logistical mission, we can arrive in the late afternoon and focus on getting the space ready.

We meet up at the venue with our crew—whoever’s helping that night—and spend about three hours setting up. We’re always grateful for our helpers because, honestly, it’s a real struggle without a team. These days, the doors open at 9 PM, and the party runs until about 4 AM.

Then there’s the breakdown—packing everything up takes another hour and a half, and by the time we get home, it’s been a long but deeply rewarding day.

It’s still a labor of love, before, during, and after the party.

How is DJing structured?

Cedric: We take turns DJing, with three sets each night. The order changes at every party.

The first two hours are all about welcoming people in—setting the mood with gentle, organic music before gradually building up the energy.

Some people say our structure follows the "three bardos" concept, like David Mancuso’s Loft parties. I wouldn’t say that’s entirely true for Beauty and the Beat. At The Loft, the music follows a very intentional, linear structure, whereas our nights have more twists and turns—hills, valleys, and unexpected drops.

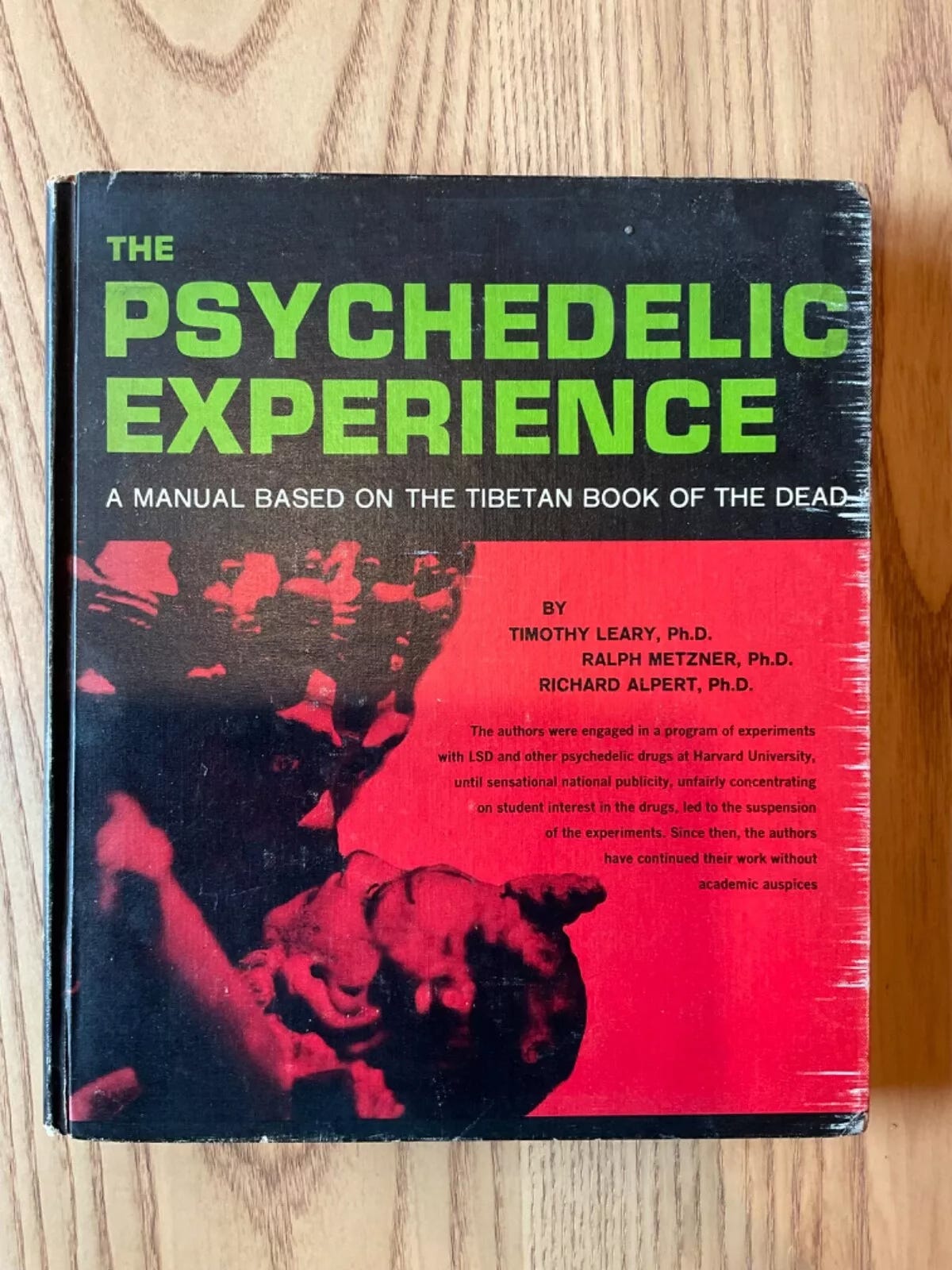

Jeremy: The Loft’s structure is famously based on the "three bardos" from The Psychedelic Experience by Harvard University professors Timothy Leary, Ralph Metzner, and Richard Alpert (a.k.a. Ram Dass). The book itself was inspired by The Tibetan Book of the Dead and describes three stages of an acid trip:

The First Bardo – A state of pure awareness or "clear light."

The Second Bardo – Intense experiences, a "circus" of wild visions.

The Third Bardo – "Re-entry," where you come back down and reintegrate.

David Mancuso adapted this idea to describe the musical journey of a Loft party, but even his approach wasn’t strict or formulaic. Sometimes he’d play for 48 hours straight, and the arc would unfold naturally.

At Beauty and the Beat, we don’t really follow this model in a strict way, but there is a loose sense of progression.

Cyril: At the start of the night, people are arriving, maybe having their first drink. You need a lot of groove—something percussive, not too fast, not too slow—to get people moving.

The middle of the night is more of a peak-time set, but even then, it’s not predictable. We might throw in a roots reggae track in the middle of peak time, and people will love it.

The last set is where things can get really deep and exploratory. The people who’ve stayed until the end are usually the most dedicated dancers, so we can take risks—playing more experimental or cosmic records.

How has the approach to structuring sets evolved?

Jeremy: It’s changed over time. In the early days, the "warm-up" set was more obvious because the room wouldn’t be full until later. That’s not the case anymore—within an hour or two, there’s already a big enough crowd to create a strong energy.

Each year, our audience becomes more musically adventurous. There are fewer records that "only work in the last hour"—people are more open to hearing deep, obscure tracks earlier in the night.

Cyril: We don’t plan our sets in a rigid way. There are always a few records we know we’ll play at some point, but most of it happens spontaneously.

It’s about reading the room—if the crowd feels deep early on, we go deep. If they need more energy, we adjust. Some nights, you can drop a 12-minute live Pharoah Sanders track at midnight on New Year’s Eve—where else can you do that?

Cedric: Every night is different. Sometimes, the vibe is deep from start to finish. Other times, it takes a while to get there. The unpredictability is part of the magic.

Over the years, we’ve built our own set of "Beauty and the Beat classics". Of course, we draw from The Loft and Plastic People, but we’ve also created our own core records—tracks we might drop every few parties, or a whole set of them if it’s our anniversary or something.

But we’re always bringing in new records too—songs that have never been played at the party before. That balance keeps it fresh.

To close this chapter, we asked them to select 10 records that capture the emotional arc of a BATB night.

🪐 The full list—with notes from the selectors—is available to paid subscribers below along side with April’s 15% discount code for our bandcamp page.

Most of photos are taken by Miguel Echeverria.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Time Capsule to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.