So-Do: Post-Punk Idealism and Disillusionment in Bubble-era Japan

So-Do’s Studio Works ’83-’85 collects the full output of this iconoclastic phenomenon, whose sparse, dubbed-out sound painted the disenchantment of 80s Japan in ice-cold style.

Talking Heads had CBGBs, Sex Pistols had the Roxy. And So-Do had Buddha. Small venues might have sustained independent music in other countries, but in Japan in the late 1970s, the concept of the ‘live house’ was still relatively new. Alongside freshly minted independent labels and student-led collectives, they played an important part in what was a burgeoning alternative music scene. A ‘live house’ was essentially Japan’s answer to the grungy basement club, a place where bands played sweaty shows to standing crowds and communities were given the freedom to coalesce away from the commercial, conservative demands of the mainstream. In Tokyo, the Shinjuku Loft and S-Ken Studio in Roppongi were crucial to staging the country’s nascent punk movement. In Kyoto, the key spots were TakuTaku and Jittoku. And in the mountain town of Nagano, 230 km outside Tokyo, Buddha was the place to be.

Buddha was the first establishment in Nagano to call itself a ‘live house’. It was 1975 and 22-year-old Atsuo Takeuchi had just returned home after a stint in Tokyo and was looking for something to do. Like his musical heroes at the time, he styled himself in the spirit of a rolling stone, with rakish hair and a love for West Coast psychedelia. “I was travelling around, being a hippie and was in the counterculture,” Takeuchi remembers. “And I wanted to hear more music, so I thought the best way would just be to open a space.” On a narrow street, on the second floor of a building between the cinema and the city library, Buddha was born. Within a year, what began as a ruse for Takeuchi to listen to the Grateful Dead records he'd brought back from California became a hub for the city’s young and vibrant rock scene, a place where college kids skipped school to hang with dropouts and dreamers, and hear new music played by bands they’d never heard of and might never hear of again.

Hideshi Akuta was one of those dreamers. A musical child who’d been pushed towards classical violin by his parents, Akuta was in high school when he first heard Bob Dylan, beginning a love affair with folk and rock music that spanned everyone from The Band and King Crimson to Pink Floyd and Yes. But having failed to secure a place on a music course at university playing clarinet, Akuta found himself kicking around in Tokyo, going to poetry readings, playing acoustic guitar and figuring out what to do next. Like Takeuchi, that meant returning home to Nagano.

And like Takeuchi, Akuta had fallen for hippy culture in a big way, growing out his hair, wearing tatty clothes and trailing his acoustic guitar around town, acting out a fantasy that was increasingly at odds with his daily reality in which he was married at 23 to his middle school sweetheart and working as a delivery man to support his family. Such was the lot of the small-town troubadour.

A regular at Buddha, Akuta began to be invited to play guitar with local bands, and it was in that same room where he met guitarist Asahi Tsukuda, bassist Yoshifumi Ito and drummer Kimihiro Takemae, who would go on to become So-Do. In 1982, the band formed, catching the new wave of alternative music in the early ‘80s, listening beyond the psychedelia and folk of hippy subculture and towards the more hybrid post-punk sound of urban centres like London, Berlin and New York. The first event they played together at Buddha was called ‘Newcomers of Rock Music’, but rock music in no way did them justice.

Instead, Akuta was being increasingly drawn to the reggae he was hearing on Takeuchi’s sound system at Buddha. Bob Marley had toured Japan in the late ‘70s, and as featured on Time Capsule’s Tokyo Riddim compilations, J-reggae fever was sweeping the country. Attracted to the political message of the music and the sparse rhythms which would allow space for his introspective lyrics to breathe, Akuta and So-Do began to cut their crisp new wave licks with a backbeat that had more in common with the Dennis Bovell-inspired productions of Orange Juice, the Jah Wobble basslines of Public Image Limited or Gang of Four’s punk-funk attitude than even they knew at the time. In dark glasses, parkers, white shirts and braces, So-Do oozed post-punk cool, and in Hideshi Akuta they had a multi-instrumentalist and songwriter who could capture the zeitgeist with a turn of phrase or a honk of sax and transform it into something entirely their own.

Buddha was more than just a stage for So-Do to perform on. A fan of the UK dub’s sparse edge, Atsuo Takeuchi had devoured the music of Linton Kwesi Johnson and Matumbi, and eventually took himself to London to hear Adrian Sherwood live dub The Pop Group’s Mark Stewart to a room full of punks and rastas. Stationed behind the sound desk at Buddha, Takeuchi played his role well, actively infusing So-Do’s live shows with his own nascent dub mixing skills, helping the group iterate and arrange tunes over time with an experimental attitude that only a small independent venue could offer.

