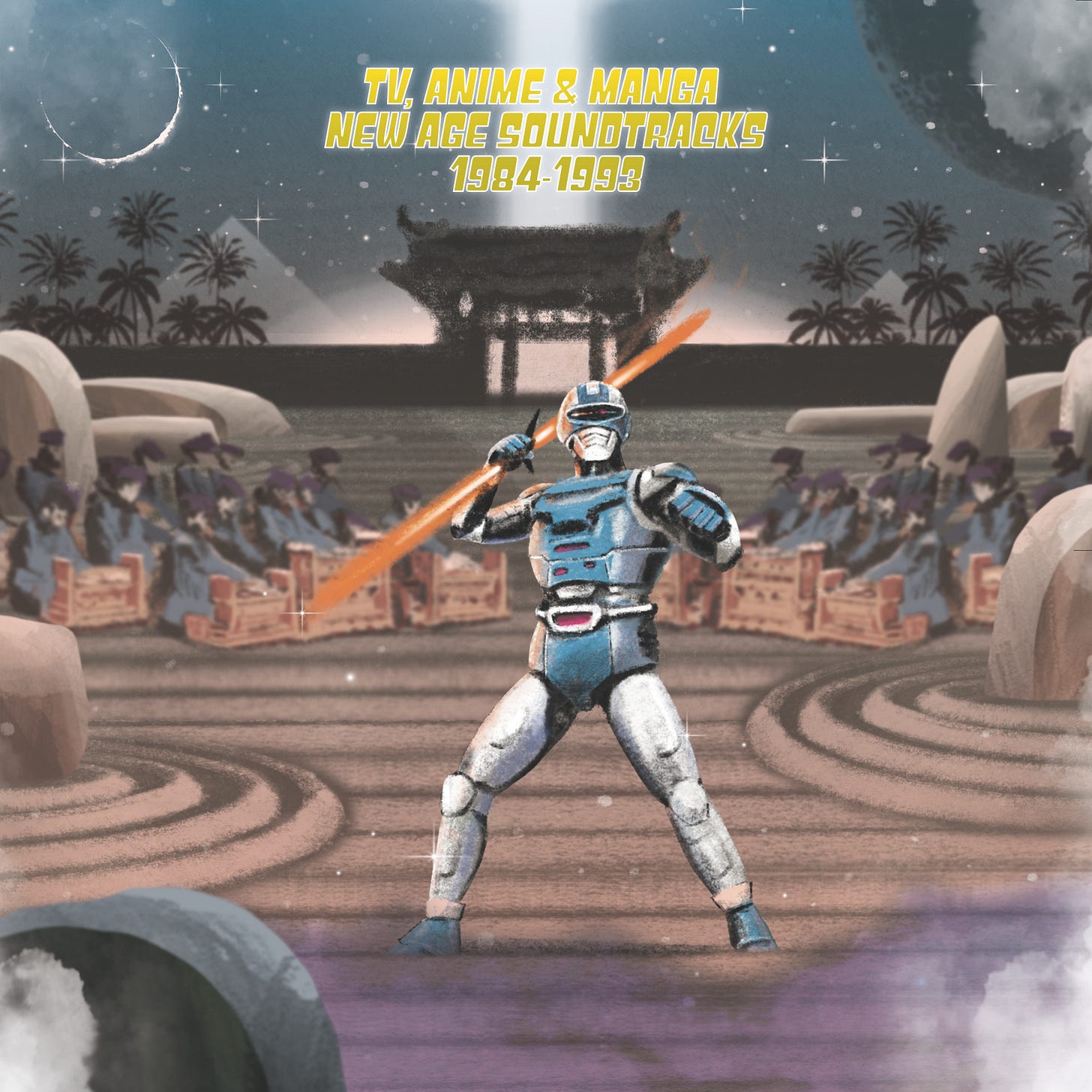

TV, Anime & Manga New Age Soundtracks: Mysticism and High-Tech Fantasy in an Era of Affluence

Journey through the dreamlike sound worlds of new age Japan during the visionary anime boom.

