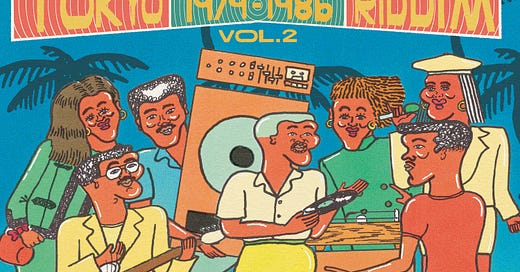

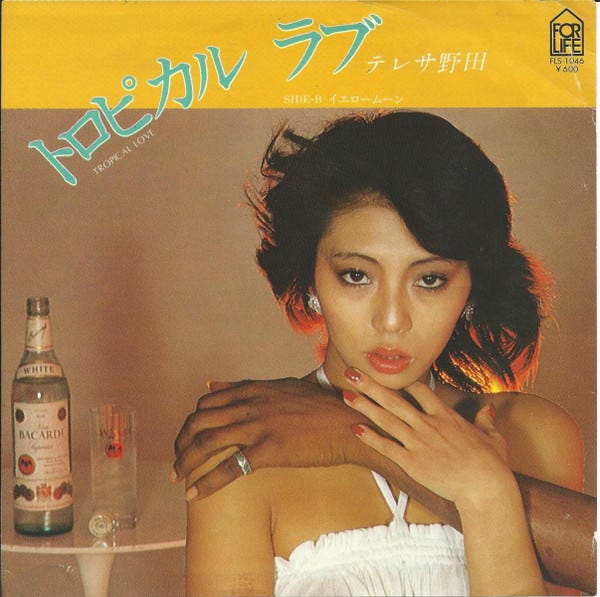

Tokyo Riddim 2: Digging Deeper into Outernational Sounds

The second instalment of the Tokyo Riddim series explores an electronic, new wave and often experimental sound unlike anything Japan or Jamaica had ever heard before.

It is 1980 and Don Letts is catching up with dub innovator Dennis Bovell in London. Letts has just returned from a tour of Japan with Big Audio Dynamite, with news of a possible collaboration for Bovell. “Some guy that plays keyboards wants to get in touch with you,” Letts says. “Who is it?” Bovell replies. A pause. “Ryuichi Sakamoto … Can I give him your number?”