When Akuta said he wanted to record and release the music they were playing at Buddha, it was clear that Takeuchi would be their de facto producer, even though neither had done anything like it before. And so, in 1983, they booked a studio with an 8-track desk in the Tokyo suburb of Saitama and cut the 7” single ‘Natural Wave’ / ‘SO-DO Theme’. After a year spent touring the live houses of Japan, they were back in the same room for a second 7” that featured ‘Kakashi’ / ‘Hashiru’. So-Do were a salary man band living out their destiny on the weekends and embracing the rip-it-up-and-start-again ethos of the early ‘80s in the process.

It was a tension of which Akuta was all too aware. Scan the lyrics of ‘So-Do Theme’ and the internal struggles of its songwriter are crystal clear. For Akuta, music was an escape, for both body and soul, from the existential malaise of small town life in ‘this cramped place called Japan.’ Folded into ‘Kakashi’ and ‘Hashiru’ (which translates as ‘run’) is a melancholy nihilism, the thwarted desires of a once idealistic spirit, worn down and disillusioned by the empty promises of boom-time capitalism. ‘But I keep running,’ Akuta sings with defiant, defeated anger on ‘Hashiru’, ‘Running harder, running strong / Everything around me fades / Time creaks as I run.’

Although So-Do were playing upwards of thirty gigs a year, their progress into the more formal realms of the Japanese music industry were hindered by the material conditions of the band’s members, some of whom could not imagine giving up their day jobs to tour more regularly or take the major label deal they were once offered. And yet, for their third single, Akuta and Takeuchi aimed high, booking time at a studio in Omori, Tokyo and cutting four tracks to a 12” record that would turn out to be their last. Engineered by Minoru Inaguma, it included guest musicians Osamu Tsukaoka, Gen Ogiimi, and Yasuo Imase, who bulked out the sound on ‘Get Away’, ‘Scrambled Eggs’, ‘Nothing’, and ‘Morning’, and helped give So-Do a professional sheen that concealed their humble origins.

“I don’t say big things, but only what I can say from my personal point of view,” Akuta explains of his approach to songwriting. “I always had the feeling that I can only express what I’ve experienced.” The lyrics to ‘Get Away’, which opens this compilation, bear this out most keenly. ‘Poverty, all for sale / Madness, all for sale / Peek behind the scenes, and you'll find price tags there / BABY, RUN AWAY. BABY, GET AWAY,’ he sings, troubled by the inequality and the ennui that he witnessed all around. ‘Nothing’ meanwhile reflects on the creeping apathy of middle-class life: ‘No war, but no peace / Not wealthy, but not poor / Not something I love, but not something I hate, either / My years keep adding up, just living day by day.’ Delivered with a punkish, spoken word flare and set against syncopated, often playful melodies, Akuta’s lyrics were, like so many of the best post-punk orators, both acerbic criticisms of a corrupting society and knowing self-deprecations of his own failure to escape it.

As 1985 ticked into 1986, Buddha bar shut its doors for the last time, and with the decade’s early optimism on the wane, Akuta and So-Do decided they too had run their race, only to find themselves back exactly where they had started. There was a future once, but it wasn’t today, and it might not be tomorrow either.