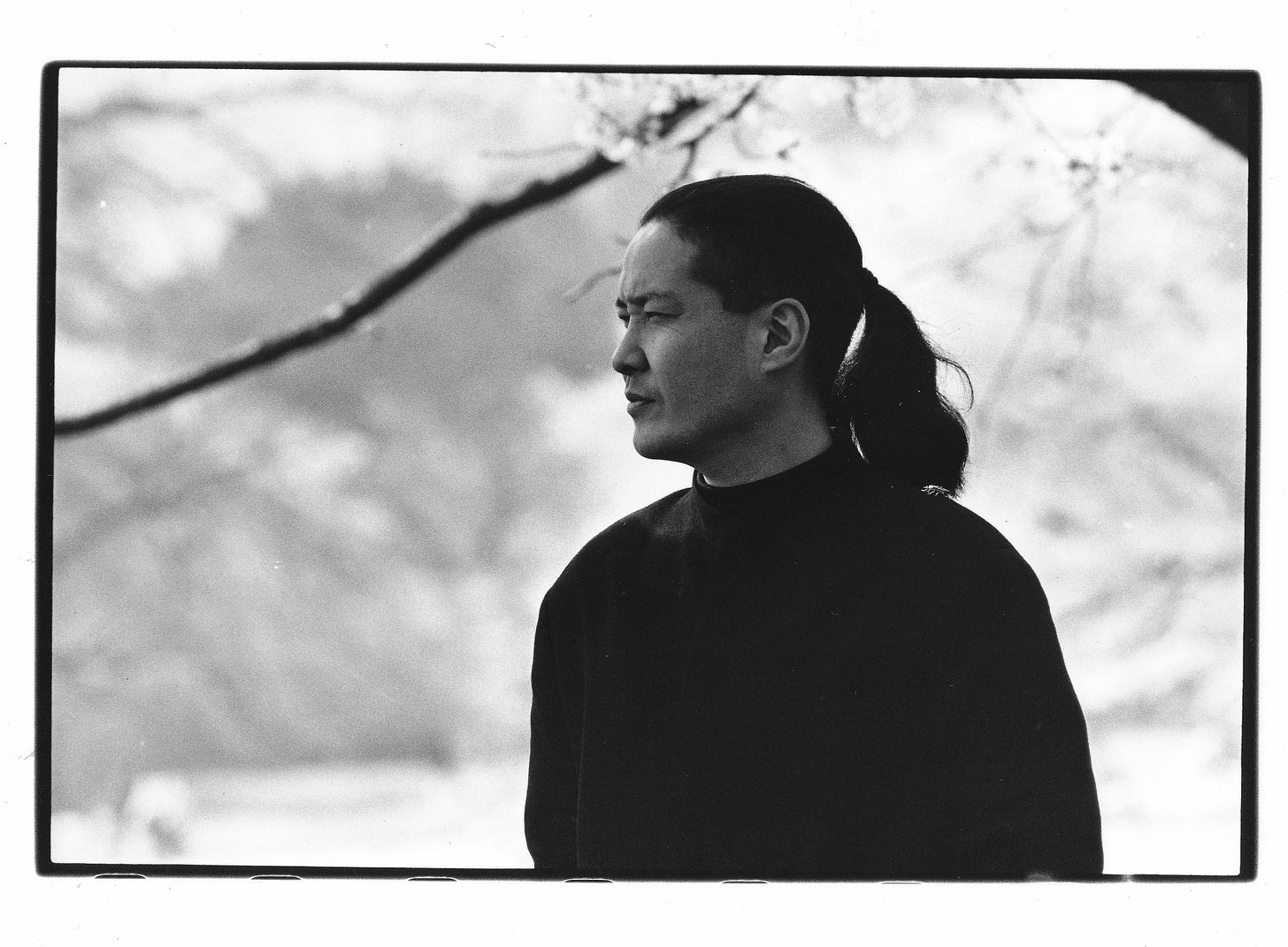

When Japanese composer Yas-Kaz left Tokyo for Bali in the mid 1970s he had little idea of how influential his trip would become. A graduate in percussion from the Tokyo University of Art, Yas-Kaz had found a home as a drummer on the city’s underground free jazz scene and revelled in its multi-disciplinary milieu. Alongside his work as a percussionist, he became fascinated with the post-War avant-garde dance of Butoh, composing music for a then newly formed dance troupe called for Sankai Juku who would go on to gain international acclaim.

In a sense, the emergence of Butoh as an art form reflected a country in transition. Born in part from a reaction against what was perceived to be too great a fixation on Western dances such as ballet, early Butoh choreographies were knowingly iconoclastic and experimental.