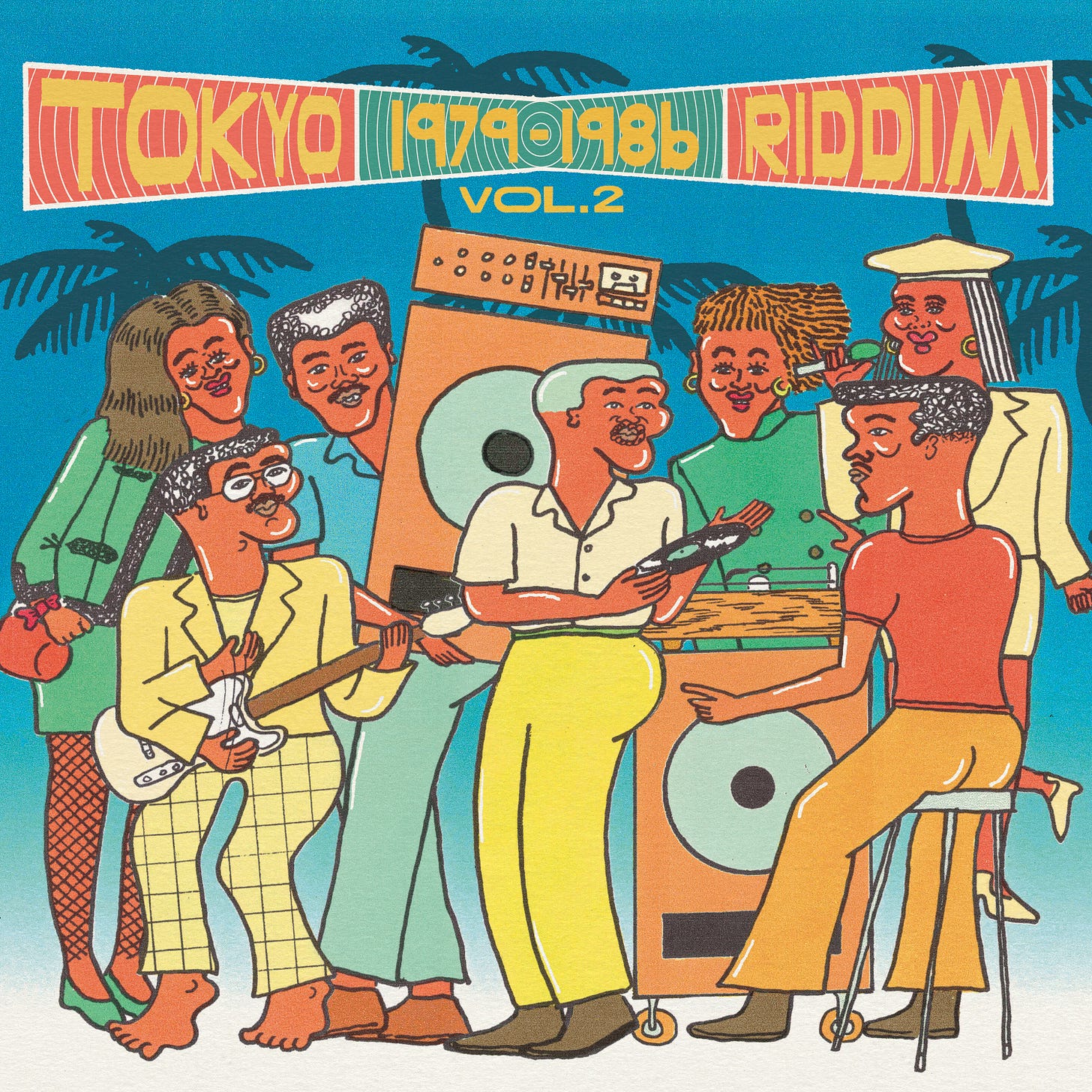

Even in recounting the story on NTS in 2022, Bovell can’t quite believe how it all went down. Sakamoto had been in Germany recording at Kraftwerk’s studio and wanted to ship some gear over to London, even though Bovell’s studio wasn’t quite finished yet. “I’m thinking oi oi, this is not sounding right. He’s a top Japanese composer, he’s got his equipment in Germany … and he says he wants to use my recording studio before I do?” Already a big Yellow Magic Orchestra fan, Bovell didn’t need to be persuaded.

The track Sakamoto ended up making was ‘Riot In Lagos’, sketched out on manuscript paper to be cut up and dubbed out by Dennis Bovell, and included on Sakamoto’s 1980 solo album B2-Unit. Released into a rapidly globalising Japanese economy, it captured the borderless flows of musical influence that were accelerating into the new decade. Japan, Germany, Jamaica, London, Lagos - all were represented. Sakamoto in the centre, a self-proclaimed outernational orchestrator. A connector of worlds, a believer in utopias

Ryuichi Sakamoto was 26 when he first left Japan - not for the United States, the UK or Europe, but for Jamaica. The year was 1978, and reggae was already beginning to infiltrate Japanese pop, smuggled in via the cod sound of bands like The Police and UB40, whose rhythmic appropriation of Jamaican music chimed with the Japanese music industry’s deference to Western musical trends and a desire to be titillated by that which seemed exotic. As was explored in the first volume of Tokyo Riddim, an unobtrusive backbeat was like catnip to the commercially savvy city pop producer, who might slip a little reggae into an album track to satisfy both the worldly listener and the label’s bottom line.

For the man they called the “professor”, this second-hand experience of the music evidently wasn’t going to cut it. “I really wanted to see the movements of local musicians in person,” Sakamoto explained, when asked about his early exposure to reggae in a GQ interview in 2021. Initially resistant to music that seemed so far from his compositional training, in another interview, he expanded further. “Reggae is a simple music, but I discovered that within its deep forest of sounds lies a surprisingly complex landscape. But that complexity is never easy to reveal.”

In November 1978, Sakamoto was invited by producer Kazahiko Kato to sit in on a unique and unusual session. Yellow Magic Orchestra were on the cusp of releasing their debut album, but Sakamoto was touching down in Jamaica for the first time, ready to have his mind blown.

"The moment I got off the plane in Kingston, Jamaica, on my very first trip abroad, I was hit by a series of intense culture shocks,” Sakamoto explained in a magazine interview the following decade. The cityscape, the food, the culture. He was mistaken for Chinese at the airport, felt the kinship between Jamaica and the African continent (which he was also yet to visit) and was shocked to find that none of the musicians he encountered could read scores, as he had been accustomed to in Japan. “I never met an engineer [or musician] who asked for or could read sheet music,” he explained, again to GQ. “However, they had an incredible memory. They could remember an entire new song after hearing it just once.”