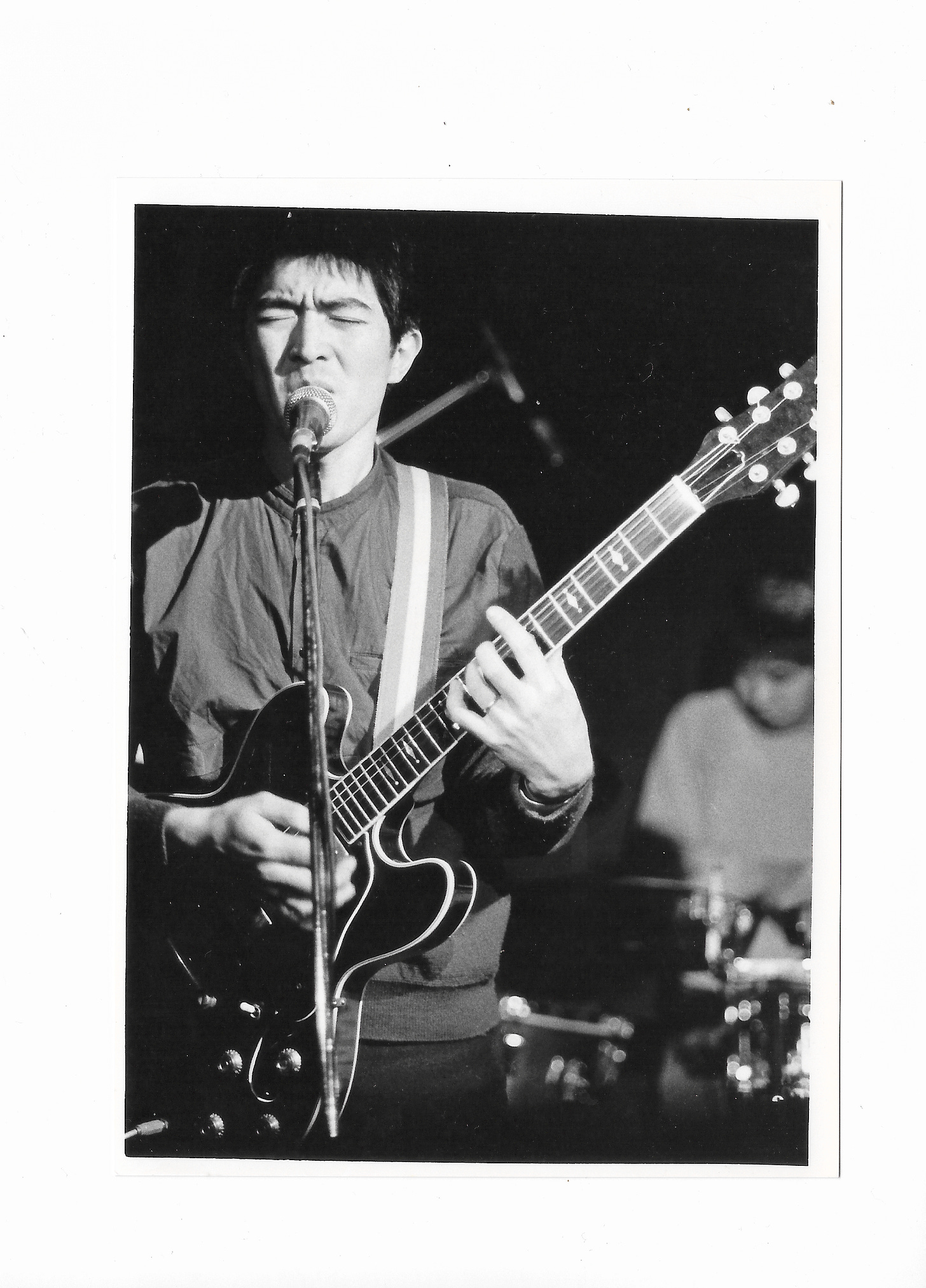

In a sense, the story of So-Do is the story of a thousand unknown indie bands. Bands who channelled their hopes and dreams into music, whose star burned brightly for a short time, and who then returned to their lives with little more than a handful of black and white photos, a few self-released recordings and a shoebox of memories to show for it. Although So-Do went through several line-up changes and Akuta continues to perform with Ryuichi Masuda and Kimihiro Takemae as So-Da, the band’s original legacy is neatly tied up in three singles, released in three years between 1983 and 1985, and produced by the man who ran the club where they played their first shows. It is this era that Studio Works ’83-’85 revisits and which makes So-Do one in a thousand unknown indie bands who forty years on are about to reach a new, international audience unlike any they could have imagined.

As for Atsuo Takeuchi, you could say that the story of his live house Buddha is the story of a thousand small music venues too. Crucial, utopian, overlooked spaces that manifested their owner’s deepest held desires to share music with the world and support local musicians in places like Nagano whose population of little more than 200,000 had, for a short time in the 1970s and ‘80s, something like a counterculture to call their own. What this is truly worth is difficult to say. “So-Do is hard to explain,” Takeuchi muses. “It’s been a struggle for years to try to find the words for our music.”

Perhaps that is because although the scaffolding of these stories is familiar, the specifics are always unique. A classically trained multi-instrumentalist with a poet’s sensibility and a passion for folk music meets a worldly bar owner with a love for psychedelia, post-punk and dub in the town neither could bring themselves to leave. Over nights spent jamming and listening to music, they hone a sound that captures the turning mood of bubble-era Japan as glimpsed from beyond the big city – threaded with influences they can’t quite name and emotions they haven’t quite processed. They make three records, they tour, they return home, and before they know it, the thing they created is a thing of the past and all they have left is the feeling that they did what they could until life moved on and the music stayed behind.

Atsuo Takeuchi now runs a venue called Oregano Café in Nagano and plays records to customers using the same turntable he had the day Buddha opened in 1975. As for Buddha, it remains a live house of sorts, a music venue called Neon Hall, to be found on the second floor of a building on a narrow street, between the cinema and the library, concealed by a wall of ivy now so thick you can barely read the name on the sign, and behind whose door a whole lot more history happened while no-one was really looking, much of which is still waiting to be told.

Anton Spice

Looking forward to this release... I only have the second 45... knew none of the back story... fantastic read...

This is spectacular. Post punk from Japan is always something I’m trying to find out more on. It’s great to know it’s there to be found if I look in the right places!