It was in this spirit of restlessness that Yas-Kaz struck out to Bali, intent on learning the art of Balinese gamelan music. A complex and regionally specific form of ensemble music involving the playing of resonant percussive metallophones, gamelan often accompanied religious and social ceremonies, and had resonated with musicians from outside Indonesia for several generations. As Western composers looked to the East for spiritual enlightenment in the 1960s and ‘70s, gamelan found its way into the works of John Cage, Steve Reich and Philip Glass. On 1969 album Eternal Rhythm, Don Cherry incorporated gamelan into his nascent vision of borderless “organic music”.

For Yas-Kaz however, gamelan was a way not of measuring up against Western trends, but of side-stepping them completely. Speaking about his 1985 album Jomon-Sho, which was produced for the Sankai Juku dance troupe, he said: “I feel that I am re-experiencing the many histories of music existing in the world, such as the beginning of sound. I find richness in instruments and in the sounds that modern music and Western music has left behind.”

Having returned to Japan, Yas-Kaz spread the gospel of the gamelan, introducing it to Midori Takada, herself pursuing a form of pan-global minimalism with her MKWAJU Ensemble, Ryuichi Sakamoto, with whom he would go on to make the richly textured 1985 album Esperanto, and Shouji Yamashiro, whose adoption of gamelan would arguably have the biggest impac all.