The studio Sakamoto found himself in was the iconic Dynamic Sound, which was owned by Byron Lee and known for recording likes of Toots and the Maytals, Max Romeo and now perhaps most famously, Chaka Demus & Pliers’ ‘Murder She Wrote’. Back in the late ‘70s, when international artists like Paul Simon, Eric Clapton and the Rolling Stones came to Jamaica they too would record at Dynamic Sound.

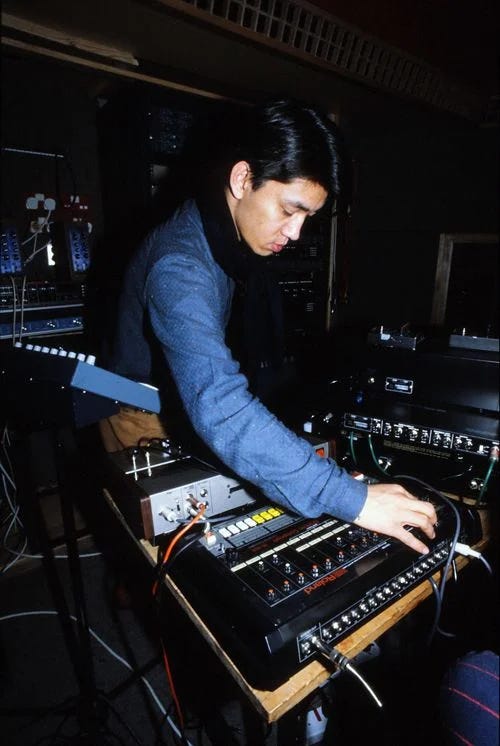

On the surface at least, this session was a little different. A child star-turned-swimsuit model and idol singer, Teresa Noda was lined up to cut her third and final single on For Life Records. The tracks that would become ‘Tropical Love’ and ‘Yellow Moon’ were to be recorded in between Kingston and Miami. Typical of an industry flush with cash and big ideas, the project was sponsored by Bacardi (a bottle of which sits open behind Noda on the 7” sleeve, and is name-dropped in both tracks) and brought together some of Jamaica’s finest session musicians. Michel Richards (drums), Val Douglas (bass) and Alvin Haughton (percussion) were joined on the piano by Neville Hinds. Mike Mao Cheung and Willie Lindo shared guitar duties. Rita Marley was on backing vocals. Ryuichi Sakamoto on synths.

To borrow Sakamoto’s phrase, there is something outernational - something utopian - about this scene, not simply for its improbability or for the impact it would have on Sakamoto’s own music in the coming years. In connecting the dots between Tokyo and Kingston, between Jamaica and Japan, Sakamoto and the broader J-reggae sound was building a musical language that existed outside of the paradigms of US and European cultural hegemony – cutting a new course across the world that resisted and decentred the West altogether. It is an example of what academic Marvin D. Sterling has called “Afro-Asian encounters”, traced through the tracks on this compilation to the modern day, and the enduring popularity of reggae in Japan.

For Sakamoto, the Teresa Noda session (which opens and closes this volume of Tokyo Riddim) marked the beginning of a journey that would see him release Summer Nerves in 1979 - his own chirpy reggae-pop record with an electro-futurist twist, all vocoders and backbeats, featuring the joyous ‘Sleep On My Baby’, written and subsequently also recorded by Akiko Yano. And it was the start of the journey that would bring him to Dennis Bovell’s door the following year to make ‘Riot In Lagos’ – a track that drew so many threads together as to make the geographical dichotomies often attached to his work completely irrelevant. Because, as he would ask musician and writer David Toop years later, if there was such a thing as East and West, “where is the edge?”

Teresa Noda / Tropical Love & Yellow Moon

There are some releases the significance of which only become apparent over time, for both their unforeseen alchemy and the meeting of stories and trajectories that coalesce around them. The brainchild of pioneering producer Kazuhiko Kato, who played a defining role in the ‘60s bands The Folk Crusaders and Sadistic Mika Band and was central to the “new wave reggae” sound of the late ‘70s, the Teresa Noda 7” which bookends this compilation is one of them. Introduced to reggae by Malcolm McLaren in London, Kato assembled something like a super group for ‘Tropical Love’ and ‘Yellow Moon’, whose studio session at Dynamic Sound in Kingston felt like a thing of dreams. Rita Marley on backing vocals, Ryuichi Sakamoto on synths, Neville Hinds on piano, compositions by Kato himself.