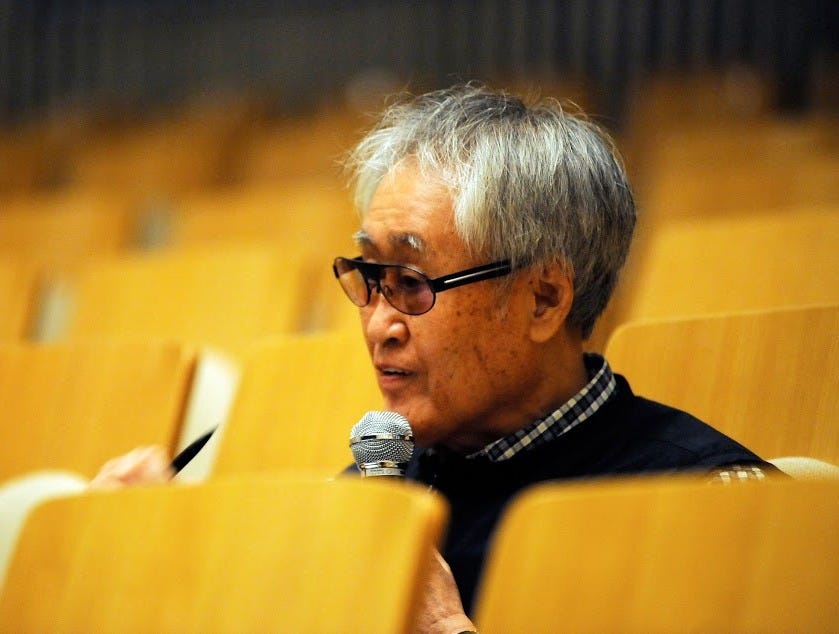

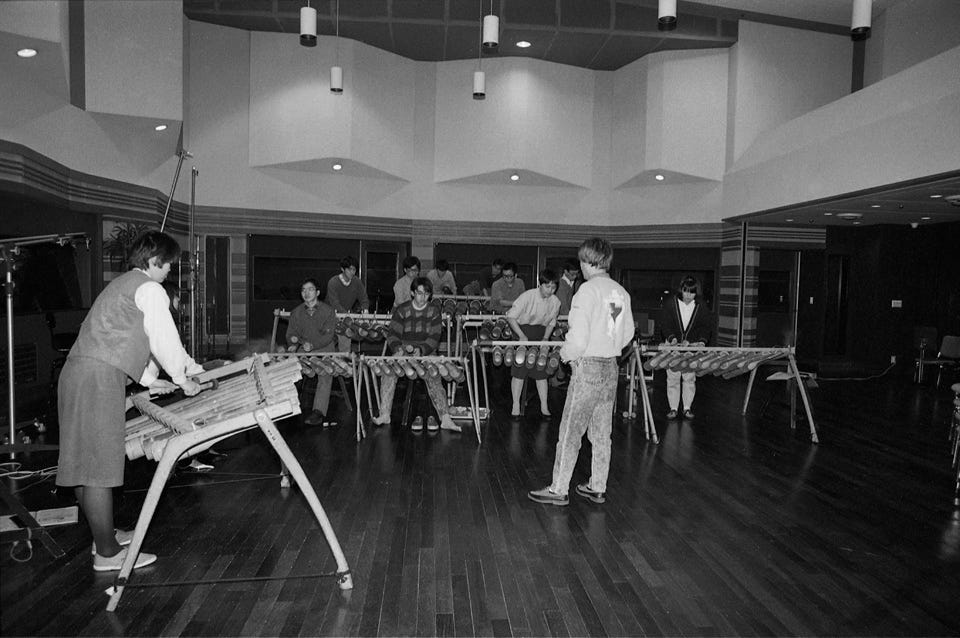

Shouji shiro was the composer and molecular biologist behind Geinoh Yamashirogumi, a shape-shifting group of self-styled musicians, ethnographers, anthropologists and computer scientists, formed in the 1960s to shake up the world of choral music with something of the same disruptive impetus that had animated the early practitioners of Butoh. Fascinated by the prospect of learning, mastering and synthesising the musical traditions of cultures from around the world, Geinoh Yamashirogumi could be found drawing on Bulgarian vocal patterns, Balinese kecak chants, or fashioning a kind of pan-Eastern spiritual music that found kinship between electronic instruments and folk traditions. In 1986, the group released Ecophony Rinne, a four-part suite that combined Tibetan percussion with Japanese Noh, Balinese gamelan and synthesisers. That Shouji Yamashiro took to the gamelan on Yas-Kaz’s invitation is perhaps no surprise. That it would come to define the sound of anime for a generation probably is.

Awash with money and with the prerogative to entertain the burgeoning middle classes, anime in the 1980s experienced what would become known as its golden age. Decades of experimentation with the form had culminated in an accumulation of knowledge, artistic technique and technological advancements which allowed animators and screen-writers greater freedom to push the boundaries of what was previously possible. Not constricted by generic expectations, production houses such as the now renowned Studio Ghibli were able to experiment liberally with both form and content. Provocative, adult themes were radical if also often disturbing expressions of this freedom, which brought a sensitivity for mood and atmosphere to an already developed feel for narrative. A boom in production was the result, and with it came the space for composers to be similarly adventurous.

Like the animators with whom they would work, it could be argued that the 1980s was also a golden age for electronic musicians. Knowledge and technical ability with synthesisers and drum machines developed over two decades of trial and experimentation meant that many musicians now felt comfortable bending their electronic instruments into new and exciting shapes. What would perhaps ten years earlier have appeared novel, was, in the hands of the likes of Yellow Magic Orchestra, becoming a flexible piece of musical vocabulary. Feed into this a desire to reach for the percussive, varied and highly refined instrumentation of non-Western musical traditions, and the basis of the new age music collected on this compilation comes into view.

Akira is widely acclaimed as the pinnacle of anime’s golden age. Set in a fictitious dystopian Tokyo that tapped into the latent dread and disquiet that bubbled beneath the veneer of ‘80s economic prosperity - a kind of neoliberal endgame brought on by the breakdown of the social contract - the film’s reputation transcended that of anime and brought with it new audiences from around the world.

It is often the sign of a good soundtrack if a film becomes indelibly tied to its sound. In the case of Akira, this was in part also because Geinoh Yamashirogumi were given free rein to compose the score before the work of illustration had even begun. Where the mood of the music led, the animation owed.

Employihe micro-tonal elements of gamelan tuning systems not then available on commercial synthesisers, the group re-programmed their instruments to seamlessly incorporate the acoustic and electronic elements of the score. On Kaneda, it’s the Balinese jegog - a gamelan of tuned bamboo played at breakneck speed - that takes centre stage. If Geinoh Yamashirogumi’s score helped to define the pacing and atmosphere of the whole film, much of that was down to the sonic characteristics of the gamelan.

In a sense then, Yas-Kaz’s innate curiosity for new percussive sounds played a pivotal role in the development of what became known as new age music in Japan. He represented a confluence of influences - a belief in the Japanese avant garde on the one hand and on the other a desire to reach out beyond its borders on the other. His track Hei (Theme of Shikioni), drawn from popular period sci-fi manga & anime series Peacock King - Spirit Warrior, spoke of this coming together.

Taking his name from a manga character, Kitaro’s blend of electro-acoustic instrumentation and Japanese Shinto-Buddhist spirituality is perhaps the most widely recognised exponent of Japanese new age music. And yet, like many of his contemporaries, Kitaro too found his break scoring for TV, on an NHK-produced documentary series about the Silk Road. Travel, commerce and cultural exchange all coalesced along the trade route, creating the conditions for a sound that drew from a number of musical traditions and could present itself as being similarly nomadic.

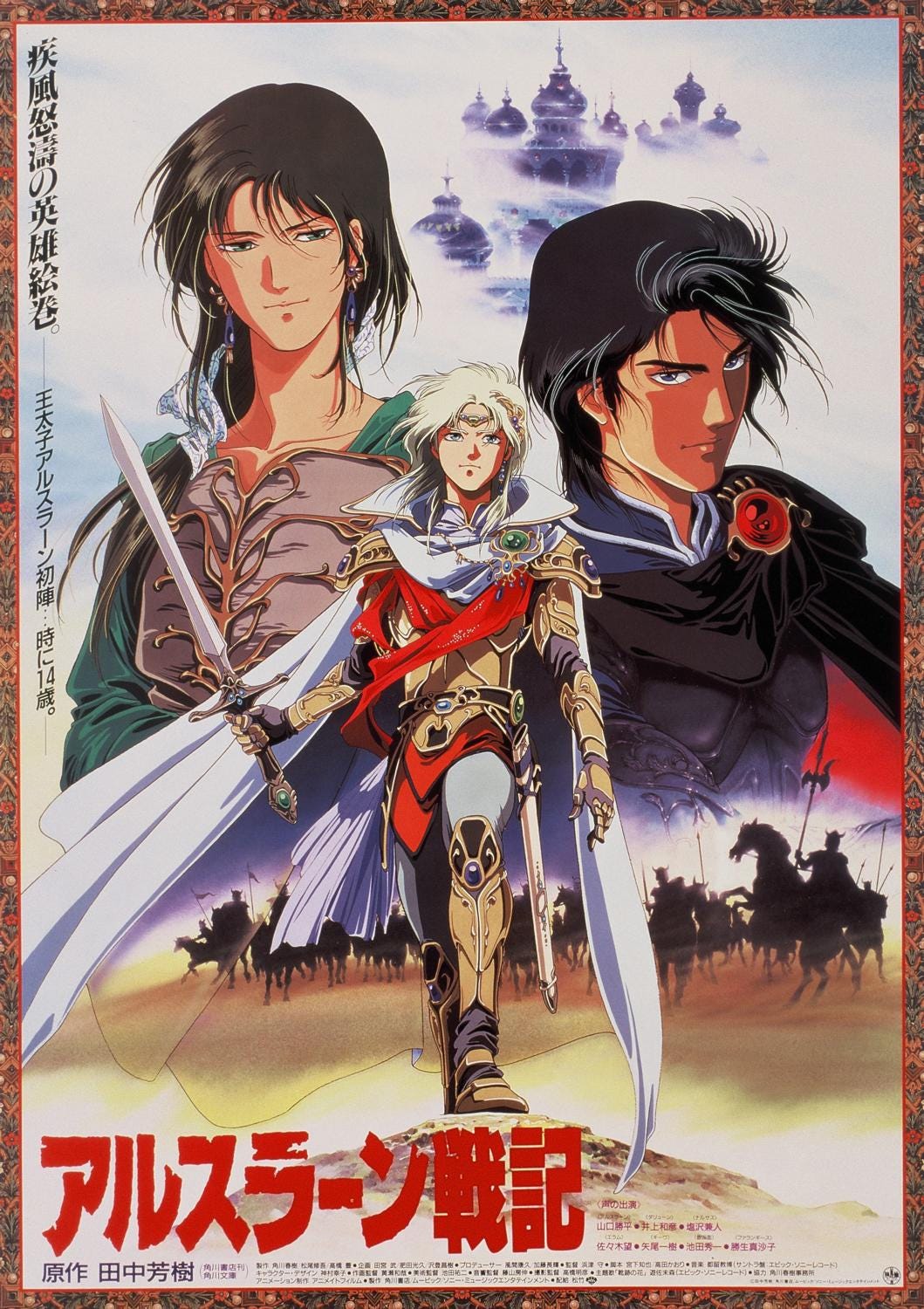

Like Kitaro’s Silk Road, it was often TV’s fascination to showcase distant lands and cultures that shaped the direction of the music. A violinist and composer, Norihiro Tsuru had recorded and toured with Kitaro throughout the 1980s before launching his own studio in 1987 to work on soundtracks for TV and animation. When Tsuru was hired to score the anime The Heroic Legend of Arslān, set in ancient Persia - and from which his track Farsighted Person is taken - it was the story which determined the sonic direction the music would take. Escapism, adventure and a conflation of the fantastical and the foreign were all ways in which the anime of the time built alternative worlds for its viewers, and in turn provided a fruitful, commercial relationship for the development of new age music.