For her part, Noda carries both tracks with quiet and naïve aplomb, a fitting and breezy vocal lead that treads so lightly it almost seems to dissolve completely into the warm Caribbean night. That the single was released on For Life Records – an independent label founded by four leaders of the folk movement, Hitoshi Komuro, Takuro Yoshida, Shigeru Izumiya and Yosui Inoue (from whom we’ll hear more of next) – also spoke to the radical undercurrent to the release, giving artists and producers more rights over their recordings than would be possible within the constraints of the mainstream Japanese music industry.

‘Tropical Love / Yellow Moon’ was the last of three singles Noda released on For Life, but stands now as a marker of so much more in the development of Japanese reggae as a collaborative and idiosyncratic sound in its own right.

Yosui Inoue / Anata Wo Rikai

In 1967, a young Yosui Inoue was at university trying and failing to pass his dental exams when he came across a song called ‘The Drunk Man is Back’ by Kazuhiko Kato’s the Folk Crusaders and promptly resolved to quit his studies and become a musician. Struggling to build a reputation through the late ‘60s, it would take until 1973 and a series of outings for Polydor for Inoue to break through to nationwide success. Ten years and almost as many albums later, Inoue released Ballerina, from which “Anata Wo Rikai” is taken. Produced by Yuji “Banana” Kawashima (who was also part of Kyoto no wave band EP-4) the record embraced the pan-global influences that were sweeping through Japanese new wave in the early ‘80s, drawing on dub, afrobeat and a kind of electro-Balearic sound on the way to becoming one of Inoue’s least successful but most adventurous projects. On “Anata Wo Rikai” there is a rawness and a depth to the production that has more bassweight and madcap sonic experimentation than many of the city-pop reggae tracks that were being pumped out at the time.

Juicy Fruits / Oshiete Ageru

Like many bands of the era, Juicy Fruits were a product of the rapidly changing musical landscape in Japan, comprised of musicians who abandoned their musical roots to reform as punk and new wave groups, with new haircuts and wardrobes to match. The group was initially produced by Haruo Chikada (who also produced Miki Hariyama’s two tracks on Tokyo Riddim Vol. 1). Taken from Come on Swing, the group’s sixth album in four years, “Oshiete Ageru” glides with the smooth double time feel of Grace Jones’ ‘Walking in the Rain’, and is the perfect example of how the clean-cut the Compass Point Sound influenced much of Japanese reggae’s more sonically adventurous offerings.

Yuki Nakayamate / 3 -Trois-

Juicy Fruits weren’t the only outfit on this compilation to be heavily influenced by Grace Jones and Compass Point. A successful backing vocalist with renowned singer-songwriter Sano Motoharu, Nakayamate’s solo career was cut short by illness, bringing forth just two albums between 1981 and 1983, both of which were signed to US disco label Casablanca, who were expanding into new markets to offset the decline in popularity of their classic disco diva sound. Written by Kyohei Tsutsumi, one of J-pop’s most recognizable hit-makers (who is said to have composed 3000 songs and sold over 75 million records), the second album was called Octopussy, and was conceived in the trope of a Japanese disco noir – a sultry, low-lit spy soundtrack, named after a James Bond film, with Nakayamate as the mysterious femme fatale on its cover. Referencing Grace Jones’ ‘I’ve Seen That Face Before’, it made the most of Nakayamate’s deep voice, whose sophisticated delivery held the tension between spoken word and sung vocals with consummate precision.