Because if there was a tension at the heart of the economic boom that swept money and opportunity before it in Japan in the 1980s it was that between a country looking outwards for inspiration and inwards for itself. And as with the new age movement in the US and elsewhere, in Japan there existed an uneasy contradiction between the quest for spiritual enlightenment and the market value it was rapidly able to command. At its best this represented a genuine enthusiasm and respect for diverse musical traditions, and at its worst a neo-colonial flattening of cultural specificities, appropriated for aesthetic or profit.

In a sense, much of what has become understood as Japanese new age and revisited by reissue labels in recent years dovetailed seamlessly with commercial concerns. The environmental music of Kankyō Ongaku, devised for architectural spaces and advertising campaigns, made nonchalant bedfellows of sound and marketing, exploiting big budgets and relative creative freedom to produce a fascinating, intuitively organic counterpoint to the ambient music of Brian Eno and his contemporaries. At the other end of the spectrum was something a little more earthy, something which sought less of a designed experience and one which reflected the burgeoning environmental movement that was also a cornerstone of the new age sensibility.

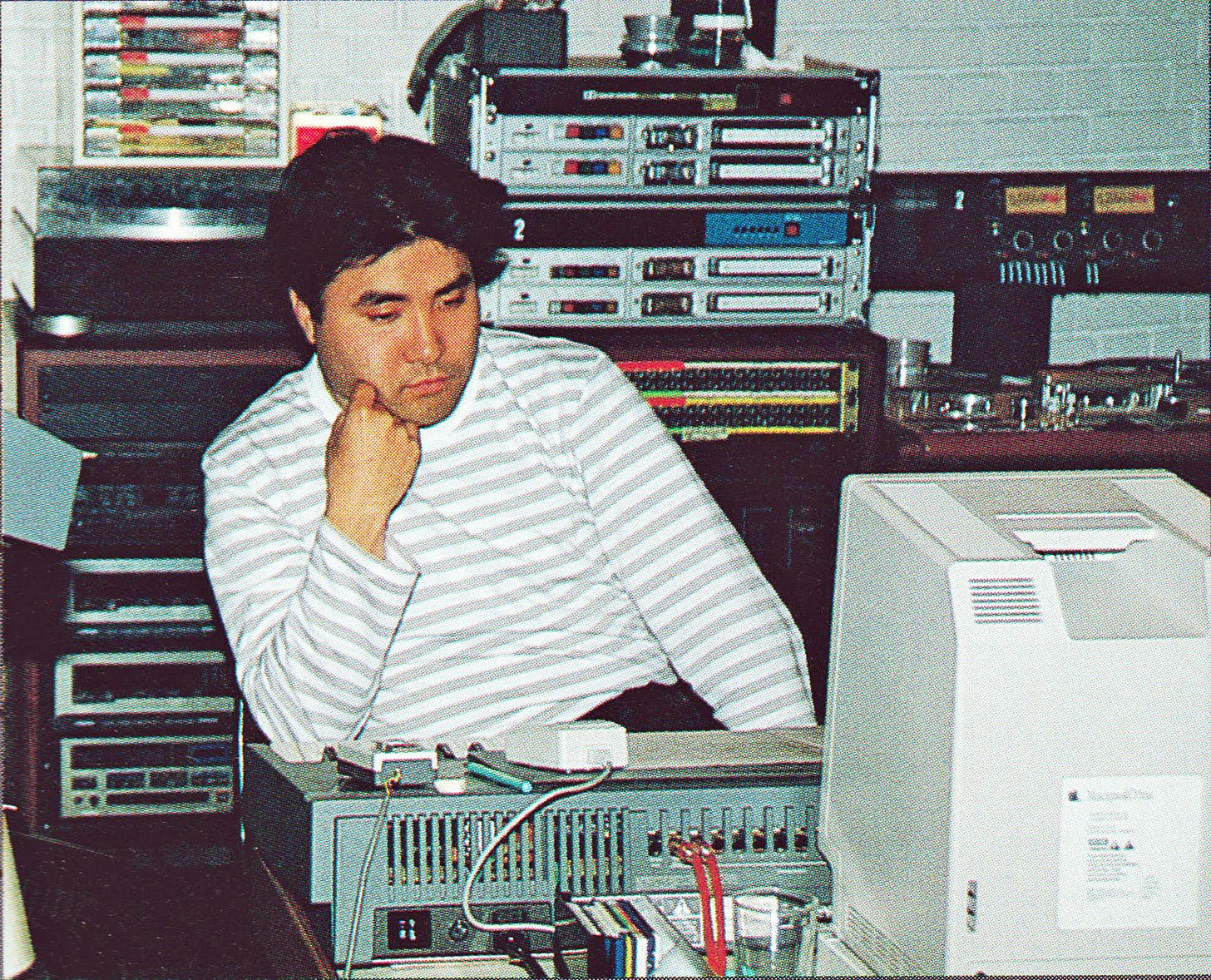

Pianist and percussionist Yoichiro Yoshikawa was another who benefitted from the tutelage of Yas-Kaz. Also finding his way into the scene via Butoh company Sankai Juku, Yoshikawa spent his time hanging out in Roppongi in downtown Tokyo, obsessed with the new wave of electronic instruments like the Fairlight CMI, Prophet 5, Roland TR-808 and Linndrum LM-1. Taking on jobs at Kabuki theatres and listening voraciously to the fourth world of Zero Set, Jon Hassell and Eno and Byrne’s My Life In the Bush Of Ghosts, Yoshikawa came to Yas-Kaz for percussive instruction, drawing a range of textures into his already unique sound.

Picked up by Alfa Records - the independent label responsible for releasing YMO and much of the era’s best city pop - Yoshikawa cut demos that landed him a job scoring a new series for NHK, called The Miracle Planet. Comprised of twelve one-hour episodes to chart the different months of the year, the series was a kind of proto-Planet Earth - a broad-strokes panegyric for the conservation and protection of the Earth’s endangered ecosystems. Both of Yoshikawa’s two tracks featured on this compilation, Tassili N’Ajjer and Fiesta Del Fuego, are taken from his soundtrack.

Such was the appetite for entertainment, soundtracks were sometimes commissioned from groups assembled solely for specific projects, about whom little was written. One such group was the Columbia Orchestra. While it shares its name with an in-house group for the Nippon Columbia label in the 1960s, it's likely that on Hearts Beats - Theme for Andrew Glasgow, the name was more of a place-holder. With shades of MKWAJU Ensemble, Reichian counterpoint and expansive jazz fusion, the intricately realised percussive track might be seen as a piece of image album library music - the only track on this compilation to accompany a static manga - and yet one which collected some of the most adept session musicians in Tokyo at the time.

In an interview to mark his 90th birthday, the late composer behind this compilation’s first track, Chumei Watanabe, articulated just what it was that made scoring for anime so appealing. “Songs for animations can be made with more verve and more freely than songs for adult dramas,” he said. “I kept in mind that I would not compose childish music even if the target of the dramas was children.” An influential figure who scored many of the most popular children’s anime and TV series, Watanabe’s punchy pentatonic melodies with tight jazz funk arrangements helped define the sound of childhood for many. Written for kids TV program Space Sheriff Shaider, Fushigi Song was used to reference the villain’s lair, bringing a playfulness to bear on what was otherwise a trippy and infectious groove that has some sonic similarities to Don Cherry’s Brown Rice.

At the other end of the compilation, and its final track, Gishin Anki was composed and performed by Kan Ogasawara, whose track Honowo opened Time Capsule’s previous anime soundtrack compilation. A lawyer turned self-taught composer, Ogasawara’s interest in synthesisers and electronic equipment had made him an invaluable session player, but it was under his own name that he would go on to release nine albums in the 1980s. Taken from the same soundtrack as Honowo, Gishin Anki illustrates just how broad a palette of interpretations and musical styles this fascination with percussive traditions could usher forth. Showcasing Ogasawara’s ear for the dramatic, it brings the compilation to a close with a flourish.

Anton Spice & Kay Suzuki

Purchase ‘TV, Anime & Manga New Age Soundtracks 1984-1983’ here

Become a paid subscriber to unlock this month’s Bandcamp discount code 👇

👇 Use this code at checkout to get 15% off your any order this month:

➡️ sub_april_2025

https://timecapsulespace.bandcamp.com/