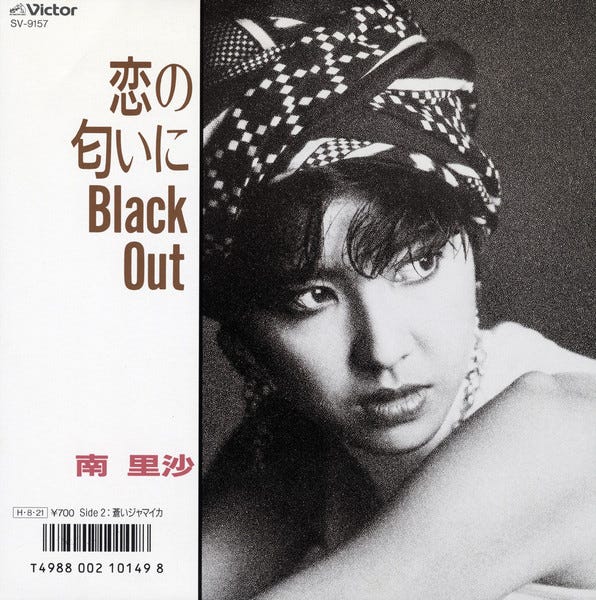

Risa Minami / Blue Jamaica

There are many ways to read the career of the artist known as Risa Minami. Born in 1965 as Harumi Kamo, she made her musical debut as the singer of animé ‘TokimekiTonight’, before changing her name first to Risa Minami and then Harumi Natsuki. Following a pattern familiar to many industry artists whose path was set by major labels from animé to idol, Minami struggled time and again to break through to wider audiences. While the reggae influence on the 1986 Shirou Sagisu-produced track ‘Blue Jamaica’ – with its unconvincing lyrics (exhibit 1: ‘I love Jamaica, it’s a paradise’) – feels misplaced, there’s something peculiarly compelling (and undeniably groovy) about its superficiality, a plastic souvenir of an island Minami likely never visited, that says more about mid-‘80s Japan than it ever would about Jamaica.

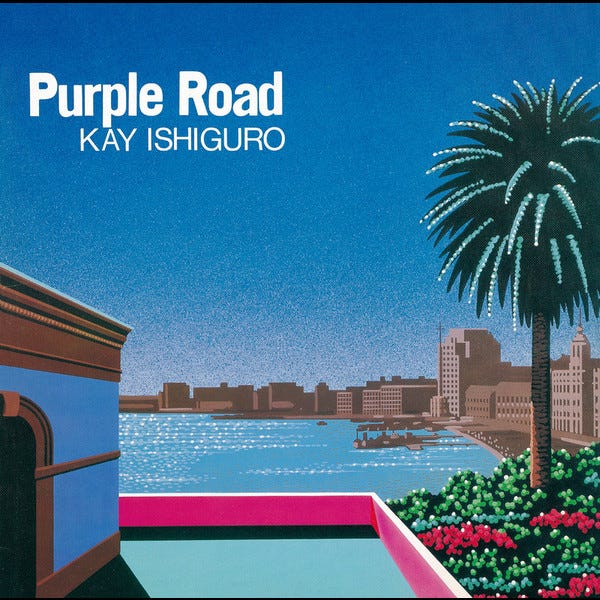

Kay Ishiguro / Red Drip

There were no such career struggles for Kay Ishiguro, the jazz and pop singer from a musical family whose prolific but relatively short-lived recording career heard her debut in 1977 on a record produced by Kyohei Tsutsumi (who wrote Yuki Nakayamate’s Octopussy) before going on to record with US jazz elders Art Pepper, Charlie Rouse, Cecil Bridgewater and Benny Carter. The record that gives us ‘Red Drip’ was called Purple Road and was similarly ambitious – a huge cast of Japan’s finest session musicians, that featured among others a percussive contribution from Pecker, whose albums Pecker Power and Instant Rasta were among the first and most influential Japanese reggae records to be cut in Jamaica. There’s a touch of Stevie Wonder to the instrumentation, a soft rock guitar solo to die for and an in-the-pocket backbeat, given that extra little city pop sheen by the album’s Hiroshi Nagai-designed cover.

Tomoko Aran / Kanashiki Vaudevillian

Singer and lyricist Tomoko Aran’s 1981 debut album Shinkei Suijaku was the first of nine she cut for Warner Brothers throughout the 1980s, but it was a track from her 1983 album Fuyü-Kükan that is perhaps best known outside Japan, sampled by The Weeknd on his 2022 single ‘Out of Time’. Although she might not be a household name, the musicians she recorded her debut with now are. Produced by Yasuaki Shimizu and backed by Shimizu’s band Mariah (who have also been extensively reissued in recent years), the record shimmers with experimental intent. A low-slung ballad that twists a loping reggae rhythm section into a new wave leftfield pop track, ‘Kanashiki Vaudevillian’ emphasised just how much a Jamaican reggae influence was used in a palette of sounds by open-minded producers, at this point really quite far removed from the original intent of the music it was referencing. In their own way, doing very much their own thing, Tomoko Aran and Mariah are prefect examples of the fluid and hybrid utopia that Ryuichi Sakamoto talked about for his own music – a friction between Jamaican and Japanese musical sensibilities that were rubbing up against one another in unexpected ways and producing music unlike anything either island had heard before.

Anton Spice

also shoutout to the artist noncheleee (cover art artist) blessing amazing artwork from the underground to overground

Had no idea bout Summer Nerves, definitely going to see if I can find that one sometime!